Lucy by the Sea’s Pandemic Year

It seems—for Lucy, and perhaps for Elizabeth Strout herself, and perhaps for us all—that community is the thing that will help us get through to the end.

It seems—for Lucy, and perhaps for Elizabeth Strout herself, and perhaps for us all—that community is the thing that will help us get through to the end.

As Angie pities Simon, Mia pities Elena. This is one of the roles, it seems, of the artist pitied by a conventional community: to voice the truth about people, the mistakes they won’t admit to themselves.

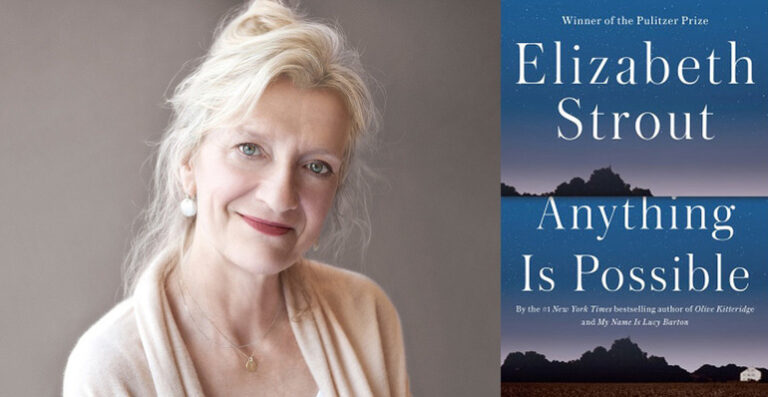

New novels by Maria Kuznetsova and Elizabeth Strout, written in the form of chapter-length stories, give us the opportunity to see a great span of a life and to focus in on the moments that matter.

The adult-man-plus-teenage-girl plot is a common enough version of the coming-of-age narrative, and I’ve recently revisited two novels with it, both written by women: Sue Miller’s Lost in the Forest and Elizabeth Strout’s Amy and Isabelle.

Each day after her husband’s death, Olive Kitteridge runs down the clock until she can go to bed with the sun. She has her routine, but it feels purposeless. Olive made me wonder if the days felt like this to my mother after my father’s death.

Why are rural communities so often the target of linked story collections?

Every once in a while the short story gets its moment in the literary spotlight. It happened in 2008 when Elizabeth Strout’s linked story collection, Olive Kitteridge, won the Pulitzer Prize; and again in 2013 when the Nobel Prize committee recognized Alice Munro’s lifetime achievement in the form.

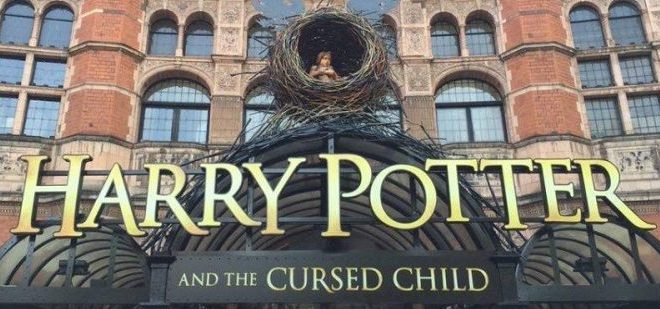

From the highly anticipated “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child,” to the announcement of the Man Booker Prize longlist, here’s some of last week’s hottest literary news.

No products in the cart.