Crossing Boundaries in Whereabouts

Jhumpa Lahiri’s new novel beautifully showcases the way we experience life: the moments that are most important—the turning points—are often only realized in retrospect.

Please note that orders placed between February 1-February 17 will not be shipped until February 17. Thank you for your patience.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s new novel beautifully showcases the way we experience life: the moments that are most important—the turning points—are often only realized in retrospect.

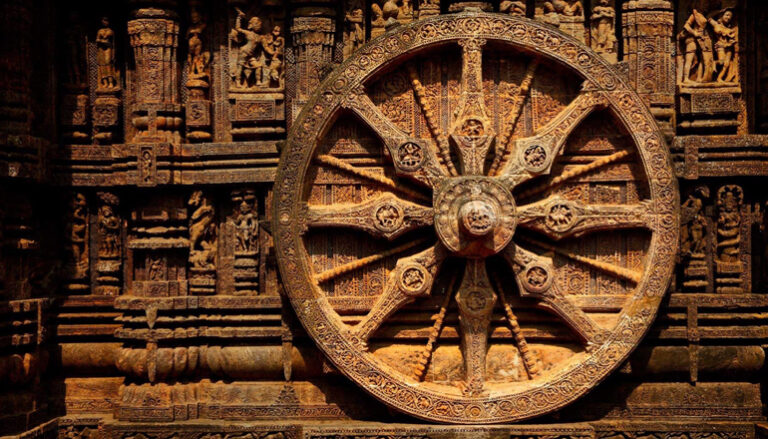

In rendering Homi Bhabha’s concept of the unhomely, or “the estranging sense of the relocation of the home and the world—the unhomeliness—that is the condition of extra-territorial and cross-cultural initiations,” through the sounds and daily events of a young girl’s life, Jhumpa Lahiri exposes a particular formation of unhomeliness inherent to diasporic experience.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s work in Italian is reminiscent of liturgy books with Koine Greek on the left side and English on the other. That she includes the “little brother,” a moniker she’s given Italian, in her 2015 book—and on the left side—is a reversal of the norm.

It doesn’t take much formal study to read a novel in another language, if you don’t mind being unable to understand the occasional sentence or paragraph. It depends more on guessing and sympathy with a particular language or culture than it does on a knowledge of grammar or vocabulary.

I had been trying to get my 4-year-old daughter to put her face in the water at the pool for two years before she just suddenly did it one day—one night, really, near the end of this summer, the light dying, the rest of us standing poolside with our shoes on and our bags packed telling her come on, get out, time to go home.

When I first read Pulitzer Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri’s long short story “Hema and Kaushik,” I lived in suburban Mumbai, where I often sat in darkness by the window at night all by myself. In Koparkhairane, twenty-four miles from downtown Mumbai, power outages were common.

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s stories, immigrants live in a world defined by language, its possibilities, its dead-ends. The legal and political aspects of immigration don’t appear to be the biggest cause of trouble for the characters. Language, however, that first branch of culture, is another matter: characters must continuously code-switch, juggle, negotiate, conceal, and readjust.

During my adolescence, I fell in love with a language before I fell in love with a human being. In high school, in India, a former colony of the British, I came to like – and then love – the English language. The first words I had learned as a baby were Bengali.

His voice a thin radio rasp, Neil Armstrong coaches Buzz Aldrin down the ladder of the Lunar Module. “It’s about a three footer,” he says of that last step to the chalky surface below. The second man on the moon leaps from the final rung and lands buoyantly.

No products in the cart.