Sonja Livingston Resurrects Long-Dead Women in Hybrid Essay Collection

Through Sonja Livingston’s literary prowess, women long dead become reanimated in Ladies Night at the Dreamland. In this collection of hybrid, often lyrical essays, we sit beside blood-splattered lovers in 19th century Tennessee, sway on a steamer across Italy with a fatally ill woman, hear ghosts knock at the command of two New York sisters at the dawn of spiritualism, all because of Livingston’s mastery of perspective.

Sometimes the essays are fragmented, sometimes braided. Sometimes they’re peppered with newspaper headlines or excerpts from long-lost letters. They are collages of memoir, poetry, essay, historical fiction, theatre, literary journalism, and murder mystery. They are searches for women who were lost to history and or even to fantasies, such as was the case with “Twyla.”

Twyla once had the phone number Sonja does, in this whiskey-sensual flash memoir. Someone still thinks she does. He calls periodically and asks for her: “Twylathere? The voice, as if hammered from bronze, only warmer, the month of August, all patina and heat, as if the night itself had reached out and dialed my number. Twylathere?” Livingston captures yearning, holds on to it, savors it like nocturnal campers watching the last embers of their fire fade. The dialer’s repeated attempts make her long to know the sought-after Twyla. Perhaps she wishes to be that sought-after too.

That’s one of few essays to have an I-centric narrator. Livington’s talents are many and deep, especially her ability to thwart narcissism. She remains at a remove or places herself Where’s Waldo-deep in the stories’ backgrounds, and never formulaically. As she quipped in a Kenyon Review interview, “I realized that no matter how much I might wish otherwise, I’m probably never going to be very comfortable in the spotlight.”

Livingston writes about the spotlight in “Big,” an essay about jazz/rockabilly/soul singer Mabel Louise/Big Maybelle. This essay exemplifies her clever ability to blur the lines between omniscient and first-person narrator. Here, Livingston refers to herself in the first person as the narrator spilling facts in a literarily journalistic fashion. She also refers to herself that way as the narrative morphs into historical fiction and she becomes an audience member at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. “[I]t’s the crowd I watch—the field of faces lit by booze and music, an army of starched soldiers coming unstuck, something starting up in their chests. How they listen, the Newport crowd, how they watch the revelation on stage while nodding their heads…”

Her dexterous ability with suspense and intrigue seem deeply ingrained as if she grew up among stacks of mysteries. Take her essay on tightrope walker Maria Spelterini, “The Opposite of Fear,” her instance.

“And when she appears finally before them, it’s not only her confidence that heightens their blood but the skirt barely covering her rounded thighs. In her flesh-colored stockings, the young woman’s legs look magnificently undressed as she steps onto the rope strung over the Niagara River Gorge.”

“Dare” is an essay pondering the mysterious disappearance of the late 16th century Roanoke, Virginia colony. This epistolary essay centers on Virginia Dare, the first English child in America, “the first American ghost.” The narrative arc rises like a firework’s tail, filling readers with patriotic curiosity; it crests with a resounding boom to delight with literary awe; and then sparkles out like a fading embers, compelling us to ponder the stark realities of our forefathers. Read it here in Waccamaw.

Livingston’s diversity of unknown historical figures make for such an engrossing read, it’s clear what cerebral fun she had when gathering and synthesizing this book. She makes these figures her friends, her neighbor, her family, inhabits their personae, an actress trying them out for a spin ‘round the stage for a night or two. The end result is that she breathes such life into these places and people that it’s not a surprise they become part of our own memory.

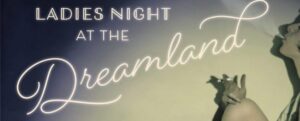

The University of Georgia Press, in its CRUX series of literary nonfiction, published Ladies Night at the Dreamland and Ghostbread, her debut, which won the AWP Book Prize for Nonfiction. UGP’s designers must have understood Livingston’s gift for double entendre: they designed the sepia-toned cover to contain a scantily-clad woman smoking with Mae West’s assertion atop a pedestal. They also designed it with half her head out of frame.