This Halloween You Should Be Reading Angela Carter

If you’re looking for some reading to get you in the spirit of Halloween, and your tastes run more to the strange and literary rather than the usual horror fare, you’d be hard pressed to do better than Angela Carter’s short stories. A precursor to writers like Kelly Link, Karen Russell and Katherine Dunn, the imaginative scope of Carter’s work includes jazz and Japan and John Ford and Edgar Allen Poe, inventive language experiments, villains, victims, animals, reimaginings of famous fairy tales with a feminist bent, and a fascination with the life of famed axe murderer Lizzie Borden.

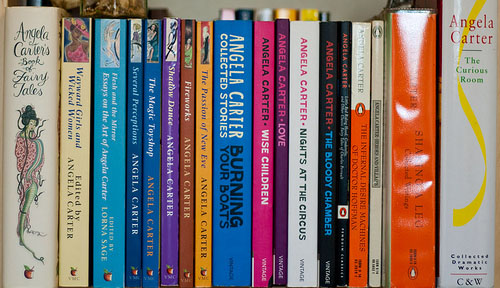

Carter, who was born in 1940 and lived in London, published her first novel in 1966. She continued to write novels and short stories until her death in February of 1992. Her writing is beautifully literary and decidedly British, without being showy or the slightest bit inaccessible to American audiences. As Salman Rushdie says in his introduction to Burning Your Boats, the only complete collection of Carter’s short stories, she “opens an old story for us, like an egg, and finds the new story, the now-story we want to hear, within.” Carter’s short works are strange and original, and well worth seeking out. To prove it, I’ve dug up four of her finest short stories to whet your appetite.

#4: “The Man Who Loved a Double Bass,” from Burning Your Boats.

“All artists, they say, are a little mad,” Carter begins. This is one of her earlier stories, and it focuses on a small-time jazz band doing a circuit of shows, a close-knit group of men at the center of which is Johnny Jameson, the bass player who loves his double bass. A tragic little drama that ends in heart-break, this story is perhaps most interesting because of how it relies heavily on the conventions of fairy tales—every minute readers wait with bated breath for something magical to happen—without actually ever crossing over into the territory of the supernatural. The story is also richly colored by its descriptions of bygone musical subcultures.

#3: “Ashputtle or The Mother’s Ghost,” from American Ghosts and Old World Wonders.

While “The Tiger’s Bride,” Carter’s retelling of “Beauty and The Beast” is perhaps her most well-known retelling of a classic tale, “Ashputtle” reworks the original version of our more contemporary “Cinderella,” and has more nuance and more literary interest. Told in three distinct parts, the story begins with a kind of academic commentary on the story before it’s been told: “[T]he story always begins not with Ashputtle or her stepsisters but with Ashputtle’s mother, as through it is really always the story of her mother even if, at the beginning of the story, the mother herself is just about to exit the narrative because she is at death’s door[.]” And if there is any doubt that this is opinion, the third person point of view cedes midway to first person interjection.

This elaborate framing may seem likely to give away what’s to come, but it doesn’t. Because the story soon moves into the actual narrative and then, when the familiar storyline has been established, this section ends, and a new one begins. Is a mother’s promise never to leave a curse or a blessing? Carter’s version of the classic story downplays the men—father and prince—and the stepsisters, to focus on mother, daughter, and stepmother. And it’s something of a violent ghost story to boot.

#2: “The Company of Wolves,” from The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories.

This frequently anthologized story begins like an entry in a nature guide, but ends in a second person upending of another well-known fairy tale. One of the best features of Carter’s work—what elevates it—is how she structures her stories with imbalances that satisfy as much as they disturb. In Carter’s hands, a story that begins with a pack of wolves can transform midway into a story about a young woman visiting her grandmother in the woods, and even as our expectations are subverted, her story endings always satisfy. “Fear and flee the wolf; for, worst of all, the wolf may be more than he seems,” Carter says, but by the end, this has proven to be simultaneously true and untrue. “The Company of Wolves” is lurid, spooky, and perfect for Halloween.

#1: “The Fall River Axe Murderers,” Black Venus.

“Early in the morning of the fourth of August, 1892, in Fall River, Massachusetts.” This is a story that opens with a sentence fragment, and the rule-breaking continues from there with a long, slow, attentive description of everything but the action that makes Lizzie Borden a compelling character. Instead, Carter details the heat, the heavy clothes of the period, the conditions of the house and the sleeping family, along with occasional spell-breaking asides: “Write him out of the script,” she says of minor characters who won’t appear again.

This slow pace does little to move the story forward—some readers are turned off by it—but for those who are willing to follow Carter to the end, “The Fall River Axe Murderers” is a master work in building slow tension and suspense—and for readers who are surely already informed of how it ends, no less. The story casts Lizzie Borden in a somehow sympathetic light without making her likeable, and it paints the realities of American life in the late 1800’s in unforgettably stinking, sweating, unpleasant detail.

If Carter’s legacy is not in her lush command of language—which it rightfully should be—then surely it is in her ability to break the rules of writing so deftly that readers can’t help but follow with rapt attention, questioning our every assumption about the past and all of the old familiar passed down stories along the way.