The Best Short Story I Read in a Lit Mag This Week: “How Héctor Vanquished the Greeks” by George Choundas

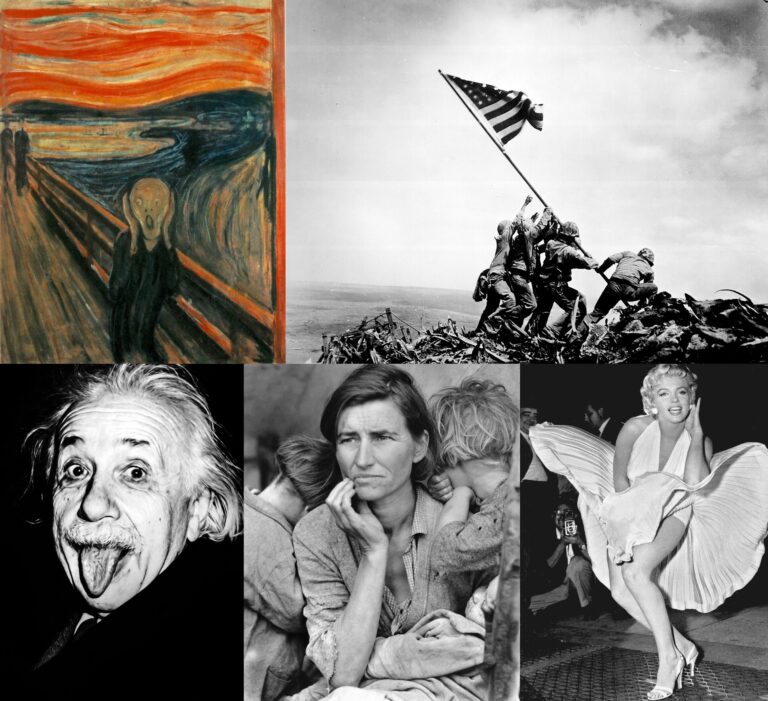

The relationship between sports and war in American culture is deep; tune in any given Sunday and you’ll find fighter jets flying over the stadium and football jerseys designed with camo. In “How Héctor Vanquished the Greeks” (Harvard Review), George Choundas explores the kinship between war and sport through a youth soccer game woven into Greek mythology.

The Hector of myths was famous for being the greatest of the Trojan Warriors, killing over 30,000 Greeks in his defense of Troy. The narrator Héctor is an eight-year-old kid from Puerto Caballo, Venezuela, who Choundas reveals is constantly trying to outdo his older brother Severino’s soccer exploits and win the attention of his busy parents.

“He envies his older brother in a way his parents have persuaded themselves is healthy and natural. He spends hours each day perfecting a different fútbol technique, a prodigious number of hours his parents have decided to decide is also healthy and natural because they have too many other things to worry about.”

In this case, “healthy and natural” competition and desire for attention births in Héctor a soccer technique is as strange as it is effective, one that also reflects back on another famous mythological story, that of the Trojan Horse. Héctor tucks the ball between both legs and rolls “like a beetle down the field with the ball safely ensconced—not once touching the ball with his hands—and scores a goal.” No one can stop him, and for the time being, he’s won the arms race his older brother, if not the attention of his parents.

The biggest test for Héctor and his technique comes on the weekend, when the boys’ father drives them to port, where each Saturday they play pickup games with merchant mariners from all over the world—some posing greater challenges than others. The Greeks, we find, are their “grimmest adversaries,” and today they’ve arrived in “a vessel from Cardiff by way of Tampa carrying multifoil insulation and pneumatic drills.” With the game is tied at nil-nil, Choundas describes Hector in action.

“Héctor gains possession. He deploys. He drops to the ground, wraps himself around the ball—more tightly than ever—and flows down the field, around the legs of two stunned Greek defenders, straight into the goal. The Greek goalkeeper stands to a side, pointing a bladed hand at Héctor and gazing upfield and asking with his whole body, “τι είναι αυτό?”—“What is this?”—half-flummoxed and half-indignant.”

With the verb “deploys,” Choundas subtly reminds us that though this is a mere soccer game, it mirrors that of a military engagement. As the story continues, Choundas reveals through the teams how closely innovation is tied with escalation. Unable to stop Héctor, the Greeks rationalize violence.

“The Greeks simply start kicking Héctor as if he himself were the ball. Not in a frankly injurious way. But in a rigorous, unyielding, manhandling way. The first time he feels an unfriendly foot, Héctor, alarmed, immediately unwinds himself and springs up and loses the ball to the Greeks and their momentum-shifting goal. Severino, furious for his brother, punches one of the seamen—aiming for the chin but missing and landing a sloppy blow on the shoulder—and storms off the field. But Héctor finds his perseverance, stays tucked against all assaults, tolerates especially the counterkicks of his teammates who are doing their best on defense, and rumbles on. Héctor becomes the ball. Héctor is the ball.”

The actions of both boys are telling. While Severino responds by leaving the field, no longer wanting to be a part of the game, Héctor doubles down, committing even more fiercely to his technique, and in doing so loses the identity that Severino saves by leaving. He is now nothing more than the ball.

Choundas closes the story with a balanced action that reads as both heartwarming and scary. While rolling, Héctor begins biting the other team, and his brother Severino doubles back and begins cheering. Héctor is now a hero, admired by even his brother. That desire within him is for now resolved. But with each cheer, the crowd gives full approval of what has—to use his parents word, “naturally”— become far more than a game, with far darker consequences, one’s that have a precedence all the way back to mythical times.