The Narrative of Breast Cancer

When I was about ten, I noticed a placard that diagrammed at-home breast exams a woman could administer to herself hanging from the dial of my parents’ shower. It showed a woman with one arm up, the other rotating in circles first one way then another. At some point, someone—the placard?—told me that a little lumpiness in your breasts is normal, especially before menstruation, but that it was still important to regularly examine your breasts for anything that felt hard, like gravel, beneath the skin. In this way, breasts began to feel to me like ticking timebombs we buy cradles for at Victoria’s Secret.

Even when breast cancer doesn’t run in your family, it always seems that someone’s mother or grandmother has it, that someone is doing genetic testing to see if they have one of the known genetic mutations that increase the likelihood of developing it, that a colleague had it years ago, that a celebrity is making public declarations of how she is navigating treatment for it. Although all people have breast tissue and are at risk, women’s bodies feel marked from the beginning.

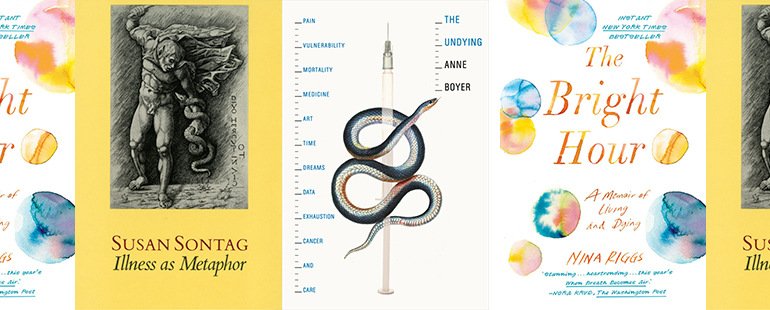

“Women with cancer are often forced to watch themselves dissolve, lamentable objects intolerable as lamenting ones, witnesses to everyone else’s sad stories but socially corrected as soon as a sadness issues from their own mouths,” the poet Anne Boyer writes in her recently published memoir The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care. In her examination of the restrictive nature of telling a cancer story in our culture, particularly when it is a cancer as gendered—feminized—as the one, breast cancer, she had, she notes, “Cancer is in our time and place one of the most effective diseases at eradicating the precise and individual nature of anyone who has it.” Boyer joins others, like Susan Sontag, Nina Riggs, Audre Lorde, and Kathy Acker, who push against and question the breast cancer narrative conventions.

Boyer observes that in our culture, “to tell the story of one’s own breast cancer is supposed to be to tell a story of ‘surviving’ via neoliberal self-management—the narrative is of the atomized individual done right, self-examined and mammogramed, of disease cured with compliance, 5K runs, organic green smoothies, and positive thought.” These are the restrictive conventions of the idealistic—and simplistic—cancer story that marginalize or fail to allow for alternative ways of storytelling that might upset the favored cancer ideology. “I do not want to tell the story of cancer in the way that I have been taught to tell it,” Boyer declares, invoking the stereotyped breast cancer survivor. “[I]f she is allowed a voice, she can complain in fractured and enigmatic drips or corral situational cliché and/or made-for-TV sentimentality and/or patho-pornography into a good story. Literature sails along on every existing prejudice.” The ugly, expensive side of cancer is hidden, especially if you are a single woman, as Boyer is, or if you are disabled, living in poverty, a person of color, or otherwise marginalized.

Inherent in a woman’s decision to alternatively narrate the experience of breast cancer is determining what pronoun to use given to what extent one’s view of one’s self has irrevocably changed: “a diagnosed person is liberated from what she once thought of as herself,” Boyer says. While the obvious choice might be the first person singular, this pronoun is fraught with both limitations and even erasure. “Breast cancer exists uneasily with the ‘I’ that might ‘speak of this terrible business’ and give ‘this miserable account,’” Sontag asserts in Illness as Metaphor. “This ‘I’ is sometimes annihilated by cancer, but sometimes preemptively annihilated by the person it represents, either by suicide or by an authorial stubbornness that does not permit ‘I’ and ‘cancer’ to be joined in one unit of thought.” One desires, then, to dissociate, referencing the body as separate from oneself via the third person or by adopting the second person to observe oneself from a distance. At other times, the first person plural can be used to encompass this experience that many women share.

