The Privilege of Interpretation

The history of United States intervention in Central America is long and shameful, and the government has attempted to conceal the death and suffering it has caused in the region. In very different works, the fiction writer Deborah Eisenberg and the poet and essayist Albert Goldbarth use the stories of Americans in Central America to explore questions of how stories are manipulated and who decides which stories are heard.

Eisenberg traveled to Guatemala and Honduras several times in the early 1980s. In an interview with the Telegraph, she says it was “to see where our tax dollars were going.” The narrator of “Holy Week,” one of the stories that came out of these trips, is Dennis, a travel writer visiting an unnamed Central American country whose tourist revenues have “fallen off catastrophically in past decades,” presumably because of political unrest. He’s brought his much younger girlfriend with him. Their guide is McGee, an American who says he used to work for the Department of Agriculture, but as they spend more time with him and his wife, it becomes apparent that he works for the US government in a different capacity—likely the CIA. He makes little effort to disguise this.

Dennis begins the story an oblivious part of the US propaganda machine. His editor was inspired to assign the story when he met McGee in the US. McGee tells him, “it would mean a lot, good press coverage in the States.” Dennis plans to cover the Holy Week festivities, hotels, and especially food. He’s aware of US involvement in the country in the most shallow possible way. He’s read guidebooks, but can’t keep the various countries straight: “All these countries! Veritable stew of armies, guerrilla groups, death squads, wobbly emerging democracies, etc.”

As evidence of death squads, abject poverty, oppressive labor practices, and American responsibility for these problems mount, Dennis’s drafts of his restaurant and hotel reviews become increasingly forced. While he’s writing about tourist restaurants, many people in the country are going hungry (“everything grown for export,” one restaurant owner tells them.) Sarah laughs at Dennis’s flattering description of a restaurant, pointing out that he failed to mention the man with a gun guarding the door. They argue about whether it was a machine gun or a submachine gun, and whether the gun should be included in his piece. Dennis says he can’t include it, because “I’m supposed to be writing about people’s vacations.”

It’s in this scene that Dennis begins to understand and defend his role as a propagandist. He must decide what kind of story he’ll export to the American public in his nationally syndicated column, but there’s never any doubt about which way it will go. We know from Dennis’s own account that it’s the US government, in the form of McGee, who pitched the fluffy travel piece to begin with, so the story Dennis will write is predetermined. Dennis willfully ignores signs of violence that are right in front of him, managing to rationalize soldiers rolling a machine gun down the street on a platform, assuring Sarah, “If there were anything out of the ordinary occurring, someone would tell us.” Dennis’s capacity for self-deception is an important part of his ability to play his part.

Human capacity for self-deception and how it affects the stories we tell is also the connective tissue of “Many Circles,” Goldbarth’s long essay. He’s an unruly and singular essayist, and he ranges widely in “Many Circles.” Two of his many narrative threads are well-researched biographies of 19th century American archaeologists in Central America. Other threads have nothing to do with Central America, but tie in to his greater theme. The essay begins with a traditional hero’s narrative, but Goldbarth warns us right away that it’s not going to stay that way: “If only this were about—and this were only about—respectably credentialed archaeology honcho/pioneer John Lloyd Stephens.”

