Unmooring

I found out I was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder a year ago, when I was 25, from an offhand comment my psychiatrist made. The way she dropped my diagnosis in conversation made it seem like it was obvious or as if I already knew or should have. But no one had ever named my experience before. Similarly, when I was in college, a lady from Georgia with a soft southern accent who worked in the student health center prescribed me medications, but I was never told what for—I wondered if I even had a diagnosis. The pills I was prescribed included some I’d heard of, like Ativan, and ones new to me like gabapentin and Lamictal. When I sought treatment again this past year, the doctor asked me to rate my mood on a scale of one to ten, and I could only tell her, “I cannot crawl out of my sadness.” I could not numerically quantify the thing that was eating me, could not understand it—I only knew I was being subsumed by something.

Jane Kenyon writes in her poem “Having It Out with Melancholy” about feeling melancholy ever since she was a little girl, a sad baby who couldn’t even be saved by “the yellow / wooden beads that slid and spun / along a spindle on [her] crib.” “I was already yours,” she writes, “the anti-urge, / the mutilator of souls.” One of the most famous lines of the poem is: “Unholy ghost, / you are certain to come again.” She goes on to write, “There is nothing I can do / against your coming. / When I awake, I am still with thee.” Frighteningly, like the Holy Ghost, melancholy inhabited Kenyon, insidious, its vengeance to consume eternal. I first read the poem in college but forgot the writer and title, for years only remembering someone else’s words describing my own experience—the feeling of something alien inhabiting my body and tugging me under. Discovering the poem again years later felt like a comforting relief.

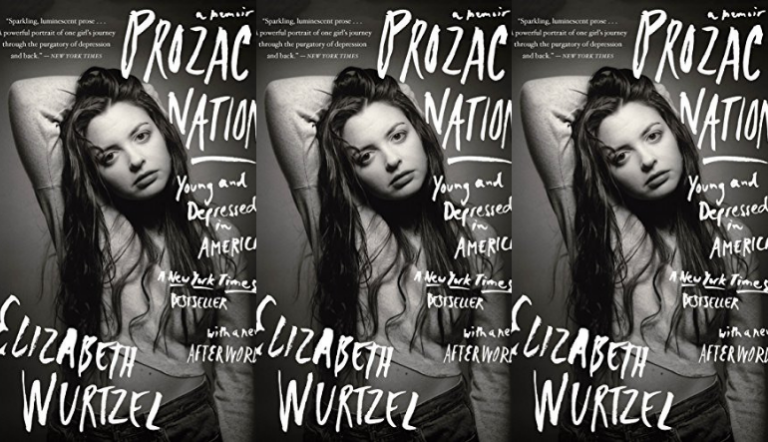

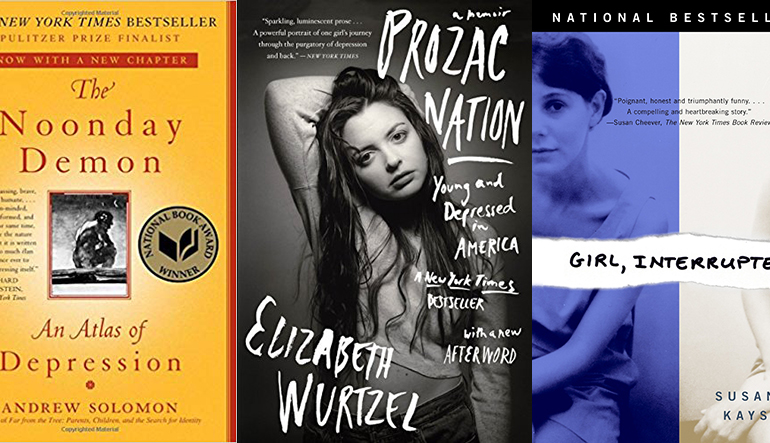

Like Kenyon, those who write about their mental illnesses—Susanna Kaysen, Andrew Solomon, Kay Redfield Jamison, and Elizabeth Wurtzel to name a very small few—often struggle to reconcile their character with the disease that riddles them. In An Unquiet Mind, Jamison says of her manic-depressive illness (formally known as bipolar disorder, although Jamison uses the term manic-depressive because she feels it more accurately represents the severity of her illness): “my illness seemed at first simply to be an extension of myself—that is to say, of my ordinary changeable moods, energies, and enthusiasm.” I, too, have doubted that my illness differs from my character, struggled with how to see what feels normal to me as abnormal given the intensity of the highs and lows, and, like Jamison, my refusal to accept that I have a mental illness has prompted me to resist medication and proven perilous at times.

Kaysen, who was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and was committed to the famous McLean Hospital, writes in her canonical memoir Girl, Interrupted: “I had a character disorder. Sometimes they called it a personality disorder…I imagined my character as a plate or a shirt that had been manufactured incorrectly and was therefore useless.” Terrifyingly, Kaysen points out that one’s very self is compromised when one becomes mentally ill. One is unmoored from the self they thought was them. More bluntly, Wurtzel states in Prozac Nation: “I feel like a defective model, like I came off the assembly line flat-out fucked and my parents should have taken me back for repairs before the warranty ran out.” That line stuck with me as a truth I felt too.

