The Language From the Far Places: Experiences of Mental Illness in Literature

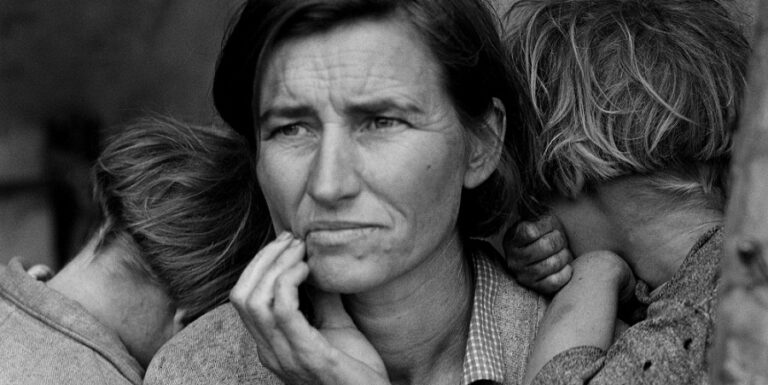

When I experienced a psychological breakdown in my final year of high school, I found one bright, snowy day that I couldn’t speak ordinary words. I just kept repeating the lines of Bertolt Brecht’s poem, “Der Pflaumenbaum” (“The Plum Tree”), over and over. “In the garden stands a plum tree. / It’s so small one can hardly believe it’s one. / It has a little fence around it, / so that no-one tramples it. (…) // This plum tree, no one believes it’s one, / because it never has any plums. / But it is a plum tree. / You can tell by the leaf.”

Trying to say anything else, my brain froze, my jaw locked into the same words, the same sounds, and a kind of scream building up in my chest. I was with two close friends, and as they asked me what was wrong, nothing would come out but the words of the little poem. I beat at my head with my hands, I gulped air, my face felt pinned to the bones of my skull by a hundred thick needles. My friends managed to bring me inside, sit me down on a couch, listening to me, trying to calm me down. Eventually, exhausted, I curled up asleep. When I woke up, my friend was in the next room, but she’d left a little note beside me: you are a plum tree. I can tell.

I was trying to say I was a human, something terrified inside me was trying to say it, please recognize me as a human being. There is something under the skin, the frozen face and beating hands that is human, and needs you to see it.

Sometimes, when language is undone at the root, when the connection between the essential self and the outer layers—of the mind, speech, gesture—is severed, the only way through is through metaphor. We cheat the guards, we trick the sentry. Something, however small, makes it through.

So how can one adequately capture experiences that very often undo language itself, that are often so profoundly isolating precisely because they defy our common speech, our tested vocabularies, and definitions of human experience? How do we find the right words to map that place, to bring some kind of connection with the agreed-upon world of people who can only watch from outside as others go through sometimes horrifying journeys and tortures of consciousness?

I want to stay clear of any romanticization of mental illness as a conduit for heightened creativity. Instead, I look at Joanne Greenberg’s astonishing book, I Never Promised You A Rose Garden (New American Library, 1964), written specifically, according to her, to undo those romantic notions. The book explores in sensitive detail the relationship between the protagonist, Debra, and her psychotherapist, based on Greenberg’s own psychoanalyst, the pioneering and remarkable Frieda Fromm-Reichmann. One of the most striking features of their relationship is the analyst’s recognition of her patient as an intelligent, quick-witted, sensitive young woman. A person, essentially and foremost. “Take me along with you,” she tells Debra. She is one human being speaking to another, albeit at first through the florid, deeply narrative world into which Debra has retreated.

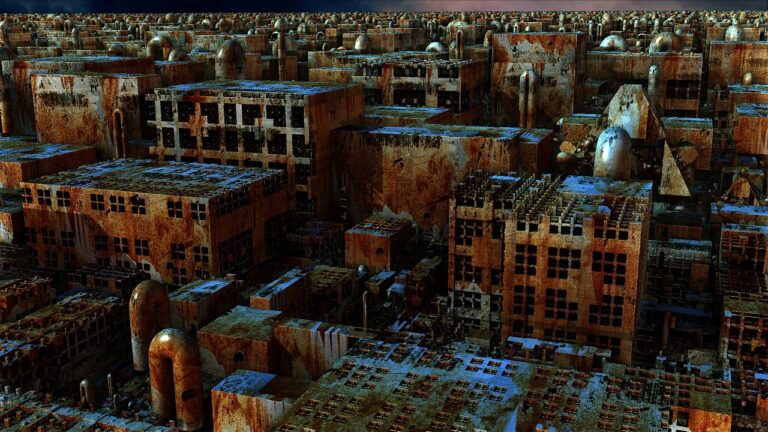

This world is mythic in its proportions, symbolic and suffused with deeply and extravagantly wrought meaning. It is a story, and it is through entering this story that Dr. Fried, the fictional counterpart to Fromm-Reichmann, is able to help Debra, and Greenberg, heal. This is the fundamental idea behind much of Fromm-Reichmann’s work and approach to psychoanalysis, as she insisted that mental illness, and most specifically schizophrenia, was essentially a state of abject loneliness, that could be healed through human connection. If art is essentially a conduit for empathy, the means of finding oneself in another, and thereby connecting with someone even far removed from our own context, then the crafting of story, of art, can be a conduit for the healing. What it takes, however, is a recognition of the human being speaking, however strangely.

