Stories Strangely Told: Stuart Dybek’s “Misterioso”

Stories Strangely Told is a monthly series that explores formal experiment in short-form fiction.

When I was young and delighted easily and time during the summer was a constant sort of low-level mystery, pulling and stretching in a warm taffy way that had little to do with the mechanical workings of a clock, one of my favorite things to do was to read during commercial breaks. Michael Crichton, R. A. Salvatore, Agatha Christie, Tolkien. Stories that crashed into the abrupt starts of TV shows. And those shows’ commercial breaks sweeping back into quick action-heavy prose. It was a beautiful sort of ride; whole days could pass by like this, unencumbered. It was perhaps the media equivalent to eating of a whole lot of M&Ms between Twizzlers.

I was thinking recently about reading as a kid when I picked up a book that’s been on my shelf for a while. The book is Ecstatic Cahoots by Stuart Dybek, published in 2013. It’s a collection of what are sometimes called short shorts, or very short stories, or micro-fictions, or prose poems. My old commercial-break stint came to mind because the first story in the collection, titled “Misterioso,” I certainly would have hated at age twelve. Get ready, it’s a short one; the whole thing goes like this:

Misterioso

“You’re going to leave your watch on?”

“You’re leaving on your cross?”

(That’s it.)

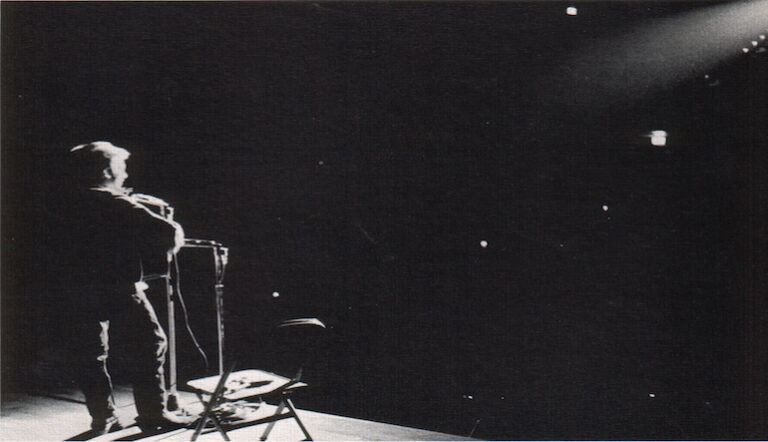

There are elements to “Misterioso” I’d have understood as a kid and elements I wouldn’t have gotten. I wouldn’t have seen the implication of an afterlife, for example, but I’d have gotten the reference to sex. I couldn’t have explained the watch and cross as forms of attachment, but like any kid with an internal world I’d have gotten the general feel. I definitely wouldn’t have noticed the odd in-medias fact that the first line is indented. (The opening paragraph of any prose piece, even if it’s dialogue, traditionally starts at the page’s flat left.) Though I liked jazz I hadn’t made it to hard bop, so I wouldn’t have seen the reference to Thelonious Monk’s 1958 “Misterioso,” a sultry eleven-minute endeavor with sluggish cymbal and not much by way of traditional melody.

What I’d have disliked most about Dybek’s story is its empty unclimactic brevity. It fizzles out too quickly. It doesn’t give easily to the commercial break. And though as a kid I had less training as a reader, by no stretch of the imagination was I a worse one. In many respects as children we are master readers with limitless frontiers, free of those adulthood taxonomies telling us what stories are worth our time. When we’re young we put down books we’re not enjoying, we lean into vivacity and humor, we’re quick to suss out inauthenticity. Complex thought, linguistic prowess, sharp attention spans—these come later. But the tricky thing about contemporary experimental prose is that authenticity is hit-and-miss. Plenty spurts up from the fountains of humility and reverence, but just as much comes from those scummy ponds of anxious intelligence, a desire to break into the market, attempts to wax the ole ego.

Lying on my sofa in the bright Pacific Northwest summer, air pushing in from the open windows and warm static coming off the TV, the stories I liked had big twists and surprise revelations and heaping spoonfuls of suspense because, well, that’s essentially what life was at age twelve. It’s the big question of youth: What happens next? Which, as it turns out, is a fundamentally different question than the question of run-of-the-mill adulthood, which goes something like: Shit, pump the brakes, what the hell is happening?

Which it’s here we get to the tricky part. Because as you know there’s a whole lot of money and influence and power to be made off of us confused sad-sack adults by a nasty tapeworm that’s evolved high-octane parasitic techniques in convincing us that somewhere over there is a solution or answer or reason not to worry our pretty little heads about the Shit question. In other words, as much as I still might enjoy a good romp through Jurassic Park or Salvatore’s Underdark, what I can’t do is lie and say these books give me any new skills in (1) confronting this more pressing question, or (2) figuring out how to build up any sort of anthelmintic reserves to that long-reaching tapeworm that wants to answer it for me. “Misterioso,” by making me a little confused and curious and just a tad more awake to what exactly might be happening in this little word-object right in front of me, does something definitively different than Crichton’s stories—which sure, get me all pumped up and excited, but do so by tapping an old reserve I don’t really use anymore. Dybek’s “Misterioso,” in other words, is delicately and gently trying to tune me back in. Which, as it turns out, is another major deficit to adulthood. Unlike kids we seem to need a consistent near-ridiculous daily regimen of little reminders to step out of our own heads and pay attention to the stuff right in front of us.

There’s another short in Ecstatic Cahoots titled “Fiction” that describes a strange sort of magic amber pendant worn by a lover: “Each night it changes shape—one night an ellipse, on another a tear, or a globe, lunette or gibbous.” It’s the same mutability that makes fresh language and narrative so life-giving. An art that constantly changes contour is an art that keeps us free, keeps us questioning and alive. Or as Dybek writes, to close:

Fiction—“the lie through which we tell the truth,” as Camus famously said—was at once too paradoxical and yet not mysterious enough. A simpler kind of lie was needed, one that didn’t turn back upon itself and violate the very meaning of lying. A lie without dénouement, epiphany, or escape into revelation, a lie that remained elusive.