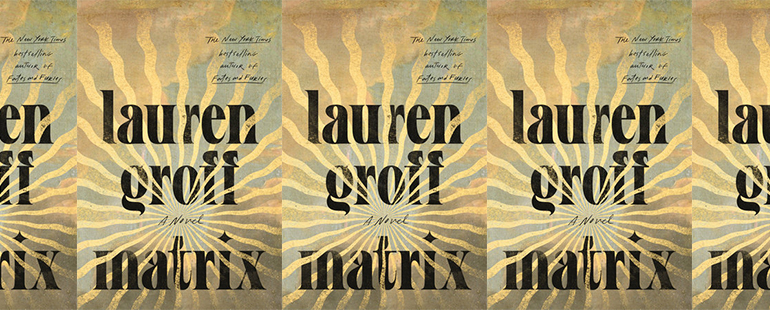

The Power of Women in Matrix

In a world so often ruled by men, there is Eleanor of Aquitaine, who exerts power and influence over France and Angleterre in Lauren Groff’s new novel Matrix, out today, which expands the story of this queen famed for her beauty. Within Eleanor’s world is Marie, “the issue of the Plantagenet violation…[a] bastardess half sister to the crown. By the horrid stain of rape.” Groff’s novel nods to the unidentified poet Marie de France, who may have been Marie, Abbess of Shaftesbury and half-sister to King Henry II of England, Eleanor’s second husband. Groff’s Marie is larger than life—nearly literally—and she writes Breton lais she sends to Eleanor, her greatest love. The first time Marie sees Eleanor, she thinks: “A woman. Powerful as a punch to the chest, the wonder Marie felt then, this first love.” Though this love feels romantic at times, what ultimately rises throughout Matrix is Marie’s admiration for power in the hands of women. First Marie watches her powerful mother, grandmother, and aunts; then forceful Eleanor; and finally Marie herself exercises power while in exile from Eleanor’s court. Despite the novel’s setting in medieval times—the story begins in 1158—Marie’s plight and the calculations Eleanor makes feel similar to how women must take and assert power even now.

Women’s bodies play a critical role in Marie’s story, from her earliest days to her time in exile at a royal abbey. Marie’s mother is blamed for her own rape; her “fault was that she was fetching and a fool, for she didn’t run fast enough.” This victim blaming establishes both that beauty is power and that by being a woman one is always at fault. While Eleanor is famed for her beauty, Marie is constantly denigrated for her looks: “She is tall, a giantess of a maiden, and her elbows and knees stick out, ungainly.” Marie’s body dominates the way she moves through the world. She is constantly reminded that she is “too-huge” and ugly. At Westminster, “Marie appalled everyone with her ravenousness, her rawness, her gauche bigboned body; where most privileges accorded her royal blood she lost due to the faults of her person.” Her body is more unforgivable than her origins since it does not conform to expectations of what a woman’s body should look like. Although Marie is made to feel bad about her body and her lack of beauty in nearly every encounter, she prizes, however, her place in a legacy of powerful, massive women—huntresses, warrioresses, loving women. But because of her body, Eleanor banishes Marie from court, sending her to the abbey, to her “living death,” where she is to serve as prioress and then abbess. Marie recognizes that “she is caught in a great net made by her sex and the excessive height of her body.” Though she loathes the abbey and misses Eleanor’s court, she is stuck. Having seen Eleanor’s forcefulness as a leader, Marie then decides to become powerful herself—to make her life bearable but also to attract the attention and approval of Eleanor.

Even in the abbey, bodies, Marie’s in particular, are surprisingly conspicuous. Upon Marie’s arrival, the magistra “bends to look closely at the girl’s privies, then touches Marie with her cold hands there, saying that this new prioress is so large a person with hands so great and voice so deep and face to unwomanly, it needed to be seen that she is female.” Even within the abbey, Marie physically falls short, her garments fitting too small, the feminine traits expected of nuns appearing to be non-existent in her. And yet she forges on. Before resolving herself to her fate, Marie writes Breton lais and sends them to Eleanor to try to bring about her rescue from the disease-ridden abbey and its starving nuns. The stories in the lais fail to bring about her liberation, so Marie embraces her vocation and begins to learn how to use her body to thrive, resuscitating the floundering abbey and its poor account keeping. Marie cultivates power from within.

