Sudden, Gradual Change

I had been trying to get my 4-year-old daughter to put her face in the water at the pool for two years before she just suddenly did it one day—one night, really, near the end of this summer, the light dying, the rest of us standing poolside with our shoes on and our bags packed telling her come on, get out, time to go home. She’d been able to swim for over a year, but she’d always dog-paddled with her chin tipped so far up toward the sky she couldn’t even see where she was going. We had tried teaching her to blow bubbles, tried goggles, tried getting her amped up about retrieving submerged things from the pool bottom. Water anywhere near her nose and mouth terrified her.

Until this night, when instead of getting out of the pool she looked at us, pushed off the wall, and put her head under.

I had a fiction professor in college who once, in discussing a story ending (probably mine), wrinkled his nose and said, “But do you really think people change?” I know what he meant. There can be a cheesiness, a come-to-Jesus-ness, to moments of sudden awareness or reversal in a narrative. Charles Baxter has written a whole essay, “Against Epiphanies,” on this artistic problem. Loaded realizations can smother the characters who are supposed to be having them. They can make us feel the hand of the author dropping in, pushing down on the person we’ve spent a story with with a crushing weight: the overwrought set piece of The Point.

Yet it is also true that one of my frequent complaints about some fiction is that nothing changes. The change I crave can take many forms, and it doesn’t have to be lasting, and it can even be a significant non-change (a closing-off of the possibility of change can do just fine)—but it has to be there. Without it, the story is not a story but a situation or portrait or description. It does not go anywhere, or at least it does not arrive. And if these moments of arrival—sudden changes, dawning realizations—can be some of the worst moments of not-very-good fiction, I’d argue that in good fiction they can be some of the most sublime.

When they work, the change is often not quite as sudden as it appears—or is only that way in part. It’s a last surge forward of an already moving current. The end of Jhumpa Lahiri’s “When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine” contains this kind of change-moment, and one I love. Over the course of the story, the narrator, Lilia, looks back on a series of visits Mr. Pirzada, her Indian parents’ Pakistani acquaintance made to her family’s house the fall she was ten. He comes in part to watch the news on their television and hear word of events in war-torn Dacca, where he has left his wife and seven daughters, from whom he has not heard in months. The story is largely about the deepening of Lilia’s empathy, the growth of her understanding that the world contains dangers that cause suffering, and that this man in front of her is suffering them. At last, Mr. Pirzada goes back to Dacca to try to find his family—and sends a postcard to Lilia and her parents, reporting that miraculously, his wife and seven daughters are all safe. In response, Lilia experiences an upheaval:

Though I had not seen him for months, it was only then that I felt Mr. Pirzada’s absence. It was only then, raising my water glass in his name, that I knew what it meant to miss someone who was so many miles and hours away, just as he had missed his wife and daughters for so many months. He had no reason to return to us, and my parents predicted, correctly, that we would never see him again. Since January, each night before bed, I had continued to eat, for the sake of Mr. Pirzada’s family, a piece of candy I had saved from Halloween. That night there was no need to. Eventually I threw them away.

The nonsensical but crucial-feeling ritual Lilia has observed in order to try to keep Mr. Pirzada’s family safe is no longer necessary; their crisis over, the Pirzadas no longer seem to belong to her. She has wished them well, but upon learning her wish has been granted, she finds herself curiously bereft. It’s a change that surprises us, and her, and that seems to come all at once—“only then”—in response to the sudden reversal of Lilia’s expectations. Yet it makes such perfect emotional sense, I think, because Lilia’s understanding here is not quite as instantaneous as she thinks. Throughout the story she has been learning about the nature of the connections people have to one another, what strains and forges them. She has done her best to read Mr. Pirzada’s face as he watches their television, “composed but alert, as if someone were giving him directions to an unknown destination”; she has wondered if he dresses so carefully in case he should need “to attend a funeral on a moment’s notice”; when tensions escalate and threaten her parents’ country and relatives too, Lilia has observed the way they and Mr. Pirzada are united by their suffering, “sharing a single meal, a single body, a single silence, and a single fear.” All along we’ve been watching Lilia learn to decipher loss. It’s just that only here does she learn to apply that lesson to herself.

George Saunders’ “Escape from Spiderhead” ends with another glorious epiphanic passage that’s sudden, but not entirely. Our narrator—a convict who’s been forced to participate in mood-and-self-altering medical experiments—finds his perspective expanded at the instant of his death. All at once he’s able to see everything about himself and his fellow subjects:

. . . killers all, all bad, I guess, although, in that instant, I saw it differently. At birth, they’d been charged by God with the responsibility of growing into total fuck-ups . . . In that first holy instant of breath/awareness (tiny hands clutching and unclutching), had it been their fondest hope to render (via gun, knife, or brick) some innocent family bereft? No; and yet their crooked destinies had lain dormant within them, seeds awaiting water and light to bring forth the most violent, life-poisoning flowers, said water/light actually being the requisite combination of neurological tendency and environmental activation that would transform them (transform us!) into earth’s offal, murderers, and foul us with the ultimate, unwashable transgression.

This passage reads as a death-enabled leap into omniscience, a new way of seeing that happens only “in that instant.” Throughout the story, though, our narrator has found himself tripping up against his fellow prisoners’ humanity. Watching one suffer a particularly horrendous fate, he thinks, “Poor child . . . poor girl. Who loved you? Who loves you?”; another breaks his heart with a “happy little shuffle” she does when she thinks herself alone, showing the joy she still feels in living, in spite of everything. In the story’s final passages our narrator reaches a new understanding of the nature of blame—a new ability to reconcile his sense of these people’s worth and inner richness with the reality of their guilt, and to understand that both are equally real. But really the move the story makes here is just a more sweeping version of the moves it’s been making all along.

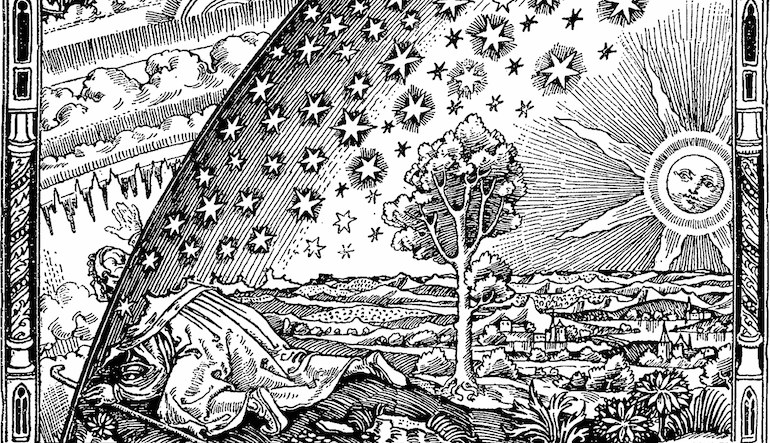

I think of the epiphanies of both of these stories—and of most effective epiphanies in fiction—as being like jumps forward on those moving walkways you sometimes find in airports. The changes in these moments are real, but in some way they are still not departures. They’re part of a pattern set up long before the moments themselves, and their tremendous momentum derives in part from those patterns.

This is true for my daughter too, I’m sure. In all of those moments when it looked from the outside like she was as far from putting her face in the water as she had ever been, she was actually getting ready in ways we couldn’t see. Summoning up her courage, waiting for the one night when it would all add up to enough for her to take a breath, hold it, put her face in, and swim.