The Give and Take of Literary Magazines

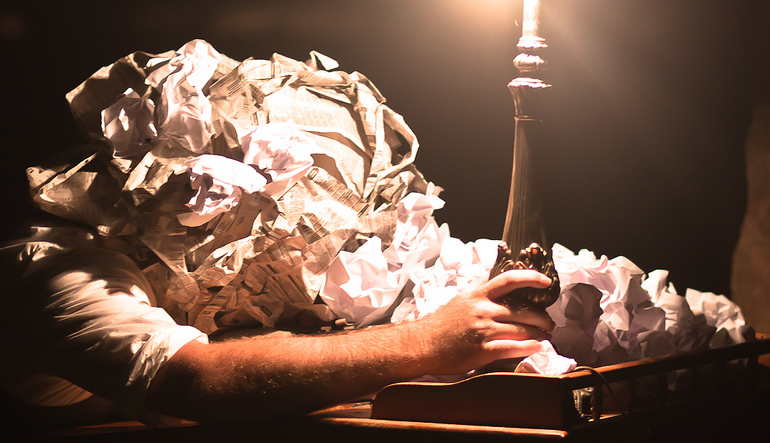

Not long before my friend finished his MFA in poetry and moved away last summer, he mentioned wanting to start a literary magazine, or maybe a press, or both. After editing his program’s student-run journal and reading submissions for various publications, it felt like the right move. But, unsure of where he’d land in the next year, he was worried about finding time for such an endeavor. I offered to set up a monthly Google calendar event reminding him to work on his maybe-project. (Another friend of ours, a disciplined fiction writer, had just started scheduling “poem time” for me, and I felt like I should pay it forward.) For seven months, “think about yr new lit mag” popped up on both of our phones and appeared in our inboxes.

In February, when we caught up, our conversation eventually turned toward talking shop; where we were submitting, the states of our ever-morphing manuscripts, and opportunities one of us thought might be perfect for the other. He was, he explained, still determined to start some kind of publication.

The value—and power—of new independent publishing goes without saying. Fledgling journals undoubtedly provide a much-needed home for underrepresented voices, experimental work, and young writers. And the industry recognizes the contributions these journals make: The 2015 edition of Best American Poetry featured poems originally published in magazines like Powder Keg, which was only a year old, alongside mainstays like The Paris Review; of the twenty stories included in Best American Short Stories 2017, eight were published by independent magazines.

Online publications have proven especially meaningful as the literary community evolves within online spaces. Magazines with free, shareable content like BOAAT, Queen Mob’s Teahouse, and Cosmonauts Avenue enable writers and readers to circulate new voices in a way they can’t with a print publication. As a result, I’ve heard countless poets say they’d rather have their work published online nowadays. “That’s where the readers are,” reports Stephanie Burt in the New Yorker. “Ander Monson’s quirky journal DIAGRAM (poetry, essays, and actual diagrams) reported forty thousand unique visitors per month in 2014.”

But new publishers, operating with virtually unlimited space to publish, also run the risk of taking more than they provide.

Literary journals often lay hold of the tangible—submission fees and unpublished work—in exchange for the notional. Exposure, literary standing. Money, in other words, seems to move in only one direction. If any moves at all.

In “Paying to Play: On Submissions Fees in Poetry Publishing,” Rachel Mennies grapples with similar concerns about the industry’s economics, specifically the absence of money in poetry publishing. Drawing on data collected in her 2016 survey of poets, presses, and literary magazines, she considers whether or not the submission-fee model is “equitable or sustainable for poets and for presses/journals.” Refreshingly, Mennies pushes beyond the played out question of whether it is ethical to charge a writer three dollars in submission fees, instead focusing on whether submission fees, which by publishers’ own admission fund things as variable as software and writer payments, create an impartial, accessible system. According to the data, she explains, submission fees exclude “poorer or working-class” poets while favoring those “for whom it’s more of an inconvenience than an impossibility to lose money or break even.” In other words, poets spend a lot of money over time to have their work considered for publication, but they are not guaranteed to regain it.

Mennies also emphasizes, however, that many of the journals she polled depend on a combination of “editors’ wallets” and submission fees to stay afloat. This suggests a much larger problem with the system we’ve developed and normalized; many editors and publishers work for little to no money themselves. “Lit mag editors are typically volunteering their labor, and even with fees nobody is getting paid,” writes former Electric Literature editor Lincoln Michel, “So it’s hard to feel like you are exploiting anyone when you don’t get any money from the exploitation.”

Most writers and publishers set out to make art, to sustain the literary community and to extend its boundaries, to tell stories and to help readers access those stories. But does volunteer editing and publishing also, in Michel’s words, “devalue” writing?

According to Aaron Giovannone, this “Art-for-Art’s-Sake” mindset can actually be traced back to the Industrial Revolution and eighteenth-century Romanticism. “Powerless in the face of these socioeconomic changes,” he writes, “prominent Romantic writers positioned themselves and their art outside of society.” They separated writing from any need for its “economic justification.” This “defensive reaction” continued into contemporary literary culture, creating a “prestige system” in which we laud work “that seems the least interested in immediate profit” over bestsellers:

Prestige, or cultural capital, turns into economic capital when writers get grants, awards, or well-paid positions on the strength of their literary accomplishments, which the authors pursued while apparently economically disinterested. In poetry’s upside-down economy, in other words, the path to long-term financial security begins with behaving as if money doesn’t matter.

But who gets to behave that way? We end up back at the beginning, with those of us who can afford to exchange the tangible for the notional rising to the top.

In this landscape, rife with controversial financial practices and an ever-threatened National Endowment for the Arts, what would economically responsible publishing look like? If Mennies, Michel, and Giovannone are correct, and the primary problem with our current network of submission fees, volunteer-run journals, and unpaid writers is the absence of funding, then we must first admit that money does matter.

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable, so did the divine right of kings,” explained the late Ursula K. Le Guin in her 2014 National Book Award acceptance speech. “Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art—the art of words.”