Sculpting Flesh From Text in My Body is a Book of Rules

What the hell’s a body, anyway?

What the hell’s a body, anyway?

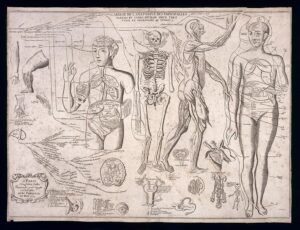

Sentient sack of meat. Brain holster. Recently, I tried to come up with another usable term and jokingly settled on “flesh carriage.” I tweeted this and people replied with their own suggestions, including “organ condoms,” “bone dressings,” “skeleton blankets,” and “trauma piñatas.” Made of lumpy guts and innards, bodies are the epitome of the weirdly, unknowably physical. Author Elissa Washuta (who came up with her own body alternative in this Twitter conversation, “sad sac of viscera”), writes about the tangible, fleshy self. In her memoir, My Body is a Book of Rules, we find her wedged between the pages, embedded in IM conversations, footnotes, and numbered lists; she’s stories lodged within stories, her body forcefully stretching the margins. Washuta utilizes spacing, italics, font shifts, and non-linear narrative patterns to give the work heft. It is a visual, wildly dynamic record; a memoir that transforms the paper it’s printed on into flesh and bone.

How to control the body is a constant theme in Washuta’s work. Her memoir opens with a look at how female Catholic saints informed her early sexual self, an expectation of chastity or death. Two books shaped her physical identity: the Bible and Cosmopolitan. She arranges narratives from each in columns, one side providing “commandments” and the other previewing a magazine-style Q&A. In a section titled, “QUESTIONS FROM COSMO THAT SEEMED IMPORTANT WHEN I WAS TWELVE, EIGHT YEARS BEFORE I LOST MY VIRGINITY,” her Catholic school upbringing mirrors a variety of sex tips. Her knowledge of sex in this repressive religious context produces bodily confusion:

We were supposed to cross our legs, clamp them shut with steel; we were supposed to guard our chastity with our lives. My body was a book of rules, my heart the spine, my skin plastered with pages. Written on each one was the text that held the world together.

This rendering of the text-as-body is dynamic, fluctuating along a sliding sexual spectrum. Our eyes dart between the columns, absorbing information the same way Washuta once did. Her bodily confusion, based on competing sexual educations, becomes a real, experienced thing. It is palpable. When she remembers her Catholic school upbringing, we are there alongside her as she also remembers her Cosmo commandments.

This confusion works throughout the memoir to underline personal history. How we experience memories is slivered and unexpected. They slide inside these essays, painful burrs that cling to the text. References to earlier pieces pop up in private conversations later in the book, tucked inside diary entries and lists. The memoir forces readers to continuously engage with Washuta’s personal history, to remember it privately and publicly. This creates movement, charging us to look ahead and then look back, to check footnotes and asides, to reconsider what we thought we knew. In “Faster Than Your Heart Can Beat,” we read from a numbered list of sexual partners, counting backward in time. Washuta considers her physical self in conjunction with those other bodies, but also with regard to location, age, where she was mentally, and her level of considered “experience”:

In the month before my move, I separate proper adult clothes from ho gear and put the latter in boxes in the attic. Now I am an adult. I take Klonopin every night to sleep. Soon I will shed my old life like a cicada’s brittle shell.

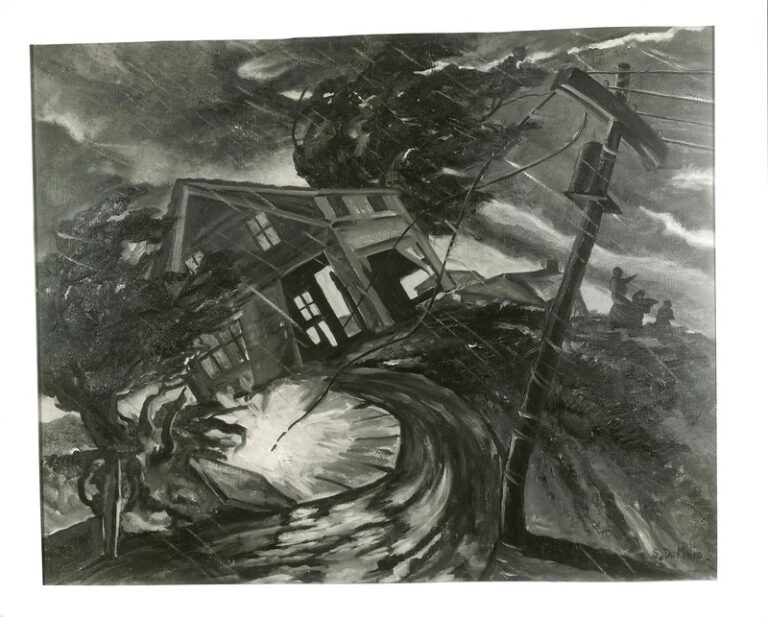

In “Actually–” there’s more framing of the body-as-text. The essay includes a history of assault, closely diagramming personal trauma. Settled close to the heart of the memoir, this work informs earlier essays in the book and provides the most physical, graphic arrangement of text. It’s subject matter that’s difficult to frame and even harder to write about. Fonts change. Margins widen and retract. Items are italicized or given bold text. Snippets of creative writing completed at the time of the assault are included, work that shows what happened to Washuta internally. Externally, the embedded histories provide skeletal structure; a backdrop to a bruising narrative. Throughout the essay, conversations from the day of the trauma run along the bottom of the page. In an IM chat with a close friend, she discusses what occurred during the assault. As the piece unfolds, this conversation lengthens, stretching upward, pushing the present into the margins. As the essay concludes, footnotes have taken up all the space on the page. It is powerful and very physical, a significant moment of taking back control.

Washuta also unpacks the body through discussions about her mental illness. In “Prescribing Information,” she details her experiences with various prescriptions. The side effects are listed like one might hear in a TV commercial. In a section titled “2/23/07 CETRIZINE (ZYRTEC) 10MG,” memories of previous drugs are inset through italicized religious text, reminding readers of the religious body presented at the beginning of the memoir:

Naked I came out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: the LAMICTAL gave, and the LAMICTAL hath taken away; blessed be the name of the LAMICTAL.

The margins are wide, providing stark contrast between the print and whiteness on the page. Further examining bodied space, Washuta writes about pop culture, forcing us to reconsider what constitutes storytelling and personal history. She provides snippets of actual television dialogue (Law & Order: SVU paired neatly alongside her own trauma narrative, a wildly impressive way to reassess personal growth through an inset narrative) and references to celebrities who’ve dealt with mental illness and bipolar disorder (Kurt Cobain and Britney Spears are contemporaries in the narrative, successfully skewing notions of how the brain processes linearity). The body, something misunderstood and vulnerable, presents as something that wants to continuously question and rediscover itself. Washuta attempts to unravel community and family with these essays, specifically how her body fits inside and outside personal history. The momentum she creates compels us to look along with her.

Okay, so how do we write about a “sad sac of viscera”? When we write about our physical selves, we’re attempting to transpose text into something substantive. We want to understand how our bodies work: how we feel, why we love. Throughout her memoir, Washuta does this investigative work by unpacking herself. She collects the pieces of her personal history and gracefully Frankensteins them together again, creating a narrative that moves freely on the page. She lives in the margins and inside body paragraphs, jumping out at us with words that are bold and also BOLD, italicized, capitalized. She finds footholds in footnotes. What grows out of her text is a wholly live thing, a body that walks and talks, that shrinks and grows, that hurts, that sings out. It is supremely physical. It is the body she controls. It is a self that is entirely her own.