The Modern-Day Myth of The Good Life

In the spring of 2014, as part of a program offered by my college, I and eleven other students moved to a biological field station nestled in the woods of western Illinois. We lived frugally in a converted barn outfitted with only basic necessities, the goal being to experience a different, more purposeful way of living. Having recently turned twenty, I craved what I believed to be an authentic experience. Social media platforms like Instagram were just starting to gain in popularity, and I was not yet accustomed to scrolling through feeds to peer into the well-lit lives of influencers. Still, I desired a picturesque life rooted in nature, believing it to be a freer, more grounded way of being. Back then, if I had read Helen and Scott Nearing’s famous book Living the Good Life about their homesteading experience in Vermont, I’m certain I would have wanted nothing more than to live a life like theirs. Even now, as a thirty-three-year-old woman with a husband and young son, when I read the words of the Nearings, I must constantly remind myself that as attractive as they make homesteading sound, everything is not always as it seems.

My time living at Green Oaks was relatively short. However, the impact those few spring months had on me has left an impression. The days there were long and expansive, filled with everything from bread making to prairie burns. I loved slipping on a pair of tall rainboots and making my way down from the house to Short Cut Trail, where I would almost immediately leave the path to wade through the winding creek that cut through the middle of the forest. From my vantage point the trees loomed high around me, and I felt an overwhelming sense of peace encircled by all that green. The natural world had called to me, and I had answered its call by agreeing to live out there in exchange for a few credits and a unique experience I could boast on future resumes. However, there has always been something about living there that nagged at the fringes of my consciousness and felt, at times, disingenuous.

Let me be clear. This Thoreau-esque return to nature truly was unique, and I have nothing but gratitude for my experiences out in those woods. But with only three months spent living in that house, it was impossible for us to truly establish a self-sufficient lifestyle (we were going home for summer vacation just as the growing season was getting started). Still, we devoted ourselves to learning about what it would take to make a life away from the buzz of the city. The things I experienced there—beekeeping, cutting wood, starting fires, foraging—were crucial skills for anyone looking to build a homestead, but because we were truly only a short drive away (i.e. thirty to forty minutes) from the comforts of campus, there were times when it felt like we were only playing at this new lifestyle (which, of course we were), and that we could return to our easier lives anytime we wanted (which, of course we could). Our decision to “live off the land” came with a pretty cushy safety net that was extremely easy to forget about once we established routines that, if they should fail, could be easily rectified with a lot of outside help and campus funding. We were genuine in our desires, certainly. But our desires were always just that: yearnings rooted in want rather than need.

