The Poetic Instant and Creative Criticism

I run a few times a week. Every run is relatively predictable—I know where I’m going, how long it will take me to get there, and how long it will take me to get back—but no matter how often I take a particular route, I’m surprised. I’m surprised to see a unit of soldiers marching down the bike path in their fatigues, carrying weapons. I’m surprised by the guy running in the opposite direction who gives me a high five. I’m surprised by dead raccoon kits in the grass, by deer in the meadow, by turtles, by the bicyclist who almost crashes into me, by the creek’s flooding and by the mud it leaves behind, by enormous herons, by the smell of death, by the smell of magnolia. The route is routine, but there are instants that aren’t—instants of doubt and fatigue, instants of reverie or of speed, instants of surprise that punctuate the familiar landscape because they are embodied, given shape.

This yanking out of our work-a-day expectations and habituations is what French philosopher Gaston Bachelard would call a poetic instant, or the comingling of sudden and surprise. Surprise, what philosopher Edward S. Casey calls the twenty-first-century counterpart to wonder, could be construed as a wishy-washy term relegated to the realm of the hopelessly earnest, the non-quantifiable, the childish, but Casey asks us to consider the destabilizing nature of surprise when it arrives and how it seems to make time palpable. In his essay on Bachelard’s theory of the poetic instant, “The Difference an Instant Makes,” Casey writes:

Only what happens suddenly can truly surprise me; and what surprises me arises suddenly. But the sudden is, strictly speaking, a predicate of time as instantaneous, while the surprising characterizes what arises in time: what “takes us over” (as “sur-prise” signifies in its original meaning), what supervenes in our lives, captivating us…[Surprise] is an arena of poignant intensity: of configurated events. Only something with shape can surprise; but the shape is not that of habitual perception or thought: it is a supervening shape that studs the field of the customary body.

The “field of the customary body” Casey describes could very well be the soccer field I pass on my run, but it could also be a page of text—a field I’ve seen many times. Maybe the field is the act of reading, an endeavor—like running—I’ve engaged in over and over again. And then, suddenly, surprise happens.

I’ve often wondered about the efficacy of my own academic training. What good did it do? How much did I actually learn? I might roll my eyes now at the piles of books I lugged home from the library and the mind-numbing lectures on theory, but the definitive effect hasn’t been (necessarily) a breadth of ready knowledge but rather a facility for surprise and a capacity for shaped responses to texts I call “creative criticism”—a blanket term meant to describe unconventional critical reactions to cultural artifacts. One of the most famous examples of creative criticism is Susan Howe’s 1985 book My Emily Dickinson, the very title a treatise on affinity, connection, and embodiment, and like so many disaffected women writers before me, I found comfort in its ingenuity and in its ecstatic surprise grounded by Howe’s intellectual training. I wondered why it took me so long to read that book after so many years of reading. Oh! I thought, it’s possible to go about this in a completely different way, and by this I mean my innate desire to wrestle with what I’m reading (or watching, or listening to, for that matter). My engagement with texts is routine, but my responses to them are sometimes quite surprising and often visceral, occupying a space where meanings collide and converge in, as Bachelard says, “depth or heights.”

The aim of creative criticism, then, is to revel in surprise, to invite it in as if it were a stranger at your house’s front door—a house being, of course, another of Bachelard’s poignant metaphors for lived experience.

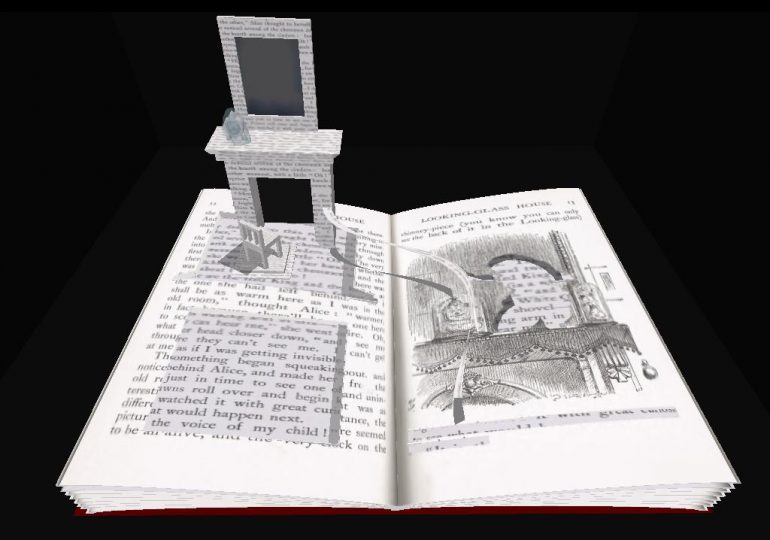

The poet, critic, and artist Jen Town actually made a house in response to poet Karyna McGlynn’s 2017 collection Hothouse, which she published on The Bind, an online journal dedicated to book reviews by and about “women, femme, and non-binary authors.” Of the experience, Town writes:

When I read a book to review, I’m always trying to think of ways to represent the book in a medium other than words. Since Hothouse itself is organized in sections each with the name of a room in the house, the form the review would take was pretty apparent from the get go. I did attempt to build a physical house (out of cardboard) but wasn’t pleased with the quality of my work…I wanted the house to feel like the poems in the book but not be too reductive. Most of the items in the house are there because they are in the book but the rest of the room I had to interpret. What kind of walls and floors would Hothouse have? What should the outside of the house look like? Should the sky be full of stars, maybe a photo of the cosmos? Should it be sunny? Should the house be situated in a forest?

What Town describes is a creative act that required her to stray from the known quantity—the book’s “customary body”—into speculation and surprise after having done the necessary legwork, as it were, to allow for that surprise. Town’s brand of creative criticism literally takes shape (albeit a digital one), as a house, a dwelling the text occupies, but that generalized term could be used to describe critical engagement as etymological exploration, like Dan Beachy-Quick’s A Whaler’s Dictionary, or even mock-biography, like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Yes, Orlando is most often categorized as a work of fiction but concurrent to its novelistic qualities is Woolf’s astute criticism that with wild invention and surprise tackles familiar literary “fields” like Pope and Shakespeare, to name just two examples.

In fact, some of the ripest territory for creative criticism can be found on Shakespeare’s “customary body,” as it is constantly in flux, in conversation with contemporary concerns, interpreted and re-interpreted, given literal shape, personified, and traversed. One might say that theatrical performance is itself an act of creative criticism—a direct embodiment of text that draws profound attention to time, not as simply a unit of measurement, but as subjective experience.

Opportunities for surprise, however, aren’t limited to the stage. Consider Hogarth’s Shakespeare series (to bring the conversation back to Virginia Woolf); established in 2015, the series tapped writers Jeanette Winterson, Margaret Atwood, and many others to novelize and re-contextualize several of Shakespeare’s plays. Could we call the resulting texts creative criticism? I say, why not? Interestingly, the most successful of these ventures, to paraphrase The Millions writer Lauren Marie Scovel, are those that engage with their author’s personal experiences. The creative act, then, is a comingling of text and biography, life and language.

Opportunities for creative engagement with culture abound. “I have a lot of ideas for different media I’d like to use for book reviews,” Town says, “but it’s important that the medium fit the book. I’d love to do an embroidery sample review. I’d like to do a video project review. I’d like to do a giant mural on the side of a building!” The “customary body” Casey describes could very well be our rigid notions about genre and media, barriers writers, artists, and critics like Town intend to dismantle. Surprise can happen, but only if we open the door.