The Maternal Gothic and Maternal Ambition

In an early scene of Julia Fine’s The Upstairs House, the protagonist, Megan, lies in a hospital bed struggling to breastfeed her newborn. She notes the chasm between her experiences and her expectations, which were shaped by what “all the books claimed.” She refers to the author of the most well-known of these books as “Mrs. What-to-Expect.” Like Megan, while pregnant with my first child, I read many books on pregnancy and parenting. Chafing at Mrs. What-to-Expect’s book, objecting to its chirpy tone, cisheteronormativity, white, middle-class assumptions, and patronizing language felt like a pregnancy rite of passage; when I sought something less instructional, I read memoirs of early motherhood by writers I admired. What I took from these works, depicting parenthood with all the earned insight, lyrical grace, and metaphorical resonance afforded by retrospection, was the hope that it was possible to keep writing even after becoming a mother, possible to write about parenting in ways that transcended sentimentality.

Now in my second pregnancy, I am turning to fiction, in particular a spate of recently published novels that portray the challenges of the postpartum period and early motherhood, to make sense of my attempts to hold together the identities of writer and mother.

In Fine’s novel, out earlier this year, Megan’s postpartum recovery is disturbed by two ghosts who are figures in her abandoned dissertation on mid-century children’s literature. Though not a ghost story, Makenna Goodman’s The Shame (2020) also borrows elements from the maternal gothic in its depiction of Alma, a mother of two young children who is haunted by her obsession with a mom influencer on social media, an obsession that’s fueled by her own artistic and literary aspirations. While reading these grim, suspenseful novels in quick succession, I became disquieted by the gothic mode’s ascendancy at representing the challenges of early motherhood, especially for women who desire to nurture young children while producing ambitious academic and creative work. In other words, I wondered, what is it that’s haunting about mothers who want?

*

Several years after getting married, we were standing in the kitchen of my husband’s childhood home. I’d brought a salad to supper, and I’d just placed the bowl on the counter when my husband announced that I had “some big news to share.” My mother-in-law, bless her, raised her hands from the kitchen sink in celebration. “You’re pregnant!” she exclaimed, drying off her hands on her apron and stepping toward me in embrace. It’s here my memory short circuits. I can’t remember if it was my husband or me who offered a corrective, rushing into the gap between her arms and mine to explain that I’d just received an acceptance letter to a fully-funded MFA program.

I don’t fault my mother-in-law, and together we celebrated my news. But the reaction underscored a debate that had already filled more than a few pages in my notebook: could I become a mother, even as I sought to become a writer?

Around this time, I assembled a syllabus of sorts, immersing myself in the discourse on writing and motherhood. I started with Elif Shafak’s Black Milk: On the Conflicting Demands of Writing, Creativity, and Motherhood (2007). In this memoir about Shafak’s decision to become a mother and her subsequent experience with postpartum depression, Shafak narrativizes her internal monologue by transforming it into a conversation with cleverly named characters who represent various parts of her identity. She refers to these women alternately as her “finger women,” Thumbelinas, and the harem within. Though Shafak contains multitudes, I was most interested in the confrontations between Milady Ambitious Chekhovian and Mama Rice Pudding. Shafak also converses about motherhood and writing with prominent female literary figures by engaging with their writings; in turn, Shafak became one of my own conversation partners.

During graduate school, I developed the habit of looking to the final line of author bios to determine which women writers we studied had children. I sought out author interviews that might surface additional clues. Could I piece together a timeline of birthdates and book publications to determine how these writers managed to make it work? I took the clickbait each time a newly published article on writing and motherhood showed up in my newsfeed. These headlines often pursued absurd inquiries—What exactly is the ideal number of children for a woman who writes?—and sometimes disparaged altogether attempts to make motherhood the subject of literary work. Articles like these added to my handwringing, even though I recognized that the discourse on writing and motherhood only amplifies our cultural anxieties over whether it’s possible for women to pursue both career and motherhood.