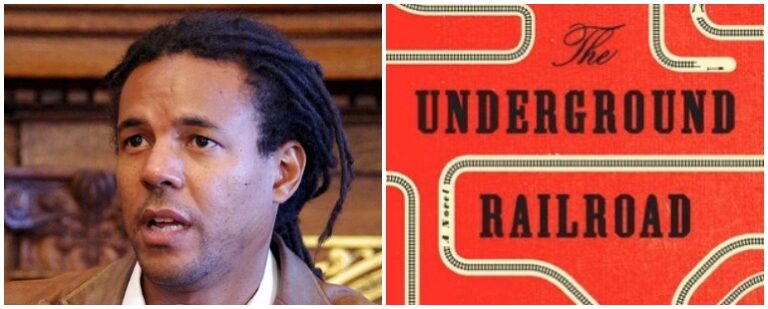

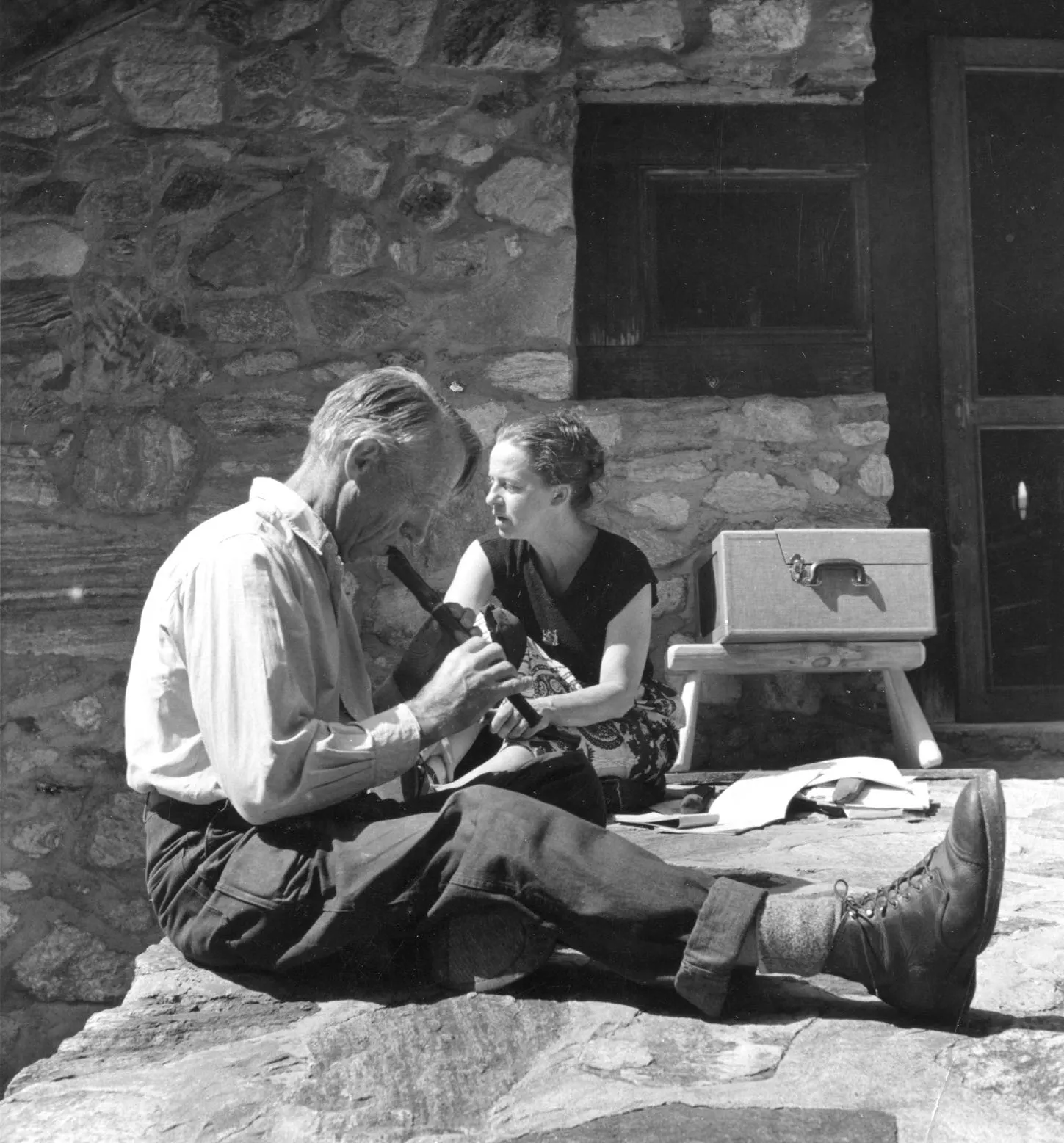

In the 1930s, Helen and Scott Nearing began their first homestead. They purchased a plot of land in Vermont for around $1100 (which would be closer to $27,000 today) and began their journey. The main house they lived in was built by their own hands from stone found near and around their property. They cultivated vast, fruitful gardens from which they cooked almost all their meals, and they did not own any livestock—a choice made by them to forgo using animals and their biproducts for food. Their house was warmed through the burning of wood, which they chopped and stored themselves, and their main source of income came from harvesting sap from maple trees and selling it. Their whole goal was to make just enough money to have their basic needs met so that they had time to pursue other, more intellectual pursuits. At the time of their deaths, Scott was one hundred years old, and Helen was 91.

