The Ploughshares Round-Down: “Die Empty”

If you’re on Twitter, you likely noticed that a new tool took over the twitterverse last week, allowing everyone to identify and re-post their very first tweets. My first? Ahem: I retweeted a friend’s observation that “The writers of the show He-man were frickin’ geniuses”.

I mean, obvs my friend spoke truth. Still, by taking that particular occasion to speak up, I’ll never not have ridden into the Twitterverse on the back of Battle Cat. Dangit.

I’m not the only one laughing at my #firsttweet; collections of “embarrassing first tweets” are making the rounds. (The Independent even noted that Vladamir Putin’s first tweet congratulated Obama on his re-election.) But actually, more than funny, I find my first tweet strangely comforting. It made me realize that, awkward or not, people will only remember our first tweets—or our second, or third—if we never write anything else.

“Don’t Die Full of Your Best Work.”

This is creativity guru Todd Henry’s appeal in his 2013 work, Die Empty. The book’s a surprisingly upbeat repository of advice for getting epic creative work out of your busy life. (Go read it.) But when beginning, it’s hard not to feel a little pummeled by its foundational idea, summed up in a quote from Henry’s friend:

The most valuable land in the world is the graveyard. In the graveyard are buried all of the unwritten novels, never-launched businesses, unreconciled relationships, and all of the other things that people thought, ‘I’ll get around to that tomorrow.’

RIGHT?

No surprise, I couldn’t get Die Empty out of my head this week. I kept thinking, What if all the world would ever know about you is the creative work you’ve completed up to right now? This got unforgivably sentimental, but it reminded me that if my work isn’t what I want it to be, I have to make more. I’m only stuck with what I’ve already done if I don’t make anything else. Writing is the opposite of stasis.

If you feel your work isn’t what it could be, and/or if you’ve lost all sense of creative urgency, here are three right-now stories to get you writing. These people embody the sense of urgency that overtook me this week; they’re adding to their bodies of work while they still can. They demonstrate that it’s possible to overcome definitions and limitations by making more stuff. You can increase your satisfaction with your output by adding to it. Don’t die full of your best work.

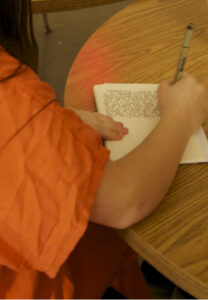

1. Girls in juvenile detention read their poetry to strangers.

I just spent a week writing poetry with the girls in an Ohio juvenile detention center. Some of their lines are still on repeat in my head:

I walk around with a Pretend on my shoulders

I have seen the devil many times in the dark clouds

I am silvertype; black and white

When working in juvenile detention, it’s ridiculously apparent that writing is a version of change. Each student gets to choose where to take her own narrative: what to withhold, what to share, how to name her experience. And while these are beginning poets, they’re great teachers. They can be cynical about a lot of things, but when they write, they believe in it: that it has the power to make them more than their orange suits.

At the end of our week together, they read their poems to a room full of mostly-strangers. Each girl grabbed the mic like she owned it, and I’m still getting emails from guests who can’t get those poems out of their heads. Guests who forgot for a few minutes that they were in a locked-down facility, that the performers were in orange suits.

They defied the label, “incorrigible youth.” You can defy something, too.

2. Edward Snowden appeared at TED 2014. As a robot.

Okay, kind of. What interested me about this was not that Snowden was invited to TED, or that he divided the crowd, or that he titillated viewers with news of more documents that are apparently even more significant than those he’s already released. I was interested in his seeming desire to alter the public story about him: to explain his motivation, his moral dilemma, his hopes for the future. He’s not happy with the content available about him, so the only solution is to keep speaking: adding words and actions to words and actions.

So in an era in which (as he’s noted) everything we do is not only saved and searchable, but possibly surveilled and decontextualized (and potentially construed as damning evidence), Snowden keeps speaking and writing—and then face-timing the TED stage. In spite of the controversy surrounding him, his persistence is motivating. He reminds us that the only hope of altering our stories is to keep writing them.

3. Anita tells a 23-year old story for a new generation.

For those of us too young to have been glued to the news in 1991: Clarence Thomas was only a Supreme Court nominee back then. And that same year, Anita Hill sent a private report to the FBI stating that Thomas had sexually harassed her when he was her supervisor at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Her report was leaked, and Ms. Hill became a public figure when she was forced to testify about her experience to Congress.

Her accusations caused massive political uproar and a media frenzy, and “helped define for the nation what the term ‘sexual harassment’ meant.” Thomas was still appointed to the Supreme Court, but Hill’s ordeal emboldened women all over the country to come forward about their workplace experiences. It also led to the sexual harassment laws with which most of us are now familiar.

Last week, twenty-three years after her now-famous testimony, Anita Hill made the media rounds to publicize a documentary about her experience, entitled, simply, Anita. “We know that in 1991 we started to really understand [sexual harassment] and to take it seriously,” Hill says,

but I think in 2014 we have an opportunity to take it seriously for the young women who are on campuses, and the young women who are in the military. And for the women in workplaces that have not gone addressed.

Anita Hill’s story changed the trajectory of her career and forever impacted the socio-political conversation surrounding gender equality. But it’s inspiring to note that she’s neither content with the work she’s already done, nor deterred by the insults and death threats she’s received. By adding this documentary to the public’s existing story about her, Hill connects with a new generation and emboldens young viewers. “As long as I believe that we can make things better and that this movie can help,” she’s said, “I’m not going to stop.” If Ms. Hill can keep going, I have no excuse.

What—or whose—activities are motivating you to write more?

And what are you doing to make sure you “don’t die with your best work in you”?

Tell us in the comments—we’d love your advice and inspiration.