Near the end of my MFA program, the decision began to feel more urgent. I went on a walk with an older friend, a woman in her seventies who is an artist and mother and has become a mentor to me. I remember laying it out to her like this: “It’s like I can have three things but only two of them at once: creative writing, employment, and motherhood.” Always a source of support, she asked the questions I needed to answer in order to hear myself more clearly, and she bore witness to my hopes and fears. As our conversation came to a close, she remarked on the privileged position I found myself in: the privilege to choose.

I held several part-time jobs in the year following graduate school, and eventually found an adjunct teaching position. Though I read compulsively and wrote often, I struggled to finish creative work in my non-working hours and published infrequently. I knew that if we were to conceive, my writing practice would be pushed even further to the margins of my life. And yet, my husband had landed a good job with benefits, we’d bought a house, and whether fears about my biological clock were founded or not, I felt them. Surrounded by college students on the bus to and from campus, I listened to podcasts and welcomed other voices into my internal monologue. I was as grateful to hear from women who were childfree, by choice or by circumstance, as I was to hear from women who were mothers. I found solace in Dear Sugar‘s advice to a forty-one-year-old man undecided about having children:

What didn’t I write because I was catching my children at the bottoms of slides and spotting them as they balanced along the tops of low brick walls and pushing them endlessly in swings? What did I write because I did? . . . I’ll never know and neither will you of the life you don’t choose. We’ll only know that whatever that sister life was, it was important and beautiful and not ours. It was the ghost ship that didn’t carry us. There’s nothing to do but salute it from the shore.

In the end, I chose to become a mother because of desire: it was the life I most wanted. As I squinted at the two pink lines of a positive at-home pregnancy test, I knew it was the rightest, truest decision I’d ever made. Within hours, I did the most responsible thing I could think to do and requested the library’s copy of What to Expect When You’re Expecting. Several days, and several reassuringly positive pregnancy tests later, I retrieved the bestselling book from the hold shelf and surreptitiously toted it home.

When it came to the conflicting demands of writing and motherhood, I didn’t expect it to be easy, but I was determined to make it work. I would not sacrifice my ambitions, nor would I let myself be haunted by a ghost ship.

*

While reading Fine’s The Upstairs House, with its narrative focus on Megan in the hours, days, and weeks after giving birth to her daughter, Clara, I found myself reliving my own postpartum experiences, including the transformative shifts in identity brought on by motherhood. While I did not face postpartum mental health challenges like Megan, I was moved by how realistically the novel depicts in tender, sometimes excruciating, detail the bewilderment of the fourth trimester—the physical pain and emotional intensity of healing from childbirth and learning to care for a newborn all while undergoing the complex transitional phase known as matresence, the process of becoming a mother.

