The Parallel Narrative Arc in Memorial

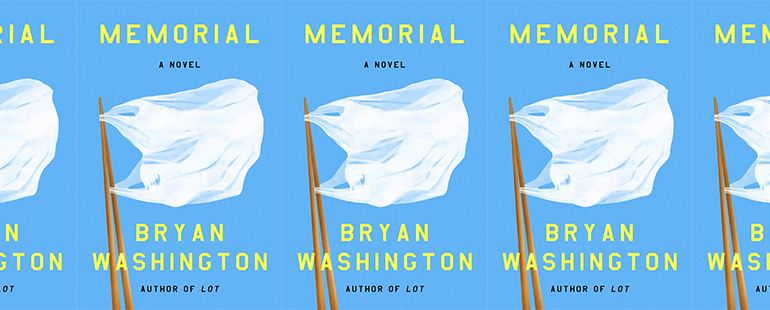

Bryan Washington’s beautiful and heartfelt novel Memorial, published last fall, explores the relationship between Benson and Mike, two young men who live together in Houston. Benson is a Black daycare worker, and Mike is a Japanese American chef; when we meet them, it is clear that their relationship of four years or so is faltering. Over the course of the novel, as the two men separate and reunite, eight black-and-white photographs appear alongside the text. Photographs in a novel are always a bit of a surprise; they cause the reader to consider the blurring of fiction and nonfiction, the way in which the real world is inserted into the fictive. Here, the photographs—which are attributed to Washington on the copyright page—are used, in part, to consider how we use images to communicate. In addition, they also work together to create a narrative arc that echoes the arc of the book itself.

The novel begins, from Benson’s point of view, as Mike leaves for Japan to find and care for his father at the same moment that his mother arrives for a visit in Houston. In their first contact after Mike is in Japan, he texts Benson a selfie from Osaka, at a train station, “the background clogged with bodies.” They text back and forth, then “Mike sends another selfie. There’s the backdrop of a neighborhood. It looks quiet, bookended by telephone poles.” The photo that follows this description is not, however, of Mike. It is of a narrow, empty alley, wires and lights overhead, their shadow on the ground. Vending machines line one side of the alley, and shops and signs are on the other. There are no people to be seen, and we certainly don’t see Mike. Immediately after the photo, we read: “If you adjust the brightness and squint hard enough, you can see up his nose.” Benson is obviously looking closely at the photo, and urging the reader—even using the second person voice to do so—to do the same.

A second photo follows, on the same page, of a street in Japan filled with telephone poles, cars, and bicycles. In the distance, there are bodies and a lone bicyclist. Again, however, Mike is not to be seen. It seems clear that Mike’s absence from the photos is meant to underscore Mike’s absence from Benson’s life. Does this mean that the photo the reader sees is the way that Benson sees the photo—the background only and not the foreground—or are we meant to believe that he is simply not sharing the selfies with the reader? Perhaps the selfies are a form of intimate communication between the two men and not something to be shared.

Either way, the photos are an important way that Mike is communicating with Benson, using images as much as words to converse. Benson reflects on this, thinking, “There are plenty of things we should be talking about, but here we are, talking around exactly all of them.” Mike sends a few more photos—on the page opposite the first two images, we see a photo of a small rectangular structure, covered in small drawings. There is Japanese lettering, and the drawings, with stick figures, seem to be done by children. Benson does not describe this photo to the reader, and it’s difficult to understand its significance. It’s possible there’s meant to be a link to Benson’s work as a childcare worker, but it’s hard to know for sure.

In addition to Mike’s absence, these three photos provide us with a sense of where Mike is and what he pays attention to, as well as with a bit of Mike himself. The photos are all included as squares of equal size, so each photo takes up the same amount of space. The photos are in focus and centered; clearly Mike has considered their composition and design. Perhaps most importantly, though, Benson does not really comment on the photos that we are shown. Washington presents the photos as images for us to decipher. They are reminiscent of W.G. Sebald’s work in this way: the photos are offered to the reader without captions, for their interpretation. The result is somewhat disorienting, as we can’t quite tie the photos to the text, and this underscores the disjunction between the two men. They are halfway around the world from each other, and they are not communicating well, or easily.

The fourth and fifth photos appear slightly after the midpoint of the book, when we are in Mike’s point of view. Mike, still in Japan, has recently met someone new, and he’s also had a fight with his father. When he returns to his father’s apartment, he is locked out. We get the feeling, although we don’t know for sure, that there hasn’t been much communication lately between them. Mike starts to text Benson, but then sends him photos instead. He sees text bubbles appear:

They appeared. Disappeared. Appeared. Disappeared. And then they were finally, resolutely, gone, but I waited another five minutes just to be sure.

