The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: The Power of Repeated Setting and Statement in August Wilson’s “Pittsburgh Cycle”

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a continuation of a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

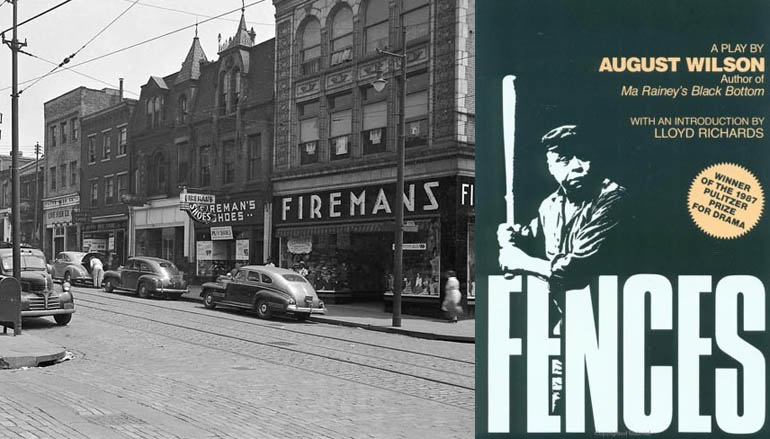

As we have seen, a host of writers in the American literary canon choose to settle on a location (which is usually their hometown) to set various unrelated texts of theirs against. In the case of August Wilson, playwright and Pittsburgh native, his hometown was the setting for nine of his ten plays; his complete oeuvre thus earning the moniker “The Pittsburgh Cycle.” Wilson’s alternatively named “Century Cycle” is unique in its scope: each play is set in a different decade of the twentieth century, allowing Wilson to examine the black experience through his characters across different times, but in the same place. This centralizes his work without making it narrow. By zooming in on Pittsburgh’s Hill District yet shifting the environment of his plays based on the changing sociopolitical interests of the time, Wilson makes the specific universal.

Born in 1945 to an African American mother and a German immigrant father, August Wilson spent his childhood in Pennsylvania in a decidedly working-class neighborhood, largely inhabited by black Americans and Jewish immigrants. To be sure, this experience inspired his commitment to turning a sympathetic lens toward those who were rarely seen, and heard even less. And though, as we know, all literature provides its audience with structures of imagery and voice, Wilson was more concerned with making the bodies and experiences of black Americans literal through his use of plays as a medium. This choice to lift his texts off the page and onto the stage felt both necessary and tactful; a way to force blackness into the spotlight, if you will. Even further, it provided an opportunity to bring life to the racism that the American people tried so assiduously to de-legitimize as mythology. Wilson’s ten-play cycle used the consistency of a region, marred with neglect but also the beauty of black dynamism, to turn a mirror to his audience sitting just beyond the fourth wall. From his first installment Gem of the Ocean to the final play Radio Golf, it is as if Wilson asks the same question, ten different ways: how can we, the American people, confront the gulf between us—a gulf made deeper by environmental distance?

In fact, Wilson basically said as much in a 1999 interview with the Paris Review:

I think my plays offer [white Americans] a different way to look at black Americans. For instance, in Fences they see a garbage man, a person they don’t really look at, although they see a garbage man every day. By looking at Troy’s life, white people find out that the content of this black garbage man’s life is affected by the same things—love, honor, beauty, betrayal, duty. Recognizing that these things are as much part of his life as theirs can affect how they think about and deal with black people in their lives.

Wilson uses Pittsburgh as a setting—one he knows well—so that he can authentically depict the nuances of this environment, to show his audience how problems on the micro level can quickly become macro if left unchecked. In an effort to check the racial hostility that punctuated his youth (in instances like having bricks thrown at his family’s home upon moving to a predominately white neighborhood), Wilson turned to the theater so that everyone could be a part of the conversation and work on the solution together.

In the same Paris Review interview mentioned above, Wilson explains this choice:

I think it was the ability of the theater to communicate ideas and extol virtues that drew me to it. And also I was, and remain, fascinated by the idea of an audience as a community of people who gather willingly to bear witness. A novelist writes a novel and people read it. But reading is a solitary act. While it may elicit a varied and personal response, the communal nature of the audience is like having five hundred people read your novel and respond to it at the same time.

Though Wilson’s plays are distinct in terms of plot, characters, and decade, two things are shared between them all: setting and theme. What was admittedly viewed as a lack of imagination by a younger me watching his plays, I now understand to be the brilliance of consistent conviction. The repetition of Pittsburgh is ultimately the repetition of August Wilson’s statement: until our American environment changes, our criticism of its stagnancy won’t either.