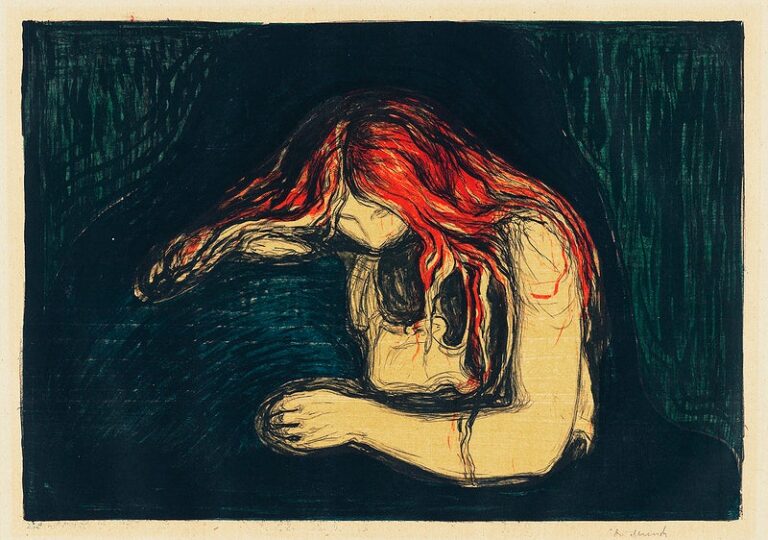

If my body was remembering the deeply satisfying warmth and weight of my daughter curled on my chest in skin-to-skin contact as well as the exhaustion of sleep deprivation and the ache and frustration of struggling to breastfeed, my mind was tracing the novel’s lineage back to Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein, not least because of the way reading Fine’s novel was an embodied experience. With Frankenstein, Shelley aimed to make a physical impact on the reader, to “curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart.” While reading Fine’s novel, I felt the physical and emotional overwhelm of the postpartum period even as my blood volume was doubling while I awaited my second child’s quickening and longed to feel evidence of the life that was taking shape within me. In the meantime, perhaps because I sought a way to safely confront my anticipatory anxieties about experiencing the fourth trimester for a second time, I was all too willing to give myself over to a ghost story.

In Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein gives life to an unnamed monster he constructs from the assembled body parts of deceased people in what he calls his “workshop of filthy creation.” In The Upstairs House, Megan’s husband, Ben, compares the efficiency of the maternity ward to a “baby factory.” Megan imagines a macabre scene of “little baby parts on a conveyor belt,” calling to mind Shelley’s description of Frankenstein’s laboratory and experiments. Megan ultimately concludes, “But I found comfort in the thought of each little part of Clara pieced thoughtfully together, of Clara as one of many, which made me one of many, which kept me safe.” Despite the disturbing imagery, I was pulled toward the safety Megan feels on the maternity ward where she is surrounded by so many other mothers, in stark contrast to the isolation that will threaten her upon bringing Clara home. For me, reading maternal gothic novels gives me the experience of being one of many. I find a sense of comfort and safety in the stories of other mothers even despite the fear I encounter in the pages.

The Upstairs House takes up the traumas and isolation of the postpartum period, and in doing so, it begins with a death, not a birth. From the preface to the first chapter, from hospital room to hospital room, the novel’s opening images are a reminder of what’s become too commonplace a theme and yet is central to the maternal gothic novel: the tension between death and procreation.

The preface is brief, two pages. It’s November 1950 and Michael Strange—the American poet, playwright, and actress—lays dying in a hospital bed. Sitting vigil is Margaret Wise Brown, author of the children’s classic Goodnight Moon and Strange’s lover, though their relationship was often volatile. Strange speculates that her spirit is irrevocably bound to her creative work and wonders if Brown will succeed at summoning her from the grave by reciting her poetry. “After all,” she says, “that is the spirit: in ink, in the poetry. That is the soul.”

Then, it’s October 2017. A smiling mylar balloon presses against the window of a thirtieth-floor hospital room where Megan is recovering from giving birth. To her, the balloon is sinister, mocking. Her mother and husband seem not to notice the balloon and dismiss her concerns altogether. The balloon’s presence unsettles the reader. It’s the first of many discrepancies between Megan’s perception of reality and everyone else’s. Megan’s experiences point to how women are socialized to doubt themselves, the myriad ways our culture dismisses women when they tell the truth about their experiences, as well as the tragic consequences of that doubt and dismissal.

That Fine writes in the mode of gothic horror conveys the gravity of the risks pregnant people bear, risks to health and well-being that are exacerbated by the inadequate care and support pregnant people receive in this country. Though gothic novels often engage the surreal, fear for maternal well-being remains all too real. Over the course of my first pregnancy, ProPublica and NPR published an investigative reporting series with an appropriately gothic title, Lost Mothers. It found that the United States is the most dangerous developed country in which to give birth, due to its high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity, in addition to the systemic racism that drives racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health outcomes. Unsurprisingly, even less attention is given to postpartum mental health. From pre-conception to postpartum care, transgender and non-binary parents are often excluded from these conversations altogether. With no federally mandated paid parental leave, one in four birthing people returns to work just two weeks after giving birth. Those who are able to take parental leave often find themselves isolated and overwhelmed.

