Stray Reflections: Korean Literature in France

Livre Paris, France’s annual largest book fair, took place last weekend, and the invited country this year was South Korea, in honor of the France-Korea Year, celebrating 130 years of cooperation between the two countries.

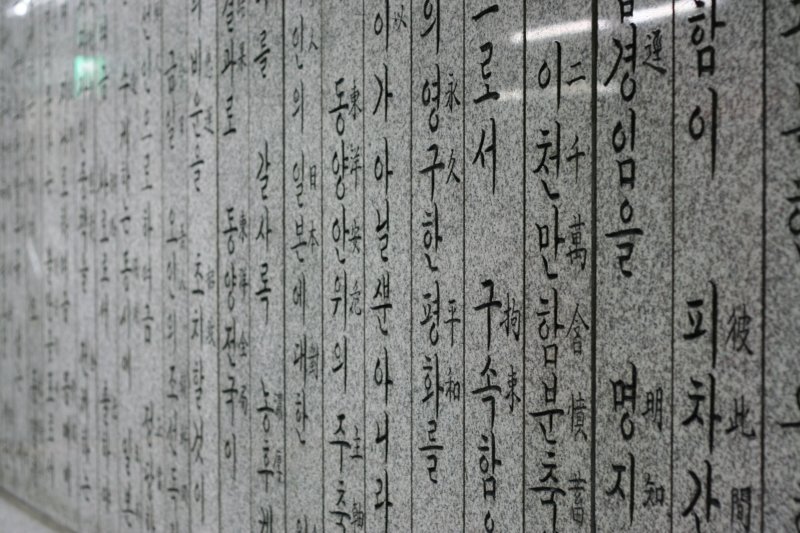

Interest in Korean culture has grown exponentially over the last few years. Lack of strategic marketing and distribution networks, cultural barriers, and differing conceptions of translations have been major hurdles for the overseas recognition of Korean literature, and their effects still linger; but things are starting to shift. The Korean shelf in indie bookstores is now expanding and being recognized as a major literature alongside its Chinese and Japanese neighbors. In France, small presses have been highly active in the circulation of Korean works: Decrescenzo, founded in 2012, devotes its whole catalogue and a literary magazine to contemporary Korean literature; Actes Sud, a well-known and respectable publisher, also has quite a substantial number of titles to its credit. Korean studies have been flourishing, and the number of French students learning the language is ever growing.

It’s hard to say whether this growing receptivity to Korean literature has been bolstered by hallyu (the Korean Wave of pop culture and entertainement), or whether it’s developed independently—something Livre Paris plays on, inviting manhwa and visual artists like Puuung, popular with the younger generation, alongside famous Korean authors, like Lee Seung-U, Kim Hyesoon, or Hwang Sok-yong. It’s also hard to assess the role exoticism and Orientalist curiosity play in this growing interest, even though they do shape to a certain extent the way Korea and Korean literature have been represented in media. In any case, Livre Paris sought to create transnational cultural connections between France and Korea, to move beyond mere economic partnership. Multiple autograph sessions were programmed throughout the weekend, as well as multiple conferences that both highlighted Korean culture and established a transnational dialog. Roundtables on classical Korean literature, contemporary women writers, and the influence of globalization, to name just a few, took place in the Korean Pavilion, managed by representatives of the country’s major cultural organizations. 30 prominent Korean writers and artists were present in total during the festival; Korean children’s books, K-comics, and ebooks were also showcased.

All in all, this portrayal of South Korean literary culture aimed at showcasing the best and brightest in the Korean literary landscape and at appealing to the diverse audience of the fair—consequently, the more profound and necessary reflections on politics and literature did not take place, or if they did, it was offstage. Hardly any mention of North Korean literature overall, though books written by North Koreans were certainly sold on the bookstands: Des amis (Friends), for instance, which is considered as part of the official North Korean contemporary literary canon. It was the first North Korean work to be published in France (and Europe), written by Baek Nam-ryong and translated by Patrick Maurus in 2011. I also heard people talk about Bandi’s La Dénonciation (The Denunciation), which came out in French earlier this month and which has been marketed as a short story collection from a North Korean writer who still lives in North Korea and uses a pseudonym in order to avoid being detected. Not showcasing North Korea does make sense, since it was South Korea that was invited, but this got me wondering about how, with the French literary world opening up to Korean culture, perennial debates have been revived about the role and modes of translation in certain geopolitical contexts.

The Denunciation materializes these interrogations. Critics have been divided on both the text’s literary quality and authenticity: while many literary bloggers have praised it for offering a poignant and incisive glimpse into a horrific reality, experts and scholars of North and South Korean literature (including Maurus) have alternately called the writing style “bland,” “slightly indigestible” (supposedly the hallmark of North Korean prose), and “atrocious.” Beyond the chuckle this litany of adjectives may inspire, the (mild) controversy the book has engendered in French literary circles points to the necessity to rethink the way Western readers receive Korean literature, whether North or South. It’s not so much about whether the translation is good or bad, or whether the original has any literary merit at all; rather it recenters the debate on the politics of literary creation and translation.

Translating books from a literature that is initially not well-known among the target readership implies much more than sticking to the original or capturing its spirit: the representation of an entire culture is at stake. Whether your first foray into Korean literature is a classical text of sijo poetry, or a young South Korean author grappling with contemporary themes, or a North Korean author who writes about life under the totalitarian regime, your reaction and expectations will greatly differ. Market considerations are also at play: if publishers want to ensure the success of a translated book, will they go for one that’s reminiscent of the literary codes and tropes of the target language, or one that’s, radically different, that magnifies cultural difference and may put off prospective readers? In short, how willing are we, as readers, to be taken out of our comfort zone?

The growing interest in Korean literature, as well as the unique stage offered by Livre Paris, could very well spur a broader discussion on the reception of literary works in certain geopolitical contexts and on the construction of national entities. Translation as a tool for transcultural understanding is nothing new; in the case of Korean literature, it’s maybe time to take it one step further and valorize translation not just as a broadening of cultural awareness but as a unique site of political and literary negotiations of voice.