Third Spacing-It in Poetry

Thanks to a suggestion from a friend, I’ve been reading a lot of Homi K. Bhabha’s work on Postcolonialism and communicative politics. I’m not really built for critical theory, so I started with Bhabha’s best-known text, The Location of Culture. The fundamental tenet of the book (and this is a very loose interpretation): in a world of colonizers and colonized, our respective positions dictate our communication patterns and dialogues. Just as importantly, the communication patterns of the colonizers and colonized don’t match, so we are unable to directly communicate. Instead, we have to create a separate communicative space outside of colonialism and culture in which to dialogue.

Bhabha’s idea isn’t unique to communication between groups. Individuals within the groups speak different phonetics, complete with conflicting cues and mores, and sometimes, we are unable to directly communicate with the person standing in front of us at the grocery store, let alone a musician in Argentina or a chemist in Utah. Because of this, Bhabha’s idea reminds me of something Miles Davis once said: “If you understood everything I said, you’d be me.”

This is where poetry comes in. No matter how much some poets try to deconstruct or reconstruct, poetry is about communication: conveying ideas, music, and imagery to an audience that may or may not recognize the appropriate poetic cues. By its nature as an artistic construct, poetry is already a third space of communication—not the poet, not the audience, but a part of both. Essentially poetry works in the same way Bhabha describes only without the power dynamics. Or if there are dynamics, they are inverted: the audience has the power because it can always tune out.

In that quote, Miles Davis was talking music theory, but he may as well have been describing what occasionally happens at poetry readings, sometimes the most egregious example of ineffective communication. Scene: the reader steps to the mic, arranges his poems on the lectern, glances wistfully at the audience, then begins to read a poem about why hyphens serve as the leaves of the punctuation tree.

Or maybe the reader arranges his poems, spends some time talking about how the hyphens are autobiographical markers, and they really represent a birthday party said poet had in 1979. The audience might laugh, drink some more wine, and the show goes on with more immediacy.

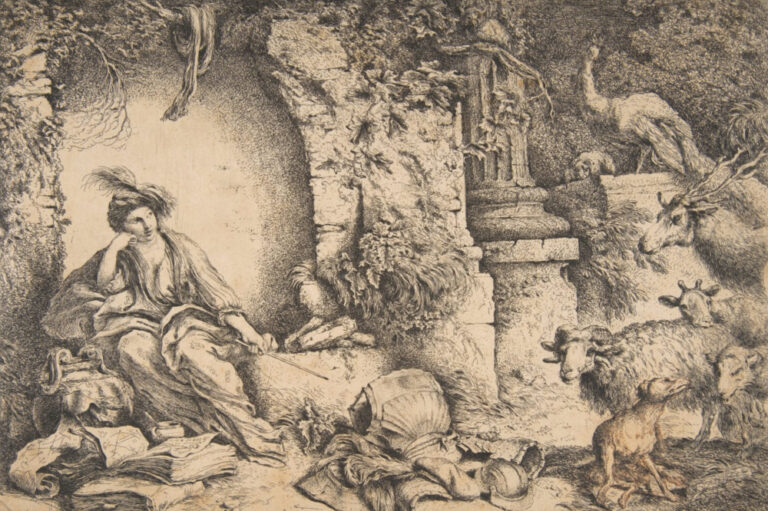

By providing some details about the poem, the poet has created the walls, the window, the door, and the air conditioner for the room of the poem. These trappings help the audience—who in reality is probably not familiar with the nuances of the poet’s work—to understand what is being said. In essence, the details help the reader and audience develop another third space beyond the poem itself for artistic exchange.

I’m not suggesting that banter is always necessary in readings. There are other ways to engage the audience. Sometimes the introduction does the work. Other times, the narrative, music, alliteration, or delivery of the poems fosters third space communication for the audience. But I am suggesting that writers/presenters of poetry should consider the linguistic and intellectual needs of the audience, recognize the communicative letdowns in their poems, and then find a way to invite the audience in.

This is Adrian’s second post for Get Behind the Plough.