By the novel’s end, Megan is diagnosed with postpartum psychosis and hospitalized. Though The Upstairs House is deeply researched, I can’t say whether it succeeds at representing postpartum psychosis. What is clear to me, as a reader, is that Fine refuses to depict Megan as an unfit mother. Megan abandons her dissertation, but unlike Frankenstein, she refuses to abandon her child. Even when her actions place them both in danger, Megan’s love for Clara is never called into question.

In “Female Gothic: The Monster’s Mother,” Ellen Moers credits Shelley with being the first novelist to take up the mode of gothic horror in order to represent childbirth. Shelley’s innovation makes her a primary forebearer of contemporary maternal gothic novels. Although Victor Frankenstein is a male scientist, not a mother, and many have noted the novel’s subordinate women characters, Moers argues compellingly for reading Frankenstein as a birth myth—a mythology whose expansiveness underscores the risks pregnant people bear, the traumas of the postpartum period, and the intensity of the parent-newborn relationship. Moers writes, “Frankenstein seems to be distinctly a woman’s mythmaking on the subject of birth precisely because its emphasis is not upon what precedes birth, not upon birth itself, but upon what follows birth: the trauma of the after-birth.”

After giving birth, the ghosts of Strange and Brown begin to haunt Megan, as does her suspended academic career. By the time Clara is ten days old, Megan’s husband has already left town for a week-long business trip. In his absence, Megan struggles to care for herself while she tends to Clara. She dreams about her graduate school cohort and feels guilty about her abandoned dissertation. Like Strange, Megan, feels her legacy is in ink. She imagines what her tombstone would say if she were to suffer an early death: “Megan Weiler, survived by sixty unwritten pages and a round or two of revision. Also a baby.” This specter of unfinished business is the threat that motivates her to strap on her breast pump at the kitchen table and open her laptop. She rereads a section of her dissertation but can’t quite find her way back into the writing, and even the breast milk she manages to produce ends up spilled on the kitchen floor.

I felt in my body the agony over the spilled breast milk, just as I felt Megan’s desire to write. My daughter was eleven days old when I picked up my notebook again. In it, I record the lightning storm of static I set off each time I parted my robe in the dark for a nighttime feeding. I note that I choked up over the newness of the phrase “my daughter” while on the phone with our doctor’s receptionist, that I felt waves of anxiety each night as bedtime approached, and that I was stunned at how fragile everything seemed. Like Megan, I was on maternity leave, unpaid but fortunate enough to be supported by my partner, but I needed to feel myself write, desperate to prove to myself that some part of the old me remained. I was still mostly who I had been, but I was also entirely changed by the intensity of what I felt for my daughter.

When I read the final journal entry of my pregnancy, I’m surprised to find that what worried me most wasn’t fear of childbirth, but of motherhood’s impact on my writing. “Lately I have been a writing teacher and a writing conference planner, but not so much a writer,” I wrote. “I’m worried about the addition of mothering to my responsibilities.” I feared losing what felt like an essential part of myself. The last words I wrote prior to giving birth were a promise to myself: “I will mother and write, write and mother.”

In the end, Megan does not return to her dissertation. She concludes, “The fantasy I’d entertained in the throes of my ‘flight of ideas,’ of having both motherhood and a career, was a pipe dream.” I’m disappointed in this ending, though it feels inevitable given the lack of support she receives from her husband, her mother, and even her dissertation advisor. Even so, Fine gives life to Megan’s body of work, publishing excerpts of her dissertation throughout the novel. In an interview, Fine explains that the inclusion of the dissertation solved for the expository passages about Brown and Strange she felt were needed. But in my reading of the novel, it also makes it a bit Frankensteinian in structure, an amalgamation of parts, Megan’s spirit in ink that refuses to die.

