Sketching and Writing: A Visual Artist’s Perspective

The most valuable lesson writers can learn from the artist’s practice of sketching is to remain loose and not treat your work too preciously.

If this lesson wasn’t learned quickly in art school, you were doomed to fail.

In figure drawing, the first thing we had to do was exchange our sharpened pencils for a thick piece of charcoal. We were instructed not to hold the charcoal too tightly, and to keep our bodies loose. A pose would often last as little as five seconds, but we were expected to capture the whole thing.

Through this practice we learned to quickly suggest a pose in a way that allowed the viewer to understand the whole thing. Sketching trains the artist to rendering the essential features of a subject and discard redundant detail. And is this not what fiction writers strive to do?

In figure drawing the pose changed so quickly that all our sketches would end up on the floor. We might save or look at one or two, but more often at the end of session we’d scoop them up and throw them out. The purpose was never to keep the drawings but to learn from them.

One of the most regrettable things a visual artist can do is let these drawing skills get rusty. When that happens, we bemoan the fact because it means we’ve fallen off a regime that has kept us sharp. For this reason, I keep a sketch book in every drawer.

My habits as a writer are an out growth of my training as visual artist and I’ve transferred this practice of sketching into my writing.

I use all available devices; on post it notes and index cards, in voice memos on my phone and emails to myself, I make quick notations. Ideas and thoughts, like changing poses, often occur very quickly. The most efficient way to capture them is to jot them down loosely. When I do this I don’t bother with perfecting language or completing sentences. None of this matters since these annotations are only for myself. One of them reads, “the way she walks, regal, bird-like, peacock.”

Contained within these notes, there may be a thread worth pursuing. Frequently there is not. But there is value simply in the act of exploring them.

Inklings and hunches, diagrams and impressions, concepts and descriptions—once I scribble them down, I don’t always look back on them.

Writing down my thoughts brings them into consciousness, and this is often good enough. These broad, loose ideas are sometimes more useful when working in the background of my subconscious.

At the foundation of most masterpieces, there were lots of sketches. Rough unfinished drawings that explore form, quick thumbnail sketches or studies that plot out composition, are made only to be thrown out or painted over. Through X-rays we can now see how painters build their canvases layer by layer, each stage revealing another loose drawing.

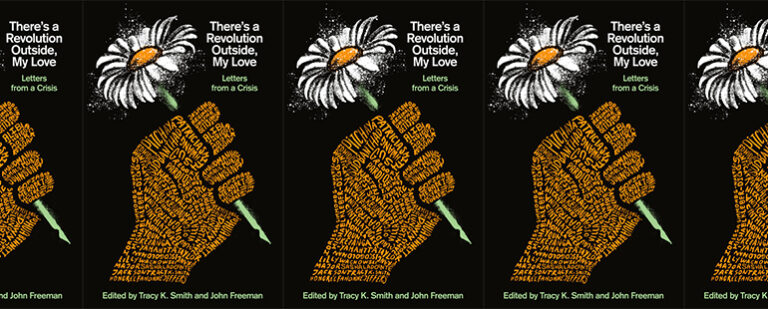

Drawing by Annie Weatherwax