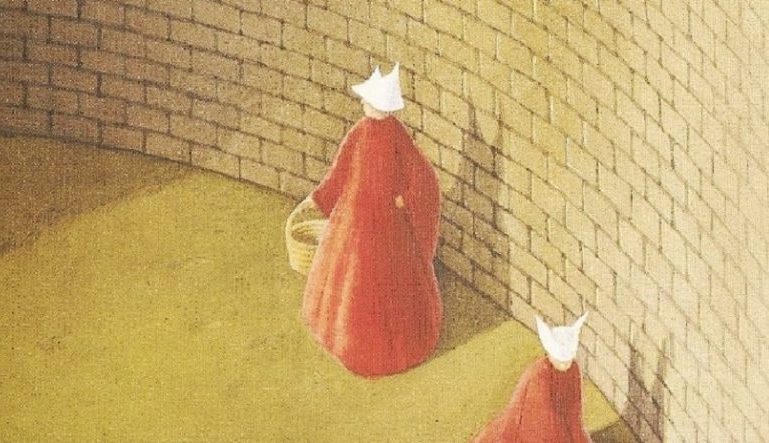

The Handmaid’s Tale and the Silencing of a Woman’s Voice

It’s nearly impossible to deny the social and political relevance of The Handmaid’s Tale. In Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel, critics and viewers alike immediately recognize that the dystopian world of Gilead—where women are stripped of all human rights—is no longer rooted in fiction. And while many have praised the book’s feminist themes, none have noticed that the Hulu adaptation highlights Atwood’s special warning intended for women writers, historians, artists, and documentarians. In a patriarchal society turned radical and violent, a woman’s voice will be stifled by taking away the written word.

The women in The Handmaid’s Tale are oppressed in every possible way, most notably through rape and the ceremonial confiscation of their reproductive rights. They are also banned from reading and writing—a restriction that is not only dehumanizing, but that also deprives women of any chance to record their own history. This loss of literary awareness and power is threaded throughout the book and corresponding TV show—the latter which sees its second season premiering today.

You might not recall that the narrator and main character, Offred (Elisabeth Moss), a handmaid forcefully separated from her husband and daughter in order to become a reproductive surrogate for one of Gilead’s most influential couples, was once an assistant book editor. Offred helped publish novels and academic titles, including “nine volumes on the history on falconry”—which fellow handmaid Ofglen (Alexis Bledel) instinctively scoffs at before remarking, “Actually, that sounds like it’d be fun to me right now.”

It’s no coincidence that Offred was once a woman professionally paid to read, write, and edit who now has no genuine access to words of any kind. In the second episode, when Offred is asked into the Commander’s private study, she stares at his ceiling-to-floor bookshelves in awe; later, while playing an illicit game of Scrabble, she examines the letter-pieces as if she might cry. In episode four, when she’s punished and isolated in her bedroom for weeks, her only solace is a Latin phrase she finds scratched into the baseboard of her closet.

There’s another example of the warning The Handmaid’s Tale provides for women writers. Serena Joy, the Commander’s wife, was a conservative activist and, we’re surprised to learn in episode six, a published author. Her book, A Woman’s Place, while infused with right-wing politics, was also considered a text on “domestic feminism”—something the female leader of Mexico, Ambassador Castillo, quickly points out.

Ambassador Castillo, whose country has not yet embraced the Gilead movement, challenges Serena Joy’s compliance with this new world, asking her directly, “Back then, did you ever imagine a society like this?” Ambassador Castillo interrupts Serena Joy’s formulaic answer by clarifying: “A society in which women can no longer read your book…or anything else.” Here, we finally see Serena Joy’s cool facade begin to crumble. “No, I didn’t,” she admits. In the same episode, in pre-Gilead flashbacks, we learn Serena Joy was previously a prolific writer—writing freelance articles and working on a second book. It’s ironic, of course, that Serena had a hand in establishing a government that now denies her the freedom to do something she had dedicated her life to pursuing.

In our twenty-first century society, literacy and writing remains a form of empowerment and joy, and a path to financial independence for women, though we operate within an industry that’s still dominated by men; in Gilead, the written word in the hands of a women is explicitly a form of rebellion. Nowhere is this portrayed more powerfully than in episode ten, the first season’s finale, when Offred finally opens the package from Mayday—the brown paper package she’s literally risking her life to deliver—only to discover a bundle of letters.

The letters are written on napkins, scraps of paper, even the tattered edges of cardboard, whatever could be spared; the writers are all women, Offred’s fellow handmaids. In the letters, the women record their names (now forbidden) and share their stories, noting when they were captured and where they’re held geographically, sometimes mentioning their previous lives or occupations, the names of their children who were taken away, and the ritualistic rape they’ve endured. The content of each letter varies, but the plea remains the same: help us, remember us, share our story. One such letter reads: “Whoever is getting this, please don’t forget me…please don’t forget us all.” Offred reads each note frantically, fanning her hand over the letters and crying, overcome by the immensity and magnitude. Despite the intensity of the scene, however, this isn’t a somber moment in the life of our protagonist. Offred is smiling through her tears, suddenly flooded with a sense of solidarity and purpose. Thanks to the written word, she no longer feels alone. For the first time in a long time, she has hope for the future.

It’s one of the most powerful and climatic scenes of the show so far, for reasons both obvious and implicit. Throughout the series, we see the consequences of withholding written language illustrated repeatedly by the women who are most affected by its absence. Their stories demonstrate how this loss results in a forced deprivation in knowledge, which restricts a woman’s autonomy in a profoundly patriarchal world. To put it simply: if women are denied the right to record and share their own history, they’re limited in their ability to learn from the experiences of their predecessors. How can they connect with each other, learn from each other, and gain access to the same knowledge men have? Without the ability to access, internalize, and shape written history, women can no longer develop and grow.

When considering the fact that Gilead is intended to be a mirror image of our own society, the loss of literacy imposed upon women in this dystopian universe becomes the regime’s most vicious weapon. In our environment, the ability to read and write is essential if one wishes to climb the socioeconomic ladder. Denying only certain groups of people the pursuit of literacy is an explicit and psychological hate crime, and one America instituted during the colonial and Antebellum eras (and in many ways continues to practice). Through this parallel, we can begin to comprehend the implications associated with refusing women literacy; after all, our own history reveals how the restriction of knowledge quickly escalates into a total abuse of power, and eventually, slavery.

It’s a bleak message, but one The Handmaid’s Tale portrays clearly. In our society, particularly in this political climate, a woman’s knowledge and authority over written language is a social justice weapon that we must protect at all costs. Without access to the written word, women’s value in society becomes consumed by the utility of their bodies. Without the ability to record our thoughts, our thoughts are instantly dismissed, silenced, or forgotten.

This piece was originally published on April 25, 2018.