*

Although it engages few overt elements of horror, Makenna Goodman’s The Shame suspensefully incorporates many of the maternal gothic’s themes, namely the confinement of domestic settings, the conflicting demands placed on mothers, and the taboos of motherhood. Throughout, the novel’s protagonist, Alma, expresses the embodied fear, as well as the embodied love, that accompanies motherhood.

It begins with a riddle. If you were standing on a shoebox-sized island in Vermont surrounded by hot lava but sustained by a lifetime supply of undercooked egg whites, would you stay or would you risk the miles-long journey to a lush oasis offering an all-you-can-eat buffet of delights. The point is this: would you escape the prospect of a “long and unhappy life”? If so, how? The riddle’s metaphoric value is never directly explained, nor is the riddle mentioned again. But Alma introduces herself to the reader by sketching out her cartoonishly violent solution to it, which involves a gun and the corpses of migratory geese as stepping stones. In the next scene, she is free. She has escaped the isolation of the Vermont homestead she shares with her husband and two young children. She is driving the family car unencumbered, under cover of darkness toward an unknown destination, and thus sets into motion what makes the novel’s central tension. Alma has left home just as she is on the cusp of realizing her dream of publishing a book. But why?

Reading this novel while parenting a toddler and working two part-time jobs during a pandemic that upended my child care arrangements and made our nuclear family structure feel all the more isolating, I was surprised to find myself fantasizing about Alma’s descriptions of life on her homestead. It’s clear that Alma is isolated and bored, but rather than undercooked egg whites, the tedium of her daily doings seemed like an all-you-can-eat buffet of delights compared to the tedium of my own. I was envious, too, of Alma’s big break, which comes in the form of a book deal with a toy company that commissions her to write and illustrate a picture book about two popular animal figures. So I saw myself in Alma—not in her working, but in her wanting—when she admits to her practice of lying awake at night imagining alternative scenarios for herself. “Usually this new life is a direct response to someone I’ve just met or heard about, after I’ve expertly idealized their reality as far more interesting than mine,” Alma reflects. These alternative scenarios aren’t so much ghost ships she long ago chose not to board, but they are mirages, lush oases that shimmer in the distance making false promises of a long and happy life.

If I identified with Alma’s desires, I also identified with her fears, of which she has many. Early on in the novel, she shares a drafted letter she revises frequently, a letter intended for her children to read in the event of her untimely death. She worries about her children experiencing a school shooting and about raising a school shooter. She worries about her children learning to drive and calculates the probability of one of her two children dying in childhood. She worries her children don’t love her, but are merely addicted to her comforting presence. She worries about failing as a mother, failing as an artist, failing to become someone of value.

What I’m beginning to suspect about the maternal gothic is that when it comes to writing about motherhood, perhaps alongside the monstrous, the mundane is more compelling, the miraculous more believable. Goodman’s novel manages to capture the complexity of motherhood, the difficulties and delights that are somehow both entirely ordinary and also profoundly existential. I still fear for my creative work, but what haunts me most now is the thought of life without my daughter, life without the child I carry in my womb. I shudder when I see that ghost ship carrying the childfree me sail by, and I’m glad to see it pass.

Alma’s expression of maternal dread places The Shame in the tradition of the maternal gothic, but the most gothic feature of the novel appears in response to Alma’s ambitions in the form of the parasocial relationship she creates with Celeste. In addition to the never-ending demands of homesteading and parenting young children, Alma nurtures artistic and literary aspirations. Creativity is tied to her identity and an escape from the home life she sometimes describes as a prison, an island, domestic entrapment. “At this point, I was being stretched to my limit when it came to mothering. I tried to access a feeling of selfhood from small bouts of writing, daydreaming and painting,” she narrates. As a novel project she’s working on takes shape, she begins to search for an Artist, with a capital A, to serve as a model for her protagonist, Celeste. Alma’s proclivity to idealize other mothers’ lives leads her to social media, and there she finds the Brooklyn-based ceramicist and mom influencer who becomes her Celeste. For Alma, Celeste is “the ‘me’ I might have become if I had learned to like myself.”

