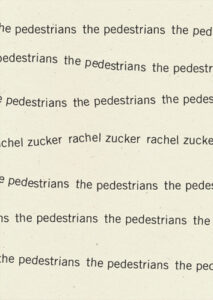

The Pedestrians

The Pedestrians

The Pedestrians

Rachel Zucker

Wave Books, April 2014

160 pages

$18.00

Buy: book

Rachel Zucker is a writer of daunting productivity. The Pedestrians is her sixth poetry collection since 2002; she has also published a memoir, co-authored a book about home birth with Arielle Greenberg, and co-edited two anthologies—this in addition to having three boys of (on the evidence of this volume) moderate-to-high boyishness. Moreover, The Pedestrians could easily be considered two books.

The first seventy-one pages of the book contain five prose pieces collectively titled “Fables.” The pieces are indeed fable-like in the simplicity of their syntax, the plainness of their vocabulary, and their avoidance of proper names; they refrain from pointing morals, though, and their tone reminds one less of the serene La Fontaine than of Joan Didion, with her uncanny compound of white-hot candor and cool control. Read sequentially in one sitting (which I would recommend), they are like mainlining a novel—a novel from which exposition, description, characters’ backstories, and all other novelistic thick description have been refined away, leaving the leanest possible narrative of a marriage passing through a crisis.

If “Fables” is stylistically and thematically about paring things away, eliminating all superfluities, the poems in the following seventy pages (collectively titled “The Pedestrians”) follow the additive principle. Many of its poems use no punctuation but the ampersand, accumulating whole catalogs of proper names in a headlong urban rush of sensory overload. The poem “The Pedestrians”—which, in an appealing irony, seems to document a train ride—can serve as illustration:

[…] the Spanish lovely indecipherable noise

a pleasure not to understand I imagine it’s not all

banal & meaningless like my own daily communication

of course those aren’t synonyms the banal is often full

of meaning a woman coughs all over my air everyone’s

scared to die except the people who aren’t […]

As with the poems of James Schuyler (named a few lines later), sampling a few lines fails to convey the exuberance of these poems, the way their unstoppable chattiness and omnivorous perception can brim over into a feeling of fullness and abundance.

Several poems in the second half of the volume describe dreams, the manifest content of which varies widely, but which always seem to be somehow about being a parent: “I have four or maybe five eggs on the counter. I am preparing / to make something. What if they roll off?”

Encountered separately, “Fables” and “The Pedestrians” might not even strike one as being by the same author; presented together, they demonstrate the extraordinary range of a gifted writer.