At first, she balks at the patriarchal nature of religion. “[W]hy should she, who felt her greatness hot in her blood, be considered lesser because the first woman was molded from a rib and ate a fruit and thus lost lazy Eden?” Marie wonders. “It was senseless.” This tendency to reject religious patriarchal practices builds as Marie’s tenure at the abbey expands, and she firmly establishes that she will never be lesser than a man, just as Eleanor is more formidable than the men in her life. In the early days, “[t]he abbess snores, the horse farts, the day draws on, and Marie’s mind leaps and runs, making her plans.” She is ambitious, recognizing greatness within herself that she wants to capitalize on. She goes on to notice that “[t]here is in fact a change in her, something subtle, but every time she tries to touch it, to turn it around and consider it, she is left holding nothing.” Marie morphs from the bigboned girl enthralled with Eleanor to a leader in her own right and with her own might, slowly but surely establishing the abbey as an island of women. Certainly, she hopes to impress Eleanor with her leadership and with the way in which she turns the abbey from derelict to prosperous, but she simply thrills in her power, too.

Inherent in Marie’s reckoning with her body is her reckoning with her sexuality. While Marie’s love for Eleanor is ambiguous, she has an erotic relationship with her maid, Cecily; this relationship is brought up short by Marie’s exile to the abbey, which begins a long period without sexual intimacy for Marie. She doesn’t have another sexual encounter until the infirmatrix nun at the abbey, Nest, performs oral sex on her, which Nest describes as a release, something medicinal and therefore sanctioned. But Marie is never wholly at ease with her sexuality, especially given her position as a powerful, holy woman. The place where she is aroused is inherently a place of shame for her, and she never dispels her conflation of sexual fulfillment and shame. For example, when she plunges into a river while in the throes of a hot flash, the water cools Marie “at knees at shame at belly so cool at chest and the arms.” It’s a subtle list that reveals that Marie equates the place where she feels pleasure as one of shame, a feeling that always lingers after she feels pleasure.

While Marie smothers her sexuality in part because she perceives it to be unnatural, she often disregards gender roles in the church as being ludicrous and problematic. Though she wasn’t particularly religious before her forced entry into the abbey, Marie comes into religion and seeks ever more important roles in the church. “How strange,” Marie thinks. “Belief has grown upon her. Perhaps, she thinks, it is something like a mold.” She feels so strongly about faith and her role in the nuns’ lives that she eventually wears the vestments and performs Mass and confession herself after the clergy perish in a fire. “There would be no authority but Marie’s authority in this place,” she observes. “And . . . her daughters would be removed, enclosed, safe. They would be self-sufficient, entire unto themselves. An island of women.” Marie becomes ever focused on protecting the nuns and preserving their innocence. She has a vision to build a labyrinth to protect them, which draws attention from the outside world. But “This labyrinth is . . . seen as an act of aggression,” she learns, because “[w]omen act counter to all the laws of submission when they remove themselves from availability.” Just as Eleanor experiences the ire of men for her political decisions, Marie, too, faces hostility for how she runs the abbey. Yet she never lets this hostility daunt her, strengthening her hold over the abbey no matter the costs.

Marie further needles convention in the abbey’s scriptorium, a place generally reserved for men that Marie builds at the abbey to generate more income than the abbey was able to generate through feminine arts like weaving. She reclaims space in the church for her nuns through language. After hearing confession and taking on the nuns’ sadnesses, “Marie likes to go down to the scriptorium and change the verbs and nouns of the missals and psalters into the feminine, for why not when they are meant only to be heard and spoken by women?” she wonders. “She laughs to herself as she does it. Slashing women into the texts feels wicked. It is fun.” Marie revels in claiming space for her sex. She pokes at the absurdity of patriarchal culture and pushes toward the truth that women are more powerful than men because “there is no greater strength than the power in their wombs to create life.” While Marie has never literally born children, she embodies the role of mother to her nuns, and she is fierce with her motherly love. “I am the shepherdess of all the abbey’s souls,” she says, “I am the mother, here to protect and guide all of our sisters and our servants and villeinesses. We are whole ourselves.”

Though she always craves Eleanor’s approval, Marie ultimately spends most of her energy caring for the nuns, serving them. “She would build an invisible abbey made out of her own self, a larger church of her own soul, an edifice of self in which her sisters would grow as babes grow in the dark thrumming heat of the womb,” she thinks, allowing her womb to take on its biological role through her love and care for her sisters. While Marie may have begun as someone so disinterested in the church that she once viewed her assignment to the abbey as a “living death,” she becomes consumed with protecting her charges by creating an island of women made safe from all the ways men harm or oppress women, and marvels at the power she wields, too. She may be perceived as having the massive body of a man, but she defines her gender how she wants, and she protects those who are often exploited—a fate all of them avoid in the end, no matter what goes on beyond the labyrinth.