In his book The Noonday Demon, Solomon notes that “depression cannot be separated from the person it affects. Treatment does not alleviate a disruption of identity, bringing you back to some kind of normality; it readjusts a multifarious identity, changing in some small degree who you are.” In other words, the self is mercurial, precarious, unfixed. Illness can—and does—take the self over, changing it, forcing the mentally ill to reconsider their very character often in a frightening, traumatizing way. “Which of my feelings are real? Which of the me’s is me?” Jamison asks. “The wild, impulsive, chaotic, energetic, and crazy one? Or the shy, withdrawn, desperate, suicidal, doomed, and tired one? Probably a bit of both, hopefully much that is neither.”

Illness and self are intertwined in such a way that medication does not necessarily eclipse one’s self but neither can it draw out an essential self either. When one is mentally ill, one begins to wonder where the illness stops and the self begins, if the two can even be parsed. They cannot, Solomon asserts. “There is no essential self that lies pure as a vein of gold under the chaos of experience and chemistry,” he writes.

I once thought my manic behavior was an innate, and therefore normal, part of my character, and maybe it is, but that doesn’t mean it’s not without consequences. I thought I was just the sort of person whose thoughts sometimes catapulted them out of bed in the morning straight into a day-long project during which I forgot to eat. I thought I was just the sort of person who could laugh and dance with giddiness in the morning—that was just being hyper, wasn’t it?—and then crash into gloom not an hour later. I was just moody, although I only let the good moods show in public. In other words, separating out illness from character forces me to reckon with qualities I once considered parts of myself as manifestations of illness instead. “People say, when I complain of being less lively, less energetic, less high-spirited,” Jamison writes, “‘Well, now you’re just like the rest of us,’ meaning among other things, to be reassuring. But I compare myself with my former self, not with others.”

Then there comes the necessity of seeking medication, which can feel like a colossal admittance of weakness, a decision that begets shame. “The constant presence of the medications is for me a reminder of frailty and imperfection,” Solomon admits, “and I am a perfectionist and would prefer to have things inviolate out of the hand of God.” Jamison feels similarly and battled at length with adhering to taking lithium. “Why was I so unwilling?” she asks. “Why did it take having to go through more episodes of mania, followed by long suicidal depressions, before I would take lithium in a medically sensible way?” But after she starts taking lithium, she also laments, even as she sees what good the medicine does her, “I had a horrible sense of loss for who I had been and where I had been.”

I take my chalky white pills of Lamictal every day and now lithium, gabapentin and Ativan, Zyprexa and Risperdal as needed. My psychiatrist and I talk of managing my medications, experimenting with new drugs until we reach the perfect cocktail that will keep me, if not happy, stable. “I believe only in this moment / of well-being,” Kenyon writes of managing her own illness with medication. And like Kenyon, despite all of the pills, the unholy ghost still haunts, dormant not banished. Like allergies or migraines, this illness will always attend me, unshakeable, a thing I must manage. I know in moments of respite that this unholy ghost will come back, casually yet cruelly, pushy and dangerous in a way that makes me feel robbed of the agency to turn it away. My careful attempts to banish it feel, dishearteningly, fruitless. “There is nothing I can do / against your coming,” Kenyon says, and I’ve begun to think that this is true of me too. Although the illness may be dormant sometimes, it’s inside of me always, a part of me that will never go away no matter how diligently I try to exorcize it.

Letting my illness corrode me from the inside felt, for a long time, easier than speaking up about it. I’m not sure whether I kept silent out of shame; if it was out of shame, I’m not sure if I was ashamed of being privileged but being depressed anyway or if I was ashamed simply because I am mentally ill and unable to manage my moods successfully, at least at this point in my life, without medication. Do I feel a stigma? Probably. Do I feel alone in my illness? Often times, although I read loads of books about characters and people who deal with mental illnesses too.

I feel a certain kinship in particular with Anna Karenina. “How strange you are today!” Dolly exclaims while Anna is visiting her in an attempt to bring about a reconciliation between Dolly and her husband, Anna’s brother. “Do you think so?” Anna responds. “I’m not strange, but I’m depressed. I am like that sometimes. I keep feeling as if I could cry. It’s very stupid, but it will pass.” Like Anna, my depression feels stupid, and like her, I have enough self-awareness to know it will pass. Dolly and Anna don’t talk about her moods again, even when Dolly sees how precariously close to the ledge Anna is coming. And then it is too late. Anna and Dolly’s friendship is a cautionary tale of what happens when one stays silent about their mental illness and tries to hide it behind the trappings of a mostly perfect life. It is a cautionary tale, too, about what happens when one refrains from intervening in the life of a clearly sick friend.

Eventually, as Anna knows, if it does not kill you, the depression abates and there are moments that glimmer with hopefulness and beauty, relief and the ability to enjoy life again without complication. Kenyon wakes early and waits “greedily for the first / note of the wood thrush.” When she hears “the wild, complex song / of the bird…[she is] overcome / / by ordinary contentment.” This feeling’s lack of drama and its steady sureness prompts her to ask, “What hurt me so terribly / all my life until this moment?”

I wonder, too, about my own life, what has hurt me so terribly until this moment. The half a decade I spent seeking treatment for symptoms without realizing or being told that they clustered into a diagnosis buffered me from the blow of having a lifelong mental illness. I wonder why this illness has manifested in me, how to make sense of my self now that I can no longer deny that I have bipolar disorder. Be here now, I loop over and over in my head, trying to ground this brain and body of mine in the here and now, to push aside my anxiety and my fear of future manias and depressions, to rid myself of the shame I feel for needing to take medication in order to preserve my life. I try to share my experience, lest I become like Anna, another life cut short. I’ve guarded this illness so fiercely because of the shame and hurt and terror it has made me feel, and I try to make peace with this illness, to find a core self I can hold on to and not let go.