“The boundaries of our bodies break,” Boyer explains. “Everything we were supposed to keep inside of us now seems to fall out. Blood from chemotherapy-induced nosebleeds drips on the sheets, the paperwork, the CVS receipts, the library books. We can’t stop crying. We emit foul odors. We throw up…We do not look like people: we look like people with cancer. We resemble a disease before we resemble ourselves.” In her memoir The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying, the late Nina Riggs sits in the waiting room for her radiation treatment and observes, “These days, these are my people—the Feeling Pretty Poorlies…We’re kind of disheveled. We’re often asymmetrical. We’re wearing comfortable pants and bright scarves. We tend to either smile too quickly or not at all.” Riggs shares cancer with her mother, who fought it for eight years before dying not long before Riggs did; with a close friend; with the very young woman she notices with mastectomy drainage bags clipped to her shirt. Riggs’s “we” is both immediate and extended to the “we” Boyer embraces.

While there’s safety, comfort, and recognition in “we,” both Boyer and Riggs seek “you” in other moments. “Right before all your hair falls out, it aches,” Riggs writes. “Like a ponytail pulled back for too long. And even after it’s all gone, the ache resurfaces. You run your hands through the air, but assuage nothing.” Riggs’s pain, like her hair, is both presence and absence. Boyer describes, “Pull your hair out by the handfuls in socially distressing locations: Sephora, family court, Bank of America…Put your head out the window of the car and let the wind blow the hair off your head.” In her second round of chemo, Riggs is “noticeably patchier” between leaving her house and joining her family at a bar. Although their life circumstances may be different in many ways, there are still aspects of Riggs and Boyer’s illness—like the way in which they lose their hair—that become interchangeable, that situate them in a shared experience.

Cancer feels nearly inevitable, like a rite, in Riggs’s family, as do its treatment options. For Boyer, though, cancer is new territory untried by the generations before her, and she examines how debilitating treatment is on its own, as well as the cultural assumption that invasive and excruciating treatments are necessary measures. Boyer begins with the second person: “There is a choice, of course, and you make it, but the choice never really feels like yours. You comply out of a fear of disappointing others, a fear of being seen as deserving of your suffering, a hope that you could again feel healthy, a fear that you will be blamed for your own dying, a hope that you can put it all behind you, a fear of being named as the person who cannot cheerfully submit to every form of self-preservative self-destruction written in the popular instructions. You comply from ritual obedience.” Here, “you” could be anyone suddenly faced with “the terrible thing,” as Riggs calls it. The “you” sucks us into the terrible thing, making us both complicit in complying out fear and of putting pressure on the cancer patient, too. And then Boyer flips to the first person singular to explain the enormous environmental and monetary costs of chemo: “The cost of one chemotherapy infusion was more money than I had then earned in any year of my life.” Boyer eschews the pretty pink cancer ribbons and a victor’s triumph in favor of a realistic portrait of cancer’s cost: the debilitating effects of chemo she will always live with, having to exchange her mind for her life, environmental damage, and more. She may be victorious, but it’s a costly victory.

Both Boyer and Riggs dwell, too, on how breast cancer treatment—mastectomy, chemo, radiation, countless appointments—run parallel to their daily lives that have ceased to come to a halt. For example, both women have children to raise. “[A]fter treatment, when my body was wrecked, when my body was like a car with parts that kept falling off, when I failed at, as U.S. disability law calls it, ‘basic activities of daily living,’ I wondered how all those dollars had passed through my body and I was still left in such bad shape.” Riggs plays with group names, like a memory of elephants, to describe her experience navigating between sick life and ordinary life: “I train my eye on these dreamlike certainties: A cure of doctors will examine me in the morning. And in the meantime, a cauldron of thunderstorms simmers on the horizon and an anticipation of cocktails awaits some ice.” Boyer is counseled to hide her illness, and she teaches her courses fresh from a medical procedure, still in the fog of pain and medications. Riggs signs permission slips, buys poster board for her son’s school project, plans her mother’s memorial service. Life must continue until it doesn’t.

“Here we are, here I am, alone and myself, half of me fallen off, half of us gone, and all of us ghosts or the undying ones, half of us dead and half of myself nowhere to be remembered or to be found,” Boyer writes in the swirl of treatment, oscillating between the individual and the collective. She is kept alive but at great cost. She is telling a story stripped of glamour, a story she wants to hold at arms-length, staring in the mirror at a body so changed from the one she once checked for wrinkles. Riggs, the great-great-great-granddaughter of Ralph Waldo Emerson, turns to him for his title as well as to draw her into the collective. “That is morning,” Emerson writes in his journal in 1838, “to cease for a bright hour to be a prisoner of this sickly body, and to become as large as the World.” Boyer offers the world the grittiness of experience through her sick body: “[T]he truth must been written for someone,” she writes, “a someone who is all of us, all who exist in that push and pull of what bonds of love tie us to the earth and what suffering drives us from it.”