The Dustbowl

The Dustbowl

The Dustbowl

Jim Goar

Shearsman Books, April 2014

86 pages

$16.00

Buy: book

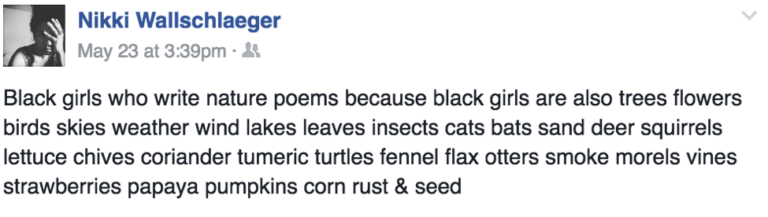

The greater part of Jim Goar’s The Dustbowl is a poem or sequence also called “The Dustbowl,” which the jacket copy describes as “a collection of serial poems.” These poems are, on average, about ten lines long, made up of short, staccato sentences or phrases, often enjambed, and some deliberate compositional process has clearly taken place—a chart at the beginning of the book shows how the fifty-five poems of “The Dustbowl” were taken from a run of more than ninety. But we do not know what the principles of inclusion or exclusion were, or in what way the poems are serial.

One would like to know more, for “The Dustbowl” makes compelling reading. If one were to fall asleep some afternoon having just learned that John Steinbeck published The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights (an adaptation of Malory) as well as The Grapes of Wrath, and then dream a braided dream of Okies pursuing the Holy Grail, and were Godard then to edit that dream, one would have something a little like this book’s title poem.

Unsurprisingly, Woody Guthrie insinuates himself into “The Dustbowl,” as lines from “I Ain’t Got No Home” and “Do Re Mi” (Guthrie’s sardonic caution to anyone who thought “California is the Garden of Eden”) continually recur. Somewhat surprisingly, but just as appropriately, Tennyson is also fleetingly glimpsed—Goar’s “A heart-land turned to dust” recalls Tennyson’s “my heart is a handful of dust,” from “Maud.” Tennyson, after all, had his own go at King Arthur; furthermore, the quest for the Grail played a large role in another poet who evoked “a handful of dust,” and sure enough, Goar’s speaker notes that he

Kept

the Wasteland in my pocket. Turned it over

and over. Dust as far as the eye could see.

The allusions in “The Dustbowl” keep the reader alert, but they do not dominate the tone of the poem, which seems to have more to do with the enormous spaces of the American West: the way those spaces translate themselves into a speech of clipped, elliptical taciturnity, the way they frame quests like that of Browning’s Childe Roland, carried on even though the quester gave up hope of success long ago.

The Dustbowl also contains a section titled “other poems,” written before the undertaking of the title sequence: short, imagistic, each bearing its date of composition, they seem to trace a kind of stripping-away that prepared for the windswept flatness of “The Dustbowl.” As with the work of Jack Spicer, of which Goar is apparently a student, one senses that an intriguing poetics lies underneath the intriguing surface of the poem thereby generated. Someday, we may know more; in the meantime, the poem is intriguing enough.