Lessons from a Year in Translation

That number is low, but looks good next to the fact that only about 3% of all the books published in the US are translations, a number that grows even smaller if you focus on literary fiction (roughly 0.7%).

That number is low, but looks good next to the fact that only about 3% of all the books published in the US are translations, a number that grows even smaller if you focus on literary fiction (roughly 0.7%).

I’ll admit that I do believe in knowing about the author when I’m reading a book. The limits of an approach that is basically all about the text, and nothing but the text – so that taking into account biographical or historical elements, in short replacing the text within its context, is seen as heresy – are self-evident, even though this approach still exists and has its champions.

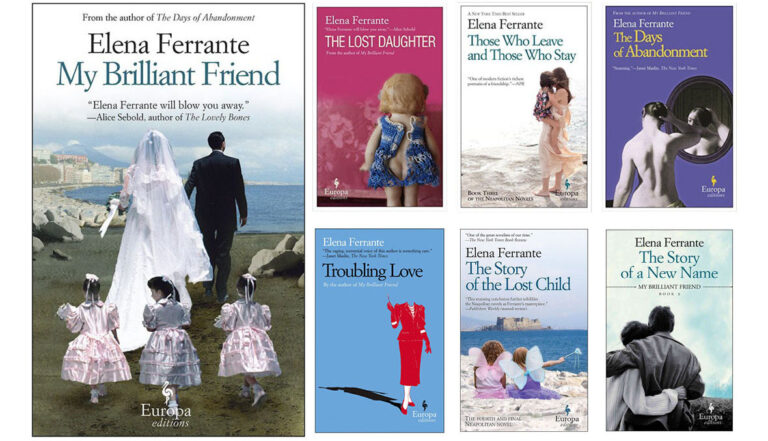

I was on book three of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet when I told a friend that Lila, the book’s second protagonist, is one of the most amazing literary creations I’ve ever read. “But she’s not a creation,” my friend responded. “She’s obviously real.”

It seems as though people do not want to believe that fiction can be intimate—that is: detailed, personal, private, sacred, something with which readers feel closely acquainted or familiar. It is especially surprising if it is also broad, and that one book can accomplish both apparently astounds reviewers.

No products in the cart.