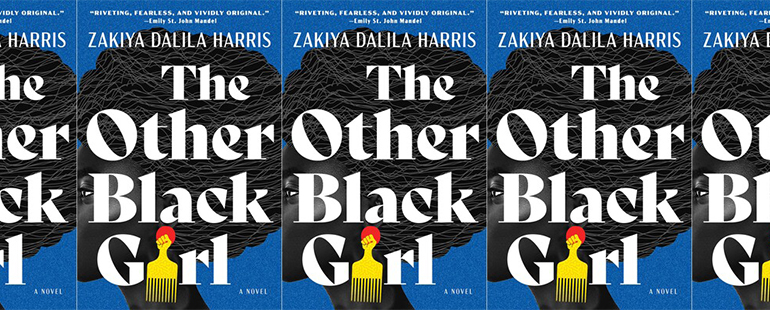

Skewering Workplace Racism in The Other Black Girl

The Other Black Girl

Zakiya Harris

Atria Books | June 1st, 2021

In Zakiya Dalila Harris’s debut novel, The Other Black Girl, Nella Rogers is a young black editorial assistant at Wagner Books, an esteemed publishing company in New York City with a penchant for only hiring “Very Specific People who came from a Very Specific Box”—the majority of Wagner’s staff is white, middle class, and blissfully ignorant about race. Nella, the only black girl in the office, has to straddle two cultures and mute her blackness at work just enough to be accepted. As her best friend, Malaika, says to her, “You broke in all those white people at Wagner. You’ve been preparing them not to say dumb shit in meeting for two whole years.” Nella had to “break in” her white coworkers to protect herself from their microaggressions, and from their persistence in being color blind. This is the duality of black life in America—teaching white people how not to be racist while experiencing their racism.

The Other Black Girl is about many things—friendship, the humdrum office culture—but its driving pulse is a sharp critique of the publishing industry’s lack of diversity. Wagner Books is a microcosm of the industry: according to a survey conducted by Lee & Low Books on diversity in the publishing industry released in January 2020, “seventy-six percent of publishing staff, review journal staff, and literary agents are White.” Harris, who worked in publishing before writing this novel, is telling the industry to pull down their blinders.

In the novel, we see firsthand the industry’s uniformity and its harrowing effects on nonwhite staff. Harris’s prose creates a deep realism, allowing readers to experience Nella’s loneliness and isolation at her job. Nella’s cubicle and a bathroom stall become refuges from which she can combat her office’s cultural deprivation and microscopic acts of racism. “Her colleagues, strangely, had made it clear very early on that they didn’t really see her as a young Black woman, but as a young woman who just happened to be Black. As though her college degree had washed all of her melanin away.” This moment feels as if it could have been copied and pasted from Harris’s real life. It also captures a duality of black life—invisible yet hypervisible. “In their eyes, she was the exception, She was ‘qualified.’ An Obama of publishing, so to speak.” This racial binary leaves Nella stuck in a betwixt state, and it allows her white colleagues to maintain their ignorance.

Soon after Nella is hired, diversity, equity, and inclusion become the new buzzwords at Wagner Books, a reflection of conversations taking place outside of the publishing industry. At Wagner, race is “the major elephant in the room,” and when Nella attempts to spearhead the conversation about it during a mandatory Diversity Town Hall meeting, the discussion becomes a screwball comedy:

When Nella offered up the acronym ‘BIPOC’ as a term she associated with ‘diversity’, her coworkers ooh-yeahed . . . and then offered their own examples of ‘diversity’: ‘left-handedness,’ ‘nearsightedness,’ and ‘dyslexia.’ Only when someone volunteered the word ‘non-millennial’ did Nella realize that a return to her own concern about the treatment of Black people both inside and outside of the literary sphere would be highly unlikely.

Nella’s white colleagues fail to see issues beyond the scope of their experience, and, as a result, steal the conversation to highlight their own insufficiencies. Their whiteness has to be center stage. Too, this scene recalls the “All Lives Matter” rhetoric in a funny and poignant way. The best satire reveals the skeletons in our closets and guides us to a deeper sense of truth. This is where the book thrives: Harris strategically inserts satire during moments in which characters demonstrate unconscious bias, allowing us to see the nuances of racism. Harris forces us to dwell in these uncomfortable, awkward moments; they linger even after the book has ended.

The toll of trying to teach her colleagues how present racism is weighs on Nella. “She craved the ability to walk across the hallway, vomit out of her feelings about a racially insensitive fictional character, and return to her desk, good as new.” She wants to be fully seen and validated without having to explain black culture and racism to her glib coworkers. When Hazel, “the other black girl,” starts working at Wagner Books, Nella is therefore—at first—overcome with joy. She believes that they will be “two soldiers in the trenches,” fighting the good fight together. But Hazel’s intentions are different—she wants to move ahead in the company and will take down anyone in her path, including Nella. When Nella receives a malicious note—“LEAVE WAGNER. NOW”—her last sense of trust and belonging is shattered.

“Nella exhaled as she slid the note back into the envelope, intent on throwing the entire parcel into the recycling bin and forgetting she’d ever read it,” Harris writes. “But something stopped her—the cathartic desire to share its existence with someone else, and the inherent need to survive.” In the end, what saves Nella is her resistance, friendships, and determination to live beyond the measure of racism. In The Other Black Girl, Harris creates a space for black writers and writers of color to tell their own stories in their own way. She’s following Toni Morrison’s mantra: “I stood at the border, stood at the edge, and claimed it as central. I claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.” Harris imagines a world where being the only black girl agent, writer, book editor, and editorial assistant is a thing of the past.