The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: Edward P. Jones and the Other Side of Capitol Hill

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a continuation of a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

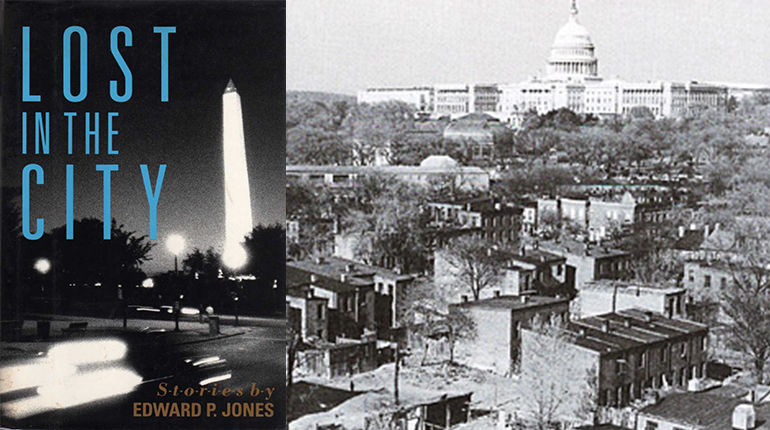

The writing of Edward P. Jones is often referred to as deceptively simple–subtle in its impact, a raw and minimalist portrait of life in our nation’s district. While these assessments are not unreasonable, they do seem to reduce his work to snapshots of quotidian occurrences in Washington, D.C. while rushing past his stories’ bold commentary on race, politics, and inequality as it relates to education and income.

Jones’ 1992 short story collection Lost In The City shows the writer using the fabric of his youth spent in the District of Columbia as the material with which he fashions a quilt of universal experiences. Never heavy-handed but also unafraid, these stories follow various characters—some recurring, some not—through life in working-class parts of the segregated city. Because of his childhood spent in D.C. in the 1950s and 1960s, Jones’ stories are disarmingly intimate, and authentically so. It is clear that he writes what he knows, and he knows his hometown well.

In “The First Day,” one of the most widely-read stories in his Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award-winning collection, Jones proves his expertise on D.C. in the first sentence, giving us details like his characters setting off down “New Jersey Avenue” that only a local could invoke. Granted, a non-local visitor could remember a state-named street such as that one too, but because he starts the sentence noting that this day is “an otherwise unremarkable September morning” it follows that he probably knows how a remarkable morning in this city is different. Imagine D.C. simply as a map, and Jones’ writing its literary key; by following his careful musings on the many circles of the city, one understands which path to best take.

But this writer of place doesn’t only tell his readers where to go, he tells us what wherever we end up will look and feel like too. Jones’ position as a black man from a working-class family in the city on which he writes might be the first clue that his characters are African-Americans, living in vastly different conditions than their white and white-collar counterparts. But the second clue is Jones’ treatment of culture. Consider details like his anonymous narrator noting, “My mother has uncharacteristically spent nearly an hour on my hair that morning, plaiting and replaiting so that now my scalp tingles. Whenever I turn my head quickly, my nose fills with the faint smell of Dixie Peach hair grease.” The tradition of a mother plaiting her daughter’s hair is a subtle and central aspect to black culture. Further, Jones touches on his own mother’s Virginian roots by choosing to decorate the narrator’s scalp with “Dixie Peach” hair grease, a nod to the even more aggressively segregated American south.

This recognition of the past and how it kisses Jones’ present-day is reflected in his change in tense, so slight it mirrors a magician’s trick. And Jones turns the reader’s gaze toward the future as well: the story begins in the present-tense but further down in the opening paragraph, following the young narrator’s hair being done, she reports that “shoes are my greatest joy, black patent-leather miracles, and when one is nicked at the toe later that morning in class, my heart will break.” These acknowledgments of time, made evident through his reliable narrator’s unreliable tenses, brilliantly acknowledge the setting of his story. As America’s home for all things political, Washington, D.C. demands that we reflect on the history of this country, while presently maintaining tradition, with an interest in the future. This undertone of past, present, and future moves beneath the city like the Metro, weaving the marble of monuments with the architecture of amendments, leaving neighborhoods like Jones’ behind all the while.

This is revealed when Jones’ narrator and her mother embark on the narrator’s very first day of school, and she is denied access to an elementary school with presumably more resources than the one her neighborhood offers.

. . . my mother tells her that we live at 1227 New Jersey Avenue, the woman first seems to be picturing in her head where we live. Then she shakes her head and says that we are at the wrong school, that we should be at Walker-Jones. My mother shakes her head vigorously. ‘I want her to go here,’ my mother says. ‘If I’da wanted her someplace else, I’da took her there.’ . . . For as many Sundays as I can remember, perhaps even Sundays when I was in her womb, my mother has pointed across I Street to Seaton as we come and go to Mt. Carmel. ‘You gonna go there and learn about the whole world.’

Here we see the narrator’s mother associating location in D.C. with opportunity. And just like that, Jones makes the universality of enrolling in school local—an inward turning of the world his stories often display. Upon entering her mother’s less-preferred school, the narrator admits: “Strewn about the floor are dozens and dozens of pieces of white paper, and people are walking over them without any thought of picking them up. And seeing this lack of concern, I am all of a sudden afraid.” Though seemingly insignificant, the young narrator embarking on her first day of school ever is disquieted by the unruly presence of something that is the very axis on which early education turns. Paper, as a foundation for her learning, is neglected; and in an adult cognitive leap, she understands that her education likely will be too.

Edward P. Jones does not represent the D.C. of the mainstream—no national monuments perforating his setting, no overt commentary on policy, no presidential-brand elitism lacing his words. Instead, he simply writes the life of the local everyman and pushes anything beyond that into the background, making excess as distant and flat as a souvenir postcard.