Celeste is a single mother of three with exquisite taste. She eats muesli with hemp milk for breakfast and carries a handcrafted leather handbag, practices yoga and Transcendental meditation, weans her children with cupcakes, and sings in a band on the weekends. Instead of making progress on her novel, Alma’s obsession with Celeste sends her to the grocery store to buy muesli that tastes like cardboard.

Like a ghost, Celeste haunts Alma. Alma describes her presence: “She began to wander into my daily consciousness before my morning coffee and late into my intimate hours.” Goodman’s depiction of Celeste reminds me of the figure Virginia Woolf referred to sardonically as “The Angel of the House.” In “Professions for Women,” a lecture-turned-essay about the challenges women writers confront in their work, Woolf describes the Angel who haunted her, interrupting her writing process, wasting her time with torments and urging her to charm, to flatter, to lie instead of writing what’s true. Woolf captures the Angel’s purity and graces, writing, “She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily.”

In order to write, Woolf must kill the ideal—here again the gothic paradox of death and creation—though she acknowledges that at times the Angel comes creeping back. She writes: “Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing . . . These were two of the adventures of my professional life. The first—killing the Angel in the House—I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. I doubt that any woman has solved it yet.” While I haven’t solved the problem of writing the body—and I appreciate that later in the essay, Woolf complicates the gender binary by admitting the difficulty in attempting to define what she means by woman—I wrestle with my own Angel of the House, who bids me to empty the dishwasher instead of opening my notebook.

To finish this essay, I’ve overlooked the clumps of dog hair on the carpet until my husband and toddler made a game of vacuuming it up, I’ve entertained my daughter with several Cocomelon episodes so I could write a paragraph or two more, I’ve ignored several work-related emails, and I’ve allowed our fig harvest to bruise on the counter instead of promptly canning them, risking fruit flies and rot. My Angel is part Proverbs 31 woman (an unwelcome holdover from my religious upbringing), part Montessori guide (nary a plastic toy in sight!), and part zero-waste activist (what goes better with mom guilt than climate guilt?). Like an undead creature, my Angel visits me whenever I open Instagram.

Over the course of the novel, it becomes clear that Alma has left the confines of her homestead for New York City to meet with Celeste, with whom she has been in contact under the pretense of interviewing to be her nanny. (The irony, of course, is that even in her attempts to escape motherhood, she pursues another form of caregiving.) Alma drives into the night after a particularly nasty argument with her husband over her reluctance to sign the book contract with the toy company. She escapes the island of her homestead, fleeing in the direction of her fantasy life. When she arrives, Alma stalks Celeste until she collides with her, and in that collision, the ideal dies. She watches Celeste struggle with her stroller through the subway and notes the impatience with which Celeste speaks to her children: “Although Celeste tried to hide it, I could see that trapped feeling, that desire to work that was in deep conflict with the need to protect her children from a world without Mother.”

Alma drives home, all the while composing her children’s book about the raccoon and the owl. As she enters the house, her gaze lingers on the familiar sight of an angel affixed to her front porch. But this is no Angel of the House, this one is a gargoyle angel her friend sculpted of cow dung.

The novel’s final paragraphs render the bodily sensations of returning home, and emphasize in particular Alma’s renewed vision through several descriptive sentences that begin with “I could see . . .” And this phrase, too, concludes the novel: “I slipped off my boots . . . and turned on the mudroom light so I could see.” As a reader, I appreciated that Alma’s journey resulted in a shift in perception. But I also wanted to know if upon her return home, without the distracting presence of Celeste, Alma would complete her children’s book. Would she return to her novel draft? How would she resolve the “deep conflict” she projected onto Celeste: the conflict between the desire to work and the need to protect her children?

