Serial, Timelines, and Fiction

In “Route Talk,” an episode from the first season of Serial, Sarah Koenig and her producer attempt to recreate the state’s timeline of the murder of Hae Min Lee. As I listened to them test what was possible, I was struck by how similar their exercise was to one creative writers perform.

Whenever I move a scene, I have to rearrange the novel’s timeline. If I want a character to be a certain age at the time of a historical event, I have to live with (and keep track of) that birth year. It’s a painfully obvious point, but it can be an inconvenience for other aspects of the story. If I want people to go on vacation at a certain time, because it makes sense for the narrative, that needs to happen at a time of year when those characters would actually take a vacation. I am constantly squaring things up, and I misplace weeks and days with alarming frequency.

Writers have handled the problem of the timeline in many different ways. Joseph Heller handwrote a stunningly detailed outline of Catch-22, complete with a timeline. (It’s worth zooming in.) As freewheeling as Catch-22 seems, Heller kept careful track of details like the number of missions Yossarian had flown as the book progressed. I’ve tried index cards, lists, and spreadsheets, but I finally grew tired of tabulating ages and hunted for software. Aeon Timeline has proved useful, not just for tracking the timeline of the story, but also for developing backstory. Aeon will tell me each character’s age at any point in the story. It also knows the days of the week for every year on record. It has many more features, but the simple ones do it for me. Aeon was developed for writers, but it’s also marketed to lawyers.

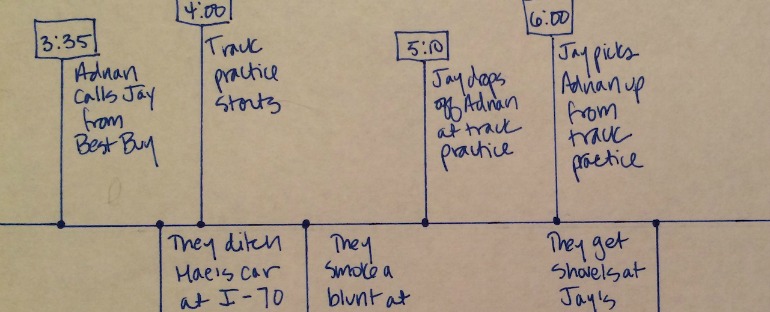

A major detail of “Route Talk” is a detour that Jay Wilds, the state’s key witness, claims he and Adnan Syed (the high school student convicted of Hae’s murder) took on the day Hae was killed. Jay says that after Adnan killed her, after he called Jay to pick him up and showed him Hae’s body in the trunk of her car, after they ditched her car, they drove about twenty minutes out of their way to Patapsco Valley State Park to smoke a blunt. They did this although it would have been important for Adnan to arrive at track practice when it started, at 4:00 p.m., so he would have an alibi.

As they drive to the park, Koenig says:

This just seems absurd . . . it’s between 3:45 and 3:50 now, in their world, and if I’m Adnan and I need to be seen for track I’m freaking out right now that I need to get back for track to have an alibi, so what’s this like, ‘Oh, let’s just drive halfway across the county to go to a state park to smoke a blunt?’ Like, just smoke in your car. I don’t know. It just seems like there had to be other places you could have just pulled over for a quick smoke.

In his police interviews, Jay paints a picture of the scene, complete with an important talk about the murder and a discussion of where Adnan might dispose of Hae’s body. The trip to Patapsco appeared in two police interviews with Jay but was dropped from his testimony at trial. The conversation is still in the trial testimony, but it takes place in Adnan’s car at a different time.

Koenig is baffled. “This is a puzzle to me. It’s such a vivid scene Jay’s describing. It’s so detailed. I have to think he included it for a good reason. But it doesn’t fit the timeline.”

I know this is real life. I know a real person was murdered. For me (and plenty of others), part of the tension of listening to the podcast was trying to balance my sense of decency with my hunger for the story. And still I can’t help thinking that Koenig’s comment about the scene could easily be a comment from a fiction workshop. It’s a good scene but it’s in the wrong place. Can you put it somewhere else? A large part of the intrigue of the podcast is exploring the holes in the various witness’s timelines, finding the things that don’t make sense.

Any early novel draft has plenty of plot holes, plenty of things that don’t make sense. Some of these things have to do with time and place. Software and fact checking and charts can help with that. But some of the things that don’t make sense have to do with the writer making characters do things they simply wouldn’t do. The Patapsco story is a mix of both.

At Patapsco Valley State Park, Koenig tries to come up with an analogy for “the uselessness of what we’re trying to do by recreating something that doesn’t fit. . . . It’s like trying to plot the coordinates of someone’s dream or something.”

I still don’t have an opinion about whether Adnan Syed murdered Hae Min Lee. I do know that the Patapsco iteration of Jay Wild’s story doesn’t work. A jury that feels as though it’s trying to plot the coordinates of someone’s dream is likely to acquit, and I suspect that’s why the story changed.

In The Art of Fiction, John Gardner describes a very different kind of dream—“the vivid and continuous fictional dream.”

In bad or unsatisfying fiction, this fictional dream is interrupted from time to time by some mistake or conscious ploy on the part of the artist. We are abruptly snapped out of the dream, forced to think of the writer or the writing.

That’s what happens when Jay’s timeline goes off course. For writers, the timeline is often a housekeeping task, but it’s an indispensable part of the vivid and continuous fictional dream.