The Incantatory Effect of Repetition in Memoir

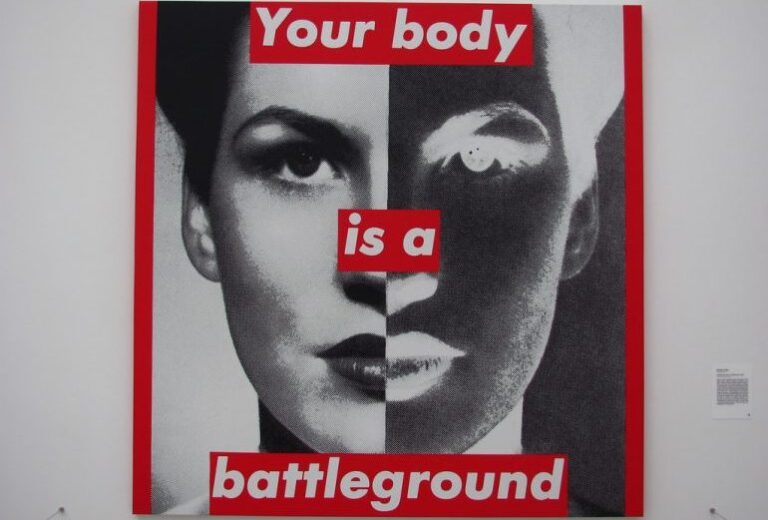

Two memoirs of the past year left me spellbound. They have much in common—Roxane Gay’s Hunger and Melissa Febos’s Abandon Me both deal with longing to be understood and fighting the instinct to try to disappear. They both explore themes of love, desire, and identity, and, to varying degrees, trauma and its aftermath. They are both achingly honest and vulnerable.

But the spellbinding nature of these books has everything to do with language; both use repetition as a literary device to achieve a lyricism, rhythm, and resonance that build power.

In Abandon Me, Febos returns to the same themes over and over, but each time expands to new territory and gives them more context. Early on she describes the fear and abandonment she felt when her father, “the Captain,” went to sea: “The ocean disappears things. It is a hungry, grabbing thing,” she writes. “I was a girl gulping a woman’s grief.”

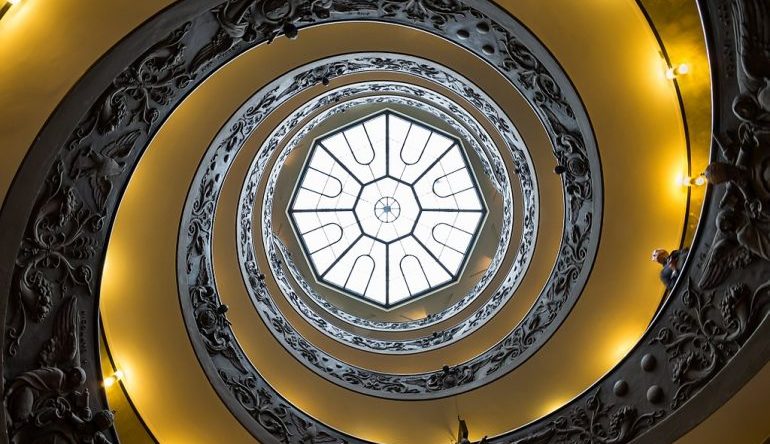

In the seven shorter essays of the book, Febos returns to these girlhood wounds and draws connections to lingering questions about her heritage and an intense and mystifying relationship with a married woman. In seven different ways we learn about the pain and fear of disappearing, and the oceans of a hungry, grabbing desire. In the final essay—the eighth and the longest in the book—Febos tells the story in its entirety, and her voice has the power of a mountaineer who has ascended seven consecutive peaks and is just hitting her stride as she runs circles around them.

Roxane Gay also uses repetition to great effect in Hunger; in this memoir it occurs at more of a micro level, in words and phrases repeated at intervals. I think this is especially effective in writing about trauma—it enables both the author and readers to wade into an emotionally difficult topic in small, steady steps—and it exemplifies the journey of surviving trauma, in the ways one is often forced to revisit the experience and can struggle to make meaning from it.

Repetition sets the tone from the opening chapters of Hunger, with the phrase, “this is a book”:

This is a book about my body, my hunger, and ultimately, this is a book about disappearing and being lost and wanting so very much, wanting to be seen and understood. This is a book about learning, however slowly, to allow myself to be seen and understood.

The language of repetition in prose, like in poetry and song, has a way of seeping into one’s consciousness. Like a mantra, it can have formidable power that might not be evident upon first hearing it. In Hunger, Gay describes her feelings of pain and brokenness after a group of boys raped her when she was twelve. There is agency in the small phrase, “I ate,” and power in its incantations; each repetition builds in intensity, turning and twisting to new meanings, gaining momentum:

I began eating to change my body. I was willful in this. Some boys had destroyed me, and I barely survived it. I knew I wouldn’t be able to endure another such violation, and so I ate because I thought that if my body became repulsive, I could keep men away.

And in later passages:

— “I ate and ate and ate in the hopes that if I made myself big, my body would be safe.”

— “I was broken, and to numb the pain of that brokenness, I ate and ate and ate…”

— “I ate and ate and ate and I became more and more lost.”

Gay says that writing this memoir was “the most difficult thing I’ve ever done,” and it is easy to understand why, given the trauma she discloses and the vulnerability she exposes. She also describes writing Hunger as a confession, and I see that too. But in the rhythmic and lyrical language of her telling, I also hear something of a requiem, a fighting song, a serenade to her girlhood self, and an anthem. In the end, her words sing with strength, claiming the space in which she stands: “Here I am… Here I am… Here I am…”

I see how in both Hunger and Abandon Me, it is not merely the repetition of words or stories that is compelling, but it is also the transformation that takes place in the spaces in between. In each retelling, in each replaying of a memory fragment, in each revisiting of the words and phrases in the story, the narrators change. They dig deeper, become more whole, achieve more power over their life experiences, and as the readers follow along through the repetitions, we are witness to their transformations—and if we are lucky, to ours.