SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE Revisited

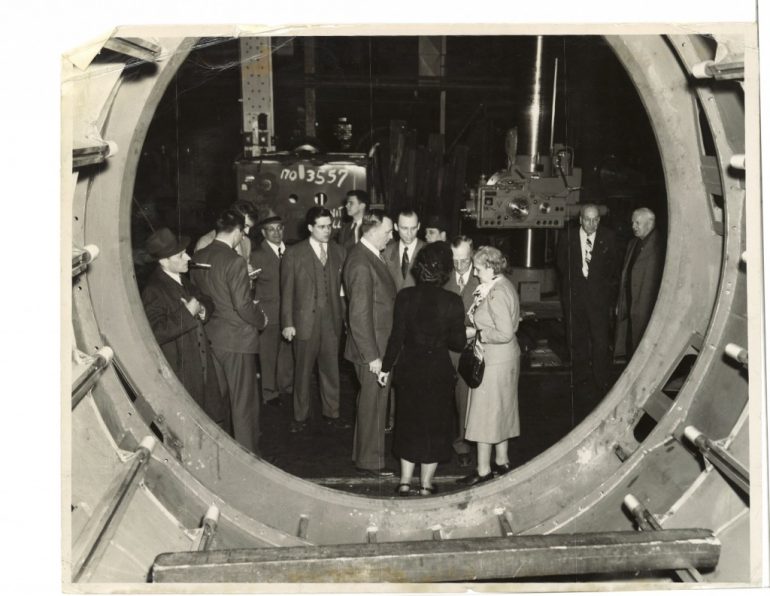

Image: Vonnegut, third from the left, takes notes during a VIP tour of the General Electric Plant in Schenectady, New York. (Mary Robinson)

By way of introduction at readings, I often start with a poem about my hometown. “For those of you who don’t know me,” I say as preamble with an affected stand-up-comedy-like cadence, “I’m from Schenectady, New York, and I think it is the greatest small city in the world.” I wait a beat before the punchline: “But, I might be the only one.”

For decades now, my hometown has been embattled. As industrial jobs were sent to colonial (I mean: global) elsewhere, Schenectady withered on the proverbial vine. A third of the city’s population has defected since 1950; more than a quarter of residents live below the poverty line; eighty percent of public school students receive free or reduced lunch; and when I was finishing high school, we got slammed with a Ba3 credit rating—the worst in the state and one of the most abysmal in the country. Union College, the liberal arts institution that has anchored downtown since 1795, routed prospective students six miles out of their way so as not to see the city streets that the New York Times stingingly called “a symbol of urban decay.”

Despite its paucity, Schenectady has a hold over many of us who have called it home: the backwater colonial outpost that became—all too briefly—the city that lights the world. Its old ethnic neighborhoods are new ethnic neighborhoods; its people still bare-knuckled as winter sets in.

The ornery love we’ve been harboring for Schenectady makes everyone else’s opinions on our well-patinaed city more intolerable. Near neighbors are shade-throwing unbelievers. “Hating on Schenectady” appears as number twenty-five on BuzzFeed’s listicle “49 Things People From Upstate New York Love.” Further-flung interlocutors are worse still. People stare blankly while I enunciate slowly the four syllables of our long-displaced indigeneity: Ska-neck-ta-dee. (Though, I will say there were a few years around 2010 when I got a lot of, “Oh, I saw that movie with Phillip Seymour Hoffman.” Believe me, reader, when I tell you this did not alleviate my long suffering.)

So imagine my relief as a teenager when I stumbled into Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, his “book about Dresden,” and realized he knew what I knew. In the novel’s first chapter, a bald-speaking, penitential Vonnegut, reveals that when he returned from World War II’s unspeakable barbarisms, he arrived to Schenectady, New York. At the recommendation of his brother, he became “a public relations man” for General Electric and a volunteer firefighter. “World War Two had certainly made everybody very tough,” he wrote of those he came to know in the scrawny years between 1947 and 1950. It was those years Vonnegut was writing the War Department asking politely and desperately for details of the Dresden firebombing which he had witnessed as a prisoner of war, only to be told they were “top secret still.” “The nicest veterans in Schenectady, I thought,” Vonnegut nearly sighs in the same breath, “the kindest and funniest ones, the ones who hated war the most, were the ones who’d really fought.”

In what follows, Vonnegut cedes his voice to his time-traveling protagonist, Billy Pilgirm. Pilgrim shares much of Vonnegut’s wartime biography—a prisoner of war who survives the firebombing in Dresden because he’s held in the meat locker of the eponymous slaughterhouse 5. But unlike, Vonnegut, Pilgrim is an optometrist who can’t quite look the thing straight on. Instead, the novel, by virtue of alien abduction and formal innovation, sifts back and forth through a lifetime just to approximate the unnerving complexities of a single, needless, violent day.

*

This winter I found myself in Dresden, “the loveliest city that most of the Americans had ever seen,” as Vonnegut wrote. Having only been to Indianapolis, the young author thought it looked like Oz. I ignored recommendations for art exhibits in Neustadt, and took a pass on the opportunity to eat German-styled small plates out of mason jars. Instead, I walked in forecasted drizzle, “crossed the steel spaghetti of the railroad yard,” and arrived to the outskirts of town. I felt as if I was slipping through a tunnel from my hometown to the other side of the world. Reading Slaughterhouse-Five, I realized, was my first consciousness, my first glimpse of Dresden.

The slaughterhouse still stands, and even boasts a warm weather contemporary art space, though everything was shuttered and locked on the gray day that I strolled reverently around the perimeter. In the shadow of the reconstructed city, I tried to imagine what it must have been like for Vonnegut as he emerged from the meat locker. “Dresden was like the moon now,” he wrote, “nothing but minerals. The stones were hot. Everybody else in the neighborhood was dead.” In the days that followed, he would be impressed onto the work crews that cleared the rubble and incinerated the felled bodies.

I also tried to imagine my grandfather. When Vonnegut arrived with his steno bound notepad at the GE plant in Schenectady, my grandfather had just returned from the war. He was a tool grinder at GE; maybe even one of those veterans that Vonnegut liked the best.

Why is it that it’s always when we’re farthest away, we think most about the places we call home? “Well here we are, Mr. Pilgrim,” the clairvoyant aliens, the Tralfamadorians, tell Billy as he struggles to understand the confounding shape of time and chance and memory, “trapped in the amber of this moment. There is no why.”