Even though I know that the challenges parents face in this country are systemic and intensified by racism and income inequality—as the primal screams of working parents recorded by the New York Times hotline during the pandemic have made resoundingly clear—I still feel my failures as an individual. I want to believe that a perspective shift is enough to square my desire to mother with my desire to write. That adopting some new time management strategy might balance the demands from my work as both primary caregiver and adjunct professor such that I might afford the time to produce more creative work.

I benefit from the privileges of my identity as a white, cisgender woman and the support of a partner committed to an equitable relationship and yet it still feels like an inescapable riddle. I’m realizing that I can’t overcome the Angel of the House alone, that it’s both important to take on the ideal of motherhood and that it’s not enough without systemic change, and perhaps that’s why I appreciate the companionship these novels afford. If it’s a riddle, perhaps it’s one that’s unsolvable without collective action.

*

Mothers who want are both haunted and haunting; they are threatened by the same power structures that they themselves threaten. In addition to their respective ghosts, both Megan and Alma are haunted by their own mothers’ desires, desires that, true to gothic form, make for absent mothers. Megan’s childhood was shadowed by her mother’s unrequited love for her father. After he had an affair with the babysitter and left to begin a new family, Megan’s mother struggled to accept her new reality, experienced a mental health crisis, and mostly left Megan and her sister to raise themselves. Likewise, Alma’s mother is a failed novelist who hired a nanny to raise her daughter so she could devote more time to her art.

Like these mothers, I often feel a bit monstrous when it comes to my aspirations—pieced together, an unwieldy patchwork of parts of myself, the undead parts of who I was before and the beating heart of who I am now after becoming a mother. I write to remember myself as both mother and writer and to prevent my unrealized ambitions from haunting my children. Sometimes that has meant composing an essay on the notes app of my phone while commuting to campus by bus or stealing away to a coffee shop on Saturday mornings to make progress on my novel or scribbling lines into a sauce-stained notebook while cooking dinner. Mostly it looks like rising zombie-like in the early hours of the morning, often after a night of interrupted sleep, to write. Alone in my overstuffed chair, I sit with my coffee and my notebook and write my morning pages, a ritual I rely on to nurture both my equanimity and my creativity. When my daughter emerges from her room each morning, I set down my notebook and we cuddle together under a blanket and she tells me about her dreams. And when she’s ready to begin playing, she climbs down and hands me my notebook and pen. My hands are always full.

So much of motherhood involves sweating while concealing the strain, the stain. Though the gothic mode succeeds at depicting the anxieties of motherhood, particularly those of white, middle-class mothers, as well as critiquing the power structures that reproduce them, one of the maternal gothic’s limitations is the genre’s failure to cast an alternative vision for the possibilities of motherhood.

Perhaps the maternal gothic’s vision problem is where Shelley’s Frankenstein may also prove instructive. Not only was the novel an early example of the female gothic, it also was an early work of what would become the genre of science fiction. And it’s in the yet-to-be-created worlds of speculative fiction where my liberatory imagination has been most nurtured.

After writing of vanquishing her Angel of the House, Woolf concludes her essay with a series of questions:

You have won rooms of your own in the house hitherto exclusively owned by men. . . But this freedom is only a beginning—the room is your own, but it is still bare. It has to be furnished; it has to be decorated; it has to be shared. How are you going to furnish it, how are you going to decorate it? With whom are you going to share it, and upon what terms?

These are questions of imagination.

At the time of Shelley’s writing, pregnant women were warned to protect their imaginations, cautioned that their thoughts and feelings could transform their growing fetus. Monstrous imaginations could reproduce monstrous beings. Though I don’t believe that reading gothic horror while pregnant will threaten the well-being of the child I’m carrying, my greatest hope is that through my mothering and my writing I might pass on to my children a more radically expansive imagination.

This piece was originally published on September 2, 2021.