In Sylvia Plath’s “The Rabbit Catcher,” one of the most famous and studied poems about experiences of mental distress, Plath’s observations, even in extremis, are devastatingly specific, observed with all the same fierce attention she applies to the world of the everyday, of food, and landscape, and fashion, and people, and historic upheaval. “I tasted the malignity of the gorse, / its black spikes, / the extreme unction of its yellow candle-flowers. / They had an efficiency, a great beauty, / and were extravagant, like torture.”

Her fiercely alive, hawk-eyed subjectivity shines out in this not as part of disorder, but as part of who she was, in and out of states of ordinary consciousness. She made observations on starfish and McCarthyism, spring fashions and sex, from her earliest diaries to her most explosive poetry.

The same woman who observes the world closing round her like a trap, the horror of psychosis and depression, of reality warping itself upon her like a wire, is the same one who wrote pithy, tumbled-out, quick-eyed observations for Mademoiselle. It is still her, observing sharply, and accounting for it, even in the far territories of the conscious world. Somehow, the essential self keeps intact. And the razored accounting-for brings an outsider at least somewhat closer to understanding those other states, states of disintegration, of utter divorce, as well as states of transcendence. The scope of human experience is made a little wider, and thus our understanding of what it is to be human. Crucially, always, it is the human being at the center of the art that endures, that moves.

The stakes cannot be overstated. As often as utterance is heard it is not, or is misinterpreted, and the person at the other end, crying out, is forsaken. To be precise, to be compelling, to snatch and hold the attention, the sight, the ear, even for a moment, of another person, can be a battle for survival. I am haunted all the time by the stories I could not tell, the things that couldn’t be said, and the people I have known who have gone unheard. No utterance should be too humble, but the world, too often, decides otherwise.

Sometimes the story is so small and simple it breaks the heart. Emma Hauck, a thirty-year-old mother and wife, was admitted to the psychiatric hospital of the University of Heidelberg in Germany in February 1909. She was diagnosed with dementia praecox, now known as schizophrenia. Eventually, her illness was deemed chronic, “unheilbar,” and she was transferred to Wiesloch Asylum, where she died eleven years later.

The same year she was admitted, doctors at the University of Heidelberg set out to collect art created by people suffering from some sort of mental illness. The collection they assembled came to be known as the Prinzhorn Collection, after Hans Prinzhorn, the first director of the program. They collected some five thousand items, and the collection tours the world to this day. One of the most famous parts of the exhibition, and one that is frequently referred to by visitors to the exhibition as “profoundly moving,” “heartbreaking,” “haunting,” is an alcove containing letters.

Hauck’s letters, contained in this part of the collection, are sometimes so thickly crowded with words that they are illegible, parts of the paper plain gray where the words disappear into each other. They are the same words, written again and again, the same phrase, “Herzenschatzi komm,” hundreds of thousands of times: “Sweetheart, come.”

They were written by Hauck to her husband, Mark, who in the records was noted as “absent.” And they were never sent. They had been found in the archives of the University of Heidelberg and added to the Prinzhorn Collection. Some of the letters read simply, “komm, komm, komm.” Come, come, come. According to hospital records, she asked after her family relentlessly.

Was Hauck going unheard the fault of the concept of “art brut” itself? “Outsider art”? By saying, “This is outside of me, my experience, my humanity,” is that where we decide to no longer listen, to deny someone a chance to exist as a person? Instead of a woman removed from her loved ones, she is a madwoman, incurable, creating a piece of “art brut” that is, in Prinzhorn’s words, “the nearest to zero point on the scale of composition.”

The letters were never sent. Sometimes, there is a pane of glass so thick between speaking and understanding, between the human search for words and the listening ear. One person, in their commentary on the letters, describes their visual composition, as one would a painting, and adds that they are “not really designed for correspondence.”

The stakes are so high. Every brilliance must be employed, every ounce of skill and art. Because often we know the cost of being too humble in our pleading, of the jaw wired shut to the same repeated words, desperate. Other times, if we are lucky, someone will listen, will find a dictionary, catch that call for response, and recognize the tree by its leaf, however small.