The Interrogation of Trauma, Love, and Work in Made in China

Anna Qu’s debut, Made in China: A Memoir of Love and Labor, out earlier this month, is a memoir centered on—as the subtitle describes—questions of love and labor. Throughout the book, Qu guides readers through her childhood experiences, unpacking her complex emotions around family and trauma, drawing on her time working in the textile factory owned by her mother and stepfather, and linking these childhood moments to her time as a young adult working for a start-up company. Initially, the journey through these memories seems circuitous and almost arbitrary, the links appearing superficial—these things all happen to have been experienced by Qu—but Made in China is more than just a singular person’s experience crystalized into a tidy memoir. The book unravels larger assumptions about immigration, labor, and trauma at both the personal and collective level, demonstrating how many seemingly disparate elements of our lives are deeply connected.

The book’s title, Made in China, plays off Qu’s own identity as someone born in China and who lived there until she was seven. But it also takes on the assumptions that stem from the phrase itself. One reading of the phrase recalls the garment industry in the United States—Qu highlights the link between her family’s story and the history of garment making in the U.S., marking the path that brought her mother from China to New York City to work in a garment factory, which eventually allowed her to bring Qu to the United States, as well. Qu writes:

After 1965, three businesses emerged among the Chinese population in New York as a direct effect of the immigration policy that abolished the National Origins Formula, a largely discriminatory system that restricted immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe. The policy gave opportunities to new immigrants arriving to work, and then start their own restaurant, laundry or garment business.

The story of her family is inextricably linked to the history of labor and systems of immigration in the United States. Qu’s exploration of her family’s garment factory thus gradually unfolds into a complex exploration of inequality and trauma.

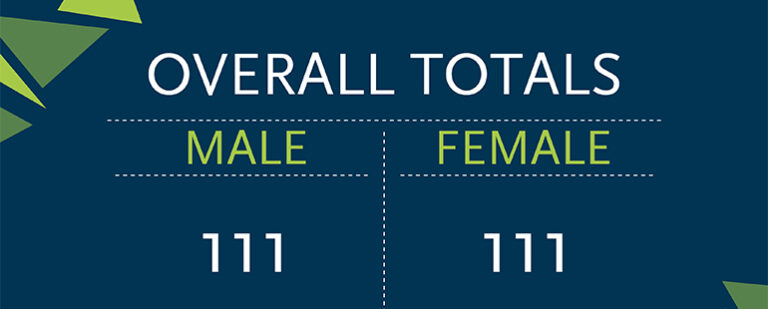

The story of parents who come to the U.S. for work and send for their children once they are able to establish a foothold in the economy is a common one for immigrant families from many types of backgrounds. But Made in China tracks another element of that particular narrative: the ways that human beings inflict harm on one another, regardless of shared experiences or cultural backgrounds, once they reach a certain level of economic stability for themselves. Qu herself describes the working conditions of the family factory as that of a sweatshop, with many of the workers beginning in the same low-paying position that Qu’s mother occupied at one point in time. The economic and financial realities of immigration in the United States are tenuous for so many and Qu does not mince words when it comes to describing her own time working in the factory, snipping threads off completed garments with a group of women. It is a clear-eyed look at a reality that many in the United States would otherwise look away from. Qu manages to offer both context and a critique of these structures.

Qu’s time as a child working in the factory links to another thread that is just as complicated as it is thoughtfully and cuttingly worked through: familial trauma. Though Qu is quick to acknowledge the sacrifices and the hardships her mother experienced to ensure Qu’s livelihood in the United States, her mother’s own unaddressed traumas and internal struggles manifest through her treatment of Qu. She recounts a series of abuses and mistreatment at the hands of her mother that truly makes the heart ache. And yet, like her deft handling of the complexities of labor and the limited opportunities available for many immigrants, she handles her own experience of trauma in a way that is both direct and understanding. At one point, she muses, “I am beginning to realize that we are all raised by children. Children that are shaped by their own traumas, some of them unable to forget or overcome what happened to them before they passed it along.” At the same time, she does not back away from the emotional and mental effects of what happened to her. She recounts her traumatic experiences because they are a part of her story, the story she has every right to tell.

Through this exploration of trauma, Qu highlights a key consideration when discussing traumatic experiences: what constitutes abuse, and who gets to decide what is considered abuse? She writes, “When all is quiet, I am still left facing painful questions. Was I abused at all? By whose definition and what authority do we define abuse? Does it matter? I don’t know if I’ll ever find the answers to these questions.” As readers, it is tempting to demand clear-cut answers to these questions—or to overwrite the author’s intentions and to force our own definitions onto the text. Yes, I found myself thinking to myself as I read through the book, Yes, this absolutely is abuse! But then I took a step back and considered why Qu would take this approach, this willingness to stand in the space of uncertainty and look at it from all possible angles. Made in China reveals the messiness of writing about lived experience, including traumatic experiences, and how tempting it can be to try to force our stories into a clear, set narrative structure or to make the characters in our stories fit archetypes that do not make sense in real life. How could there be easy answers to questions that span history, socioeconomic positions, and family lineages?

Qu’s ability to linger in these gray areas, to face questions that ultimately have no objective answers, to push against the idea that her story needs to have a clear, narrative arc is the most remarkable thing about Made in China. She is able to interrogate without relying on definitive answers, she is able to explore without marking something permanently on the map. And rather than leaving readers with a story that is unmoored or incomplete, she is able to open up new pathways for readers to consider their own assumptions about the topics she touches on: trauma, love, and work. Rather than providing a prescriptive schema for these large themes, she offers an invitation to see how our individual stories are connected to societal structures and to find meaning in unanswerable questions.