The bubbles didn’t come back.

So I walked.

Tennoji, on a Saturday night, before the crack of fucking dawn, held an entirely different feel. Save for some stragglers, no one else was on the streets.

On the page, the sentence ends before the word “streets,” and we see two photos. The first is a night photo of a street with neon signs blazing on either side; it is packed with people. The second appears to be of a home, with many plantings and a tree overshadowing the house. Perhaps these are among the photos that Mike sent to which he didn’t receive a response. And perhaps Washington wants these photos to show the difference between what we present to the world in our photos and what we are actually experiencing. Here, again, there is friction between the images that we see and the words on the page. At a time when Mike is in an empty city, alone, we are looking at images of a crowd and of a home. We definitely get the sense that he is missing community, that he is longing for home.

Mike’s father’s illness progresses as the novel moves forward. Mike messages Benson simply to say hello:

I set down the phone, and his response came immediately.

Ben asked me to send him a picture.

It was mid-afternoon. I sent him a photo of the sky.

On the following page, we see, again, an urban perspective, buildings on either side of the frame and wires running down the middle. But this time, we do not see the street. The camera is angled upwards so that we see mostly sky, a large cloud in the center. It’s a black-and-white image, but we imagine that the bright white cloud is in relief against an even brighter blue sky. There is an immediacy to this photo: we assume that Benson asks for the photo and that Mike takes what he is seeing at that moment. The earlier photos that were sent always seemed to be from the past, rather than from the present moment.

There is one line of text on the page following the photo—“He responded immediately, the quickest he’d ever replied:”—and then we see the photo that Benson sends. It is a photo of a small building, with the sign Woods Food Mart hanging above. The clouds in this photo are being lit by a setting sun. Mike realizes:

I recognized the gas station by the apartment. The telephone lines by the Pizza Hut. The way the letters faded on their outer edges.

He’d sent me a photo of his own sky.

This is a beautiful and bittersweet moment of connection. One photo, taken in the moment, is immediately responded to by a similar photo. Benson and Mike are clearly far apart from each other—one photo is of mid-afternoon while the other is of sunset—and so the sky, while similar, is not quite the same. But we can feel the longing for each other in these gestures, in the way that they are both reaching out, trying to connect. Mike says:

After that, for no reason at all, I sent Ben photos of the things around me. The train station. Some old folks on a bench. A sweaty beer at the bar. Some random kids shooting and missing three-pointers by the McDonald’s. It didn’t tell him anything about how I was doing or how I’d been. It wasn’t like there was any information disclosed. But it was a way of speaking, more or less.

This brief moment of communication seems to break through a bit of the distance between them. Benson sends Mike photos, too, including a photo of their front porch and one of their neighbors, although the only photo that we ever see is the one of the gas station.

The final photo is on the last page of the novel. We are back in Benson’s point-of-view, and Mike has returned to Houston. Benson wakes up and looks at his phone. There are messages from a number of people and a handful of photos from Mike, who is lying beside him:

He must have taken them when I wasn’t looking. The first one is of me and his mother. And then there’s another one of just me. And then there’s one of our front porch.

And then there’s one of my butt, filtered and expanded. And then there’s one of Mike, smiling into the camera.

But it’s a real smile. And that’s the one I know I’ll remember. Regardless of how this goes. That’s the one I save.

As at the start of the novel, we don’t get to see Mike in the photo that he sends. We have to imagine that smile. Instead, on the following page, we see a photo of a house with a big front porch, a large tree by its side, obscuring the view. There’s a nice echo here with the photo that Mike sent earlier of the house with the tree in Japan, and we also remember that Benson sent Mike a photo of their porch earlier, when Mike was away. Everything about this photo signals a resolution: a return home, a quietness, a sense of peace. We don’t necessarily know what will happen between Mike and Benson in the future, but this photo provides the same sense of relief that the thought of home often provides.

Washington uses photos in his novel to explore the relationship between the two men, and how though the early photos are difficult to read and understand, images—rather than words—ultimately provide a way for the men to communicate. As readers, we respond to the photos analytically at first—trying to figure out their connection to the text, trying to understand what they tell us about Mike and Benson—but as the novel progresses, we see the later photos in a more visceral way, allowing them to simply express an underlying emotion. That progression creates its own narrative arc. We feel this arc, as it rises and falls, and it works beautifully, beneath and in tandem with the words, echoing the written story of Benson and Mike.