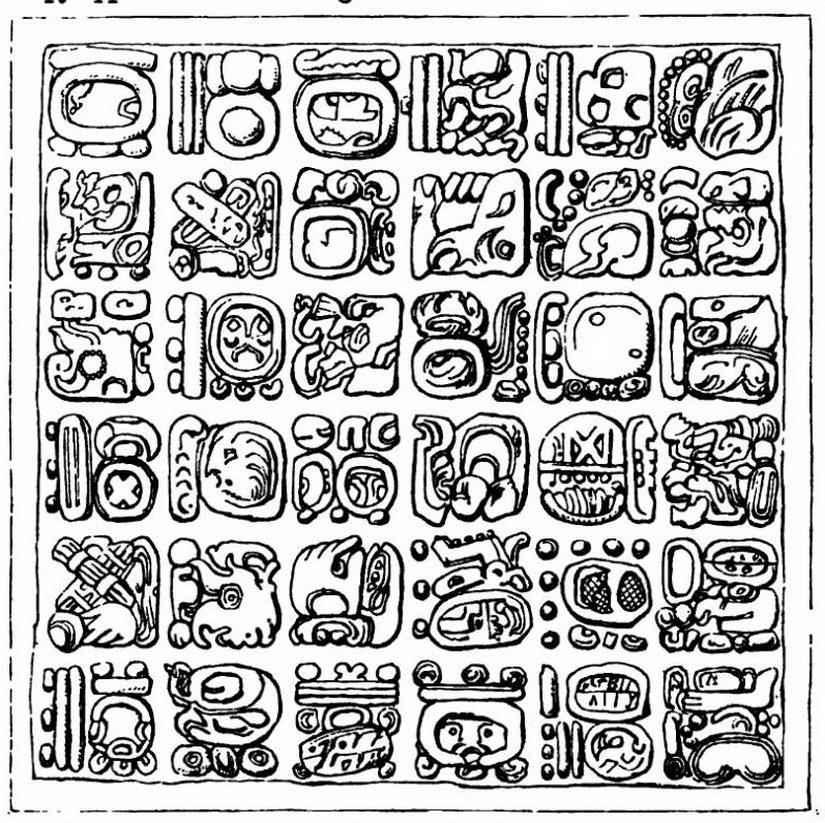

In 1839, Stephens and his draftsman, Frederick Catherwood excavated and documented the Mayan ruins of Copàn, deep in the interior of what was then British Honduras, with the goal of discovering more about Mayan culture. Goldbarth tells the story, drawing from Stephens’ own writings, saying “his hope was […] to conduct ‘an unbiased investigation’ into these ruins.” The eventual result was the publication of several books in the United States, featuring Catherwood’s drawings. In this way, the knowledge they gained in Honduras was exported to the US. Like Dennis, Stephens is in Central America under the auspices of the United States government. In an effort to ease his way as an archaeologist, President Martin Van Buren has appointed him Ambassador to Central America.

Shortly after their arrival in Copàn, they’re faced with the menacing realities of local politics in the form of a violent local leader who’s angry that Stephens has lured away some of his laborers by paying them higher wages to work at the site, upsetting the local economy. They are “daily trading half-blind over political lines of open fire beyond their comprehension.” Goldbarth asks,

And who, in this jumble was the interloper? the son of a son of a son […] who freely said that the ‘idols,’ so far as he was concerned, could stay forever lost? or the Anglo alien, here for such a scant, untenable while, but who had claim to real bonds of affection and knowledge tying him viably to these archaeological wonders?

Goldbarth goes to the heart of colonial rationalization in this passage. If the natives don’t understand what they have and seek to obstruct knowledge and understanding, do the Anglos have a right to it? This line of thinking leads to its logical conclusion. Despite his misgivings and doubts that anyone can own the ruins or the land, Stephens—who remains well regarded for his work as a pioneer in Mayan studies—eventually uses his ambassador’s uniform and other trappings of American imperialism to buy the ancient city from the local leader for a pittance. This colonial logic has much broader implications. During the same era, the US began to justify military intervention throughout the isthmus to establish and protect reliable trade routes in the face of violence caused by local conflicts. Shortly afterwards, American corporations began to exploit the people and the land of Central America to grow bananas for export. The logic Goldbarth describes is the story colonialists were able to tell themselves to justify their escalating efforts to control Central America—and to turn that control to profit.

Goldbarth delves deeper into the notion of self-deception with the history of Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon, a French-American and an Englishwoman who traveled from New York in 1875 to study the same ruins Stephens excavated. They became deeply immersed in their research, learning the language and growing close to the native people. Eager to demonstrate the importance of Mayan civilization, they claimed that the Maya “were the founders of world civilization.” The dates they put forth were insupportable, and the stories they told about the civilization were inventions in the realm of pulp fiction.

Goldbarth writes: “They felt a warranted pride in their exclusive knowledge. It conferred on them a privilege of interpretation.” In the case of the Le Plongeons, their interpretation was absurd and laughable, and they were discredited completely. Eisenberg confronts the reader and Dennis with so much evidence of violence and atrocities in the unnamed country that Dennis’s self-deception quickly becomes absurd, too. On the flight home, he at last admits to himself that he’s seen terrible things.

All right. Yes, the planet is littered with bodies. No one’s going to dispute that—and the bodies are surrounded by clues. But what those clues mean, and where they point—well, that’s something else altogether, isn’t it?

Even as he acknowledges the atrocities, he backpedals, unwilling to end his self-deception by examining American culpability or his own complicity. The question of where the clues point comes back to interpretation. Although Dennis knows where they point and has the material to tell a truer story, his American privilege of interpretation is so powerful that his absurd propagandist story is the one his fellow Americans will have easy access to.

Image: Top of hieroglyphic altar at Copàn (Catherwood, 1840)