Over time, the Nearings and their books have become bibles for anyone looking to live a simpler life, and when reading the very matter-of-fact passages in Living the Good Life, the Nearings make an extremely persuasive case for establishing a life with routines and rhythms more closely aligned with the natural world and its seasons. They also make this life sound easy, as if any setbacks you might encounter during your quest to build a house or dig a well are nothing more than slight hurdles, easily cleared so long as you know exactly what to do. Throughout the text, the couple constantly preaches their successes—almost to the point of boasting—so that by the time you are done reading the book, the decision to homestead feels like a no-brainer. Why wouldn’t you want to live a simpler, less expensive, healthier life that also wasn’t as reliant on a capitalist driven society? Perhaps you too could be living the good life, finally at peace with yourself and the world around you.

Living the Good Life is the first of two books that are now usually collected into one larger book titled The Good Life. While the first book details the Nearings’ life in Vermont, its sequel, Continuing the Good Life find the duo relocating their homestead to Maine where they lived for the rest of their lives. There are many criticisms that have come up about the Nearings and their lifestyle over the decades, not least of which is just how believable it was for them to have succeeded on only the selling of maple sap alone. If you are someone who takes everything at face value, reading Living the Good Life would have you believe this is exactly what they did. However, a quick Google search will bring up any number of articles referencing the fact that the Nearings both came from well-off families, with each of them inheriting considerable amounts of money that afforded the couple a safety net should their attempts at a self-sufficient life fail. (Talk about pulling a “Henry David Thoreau.”) It is no surprise then, that at least for the Nearings, to live a “good life,” one has to have access to money.

Obviously the Nearings were not alive during the heyday of social media, but if they were, the downright chipper, can-do attitude put forth in their books is just the sort of thing that would translate beautifully to the smartphone screen. They are crafty with their language and careful to avoid talking about their troubles too harshly, creating a near-picturesque life where even hardships are doable. If the Nearings were the early pioneers of the popular “Back to the Land” movement that occurred in the ’70s, there is no doubt that their lifestyle and their message is still alive and well in certain social media circles with a focus on living a simple life. Hashtags like #slowliving and #homesteading have millions of posts designed to encourage people to embrace a more subdued lifestyle. Most of these people—who are usually white women—own chickens, milk cows, make their own butter, and spend a good deal of time cooking homemade meals in the kitchen. If these women happen to have children, they are almost always homeschooled, typically with alternative educations like Waldorf or Montessori. Their lives off the grid appear effortless and beautiful, as if they have easily slipped from between the pages of Little House on the Prairie, just with a slightly better skincare routine.

What makes these particular social media influencers so much like the Nearings is that both talk about the self-sufficient life as if it is something that is achievable to everyone. But what each of these people fail to say is that behind every “good life” is usually a whole lot of cash. This isn’t a new revelation by any means, but it does bring up important questions about authenticity and whether there really is such a thing as a self-sufficient life in our capitalist western society.

It should go without saying that I do not live on a homestead. My eggs still come from the store, and though I have learned how to make my own butter, the heavy cream necessary to do so has been purchased in the aisles of my local Trader Joe’s. I am, by no means, living a self-sufficient lifestyle. Last summer, I failed spectacularly at getting our brussels sprout plants to grow. Still, much like my twenty-year-old self, I feel the pull towards a simpler life. I want to fill mine and my family’s days with purposeful things, and I would be lying if I said there aren’t moments when I find myself buying in to the words of the Nearings and their modern-day influencer counterparts. Which is why it is always helpful for me to remember that while the photographs and videos of prize-worthy pies and fresh, homemade mozzarella (which, let’s be honest, I’m totally going to try to do), and the very fact that I’m able to peer into these people’s lives at all is proof that maybe things aren’t as easy or as simple as they actually seem.