Underemployment and George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier

Ten years from the onset of the Great Recession, the American economy has evolved into a complex gig economy, which currently employs a third of the US workforce; an estimated twenty million of those people are in the gig economy—which often comes with low pay and few benefits—because they can’t find stable work elsewhere. Although employment has been on the rise for several years, jobs that are available are often low wage or part time. And people still are losing work altogether: factory worker unemployment has been an issue for decades—especially in the Great Lakes region.

Ten years from the onset of the Great Recession, the American economy has evolved into a complex gig economy, which currently employs a third of the US workforce; an estimated twenty million of those people are in the gig economy—which often comes with low pay and few benefits—because they can’t find stable work elsewhere. Although employment has been on the rise for several years, jobs that are available are often low wage or part time. And people still are losing work altogether: factory worker unemployment has been an issue for decades—especially in the Great Lakes region.

The employment and wage problem does not exist solely in the US, and has occurred in history before. In 1936, George Orwell implanted himself in manufacturing and coal-mining communities in Northern England to explore unemployment and underemployment during the Great Depression. The resulting book, The Road to Wigan Pier, seeks to overturn notions about the working poor. It points out, along the way, many similarities to 2018 America.

Class, one of Orwell’s chief preoccupations, is a very different matter in the United Kingdom compared to the US. The UK class structure has always been much more rigid than ours, and even though it is not as clearly defined as it was in Orwell’s time, that consciousness carries through to today. In the US, there is a tendency to pretend that class doesn’t exist, though many still look down on those who are unemployed and who receive low pay.

Orwell researched his book deeply, living in boarding houses for the working poor and even, at one point, going into a mine. At the time of his research, 1.8 million people were unemployed in the UK—about 13.1 percent of the population—according to the UK Government Statistical Service. Orwell puts the number at two million, and says that when faced with such a number:

It is fatally easy to take this as meaning that two million people are out of work and the rest of the population is fairly comfortable…. This is an enormous under-estimate, because, in the first place, the only people shown on the unemployment figures are those actually drawing the dole –that is, in general, heads of families. ….A Labour Exchange officer told me that to get at the real number of people living on (not drawing) the dole, you have to multiply the official figures by something over three.

We’re not quite at that point in the US. At the peak of the Recession in 2009, unemployment was officially 9.3 percent. According to the US Department of Labor, unemployment is currently down to 4.4 percent. But, as Orwell says, this report is only of those who are “drawing the dole.” US figures include only those who more recently and officially draw on unemployment pay. There are likely millions more than the 14.3 million officially unemployed Americans who are underemployed or have stopped looking for work—or who, as Orwell points out, are working but are not making a living wage.

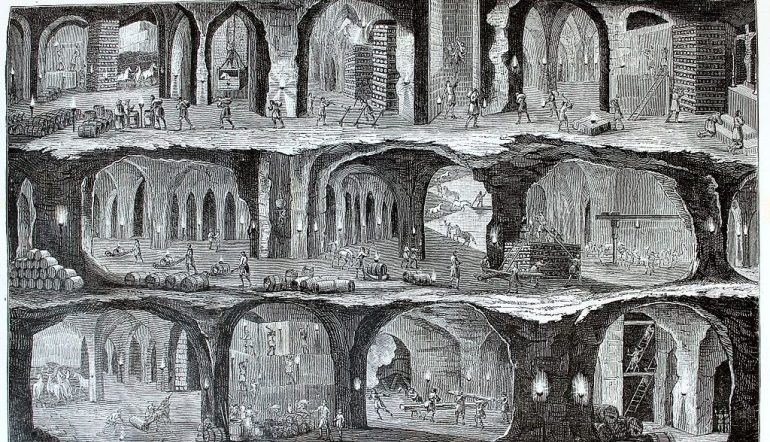

Those people who are portrayed in The Road to Wigan Pier are certainly a testament to the struggle of working but not quite making enough. Most of the living conditions are abysmal—homes are made in buildings that have been condemned but are still drawing rent. What’s worse is the conditions of the coal miners, who are thought of as infinitely dirty by the non-mining world despite, as Orwell points out, being the foundation for everything else: “The machines that keep us alive, and the machines that make the machines, are all directly or indirectly dependent on coal,” Orwell writes. “In the metabolism of the Western world the coal-miner is second in importance only to the man who ploughs the soil.” These miners are not valued despite the backbreaking nature of their work.

Orwell was writing during the heyday of coal, decades before the UK’s mines would be shut down by Margaret Thatcher’s privatization policies of the 1980s. The miners should have been paid more than they received, but what they did was seen as easy and not worthy of pay. Similarly, we live in an era where the foundation of our knowledge-based civilization is our teachers, who are themselves not paid enough.

Walkouts in Oklahoma and West Virginia highlight the plight of underpaid teachers in the United States—a situation in which they are expected to instruct in overcrowded classrooms and with little assistance from local and state governments who continue to decrease their funding. Teachers turn to Kickstarter to replace outdated textbooks and classroom furniture. Kendra Abdel, an elementary school art teacher, spends her own money and “soak[s]… dried-out markers in water to make watercolors, or melt[s]… down broken crayon bits at the end of the year to make new ones” to provide for her students.

We have a tendency to build our countries on the backs of those who we do not value enough to grant a living wage (or any wage). Orwell’s book is a testament to the work of miners and others who are underemployed and unemployed and their dreadful living conditions, but also to these folks as human beings. In the US today, the same situation continues to exist. Orwell’s research, like the reports of so many journalists today, should call us to action.