Welcome to the Literary Jungle

Several times a year I am the recipient of emails or phone calls from friends, colleagues, parents, or complete strangers in search of writing guidance. Often the messages begins, “Hello, my name is Barbra. My daughter wants to be a writer. She’s very talented. Jill Matthews said you might be able to . . .” What follows ranges from, “give some advice” to “edit her trilogy.” These types of messages leave me sighing, not because I don’t enjoy cultivating new voices, but because how those people perceive the writing community and the writing vocation is often vastly different from actuality.

While it would be easy to give advice from my personal experiences, those experiences are just that–personal. I am neither wildly successful nor a complete failure. If anything, I am a literature professor who also writes. This does not make me an expert on writing. It does, however, give me the credentials to discuss writing. In both these casual inquiries and in my Introductory Creative Writing class, I find the most prevalent challenge is trying to guide writers who may have limited or non-existent literary backgrounds. Things like narrative structure, allusions, character development, setting–these fundamentals that we in the writing community take for granted–many beginning writers do not grasp enough to fully employ as writing tools.

The best remedy for this, rather than teaching an entire introduction to narrative course, is to use a selection of readings to facilitate knowledge acquisition which can then be implemented into the person’s writing process. Pairing nonfiction, informative writings with classic pieces of literature can further aid in exposure.

“Shitty First Drafts”

“Shitty First Drafts”

Anne Lamott from Bird by Bird

This hilarious and profanely named essay is the first thing I hand out to my Intro class and on my list of top-recommended works to those seeking writing advice. Lamott shares her personal experiences with the writing process, focusing on the importance that getting something, anything, down on paper is essential. Many new writers assume that there is only one draft and are therefore not receptive to revisions. Or, they become so fixated on writing the perfect thing the first time that they are never able to write anything at all. “Shitty First Drafts” is a fantastic way to share the realities of being a functional writer for novices; even veterans should revisit it from time to time as a reminder of the basics of our process.

Take Away Lesson: Writing is a process.

Quote Worthy: “Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something–anything–down on paper.”

Pair With: “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood. The deconstructed narrative, playing on the idea that there really are no new endings, is easy to grasp and encourages thinking about narrative as a process.

“How to Feed and Keep a Muse”

“How to Feed and Keep a Muse”

Ray Bradbury from Zen and the Art of Writing

Inspiration beyond the trite “write what you know” adage is often hard for writers to come by. Bradbury discusses inspiration through classical references to the Greek idea of a muse, relating it to his own life and work, modeling how a writer may do the same. Beyond abstractions, he gives practical suggestions about drawing inspiration from things like comic strips and television shows, while also subscribing to the much quoted Stephen King theory that a writer must have the time to read in order to have the tools to write. I did have a student tell me once that he found the reading off-putting because Bradbury seems to be “full of himself.” I asked the student (who wanted to write science fiction) if he had read any Bradbury, to which he replied, “No.” After he read the suggested optional reading below, he recanted his statement.

Take Away Lesson: Inspiration can be found anywhere.

Quote Worthy: “When people ask me where I get my ideas, I laugh. How strange–we’re so busy looking out, to find ways and means, we forget to look in.”

Pair With: “The Green Morning” from Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. It showcases how even genre writers may pull from personal truth and understanding.

“The Philosophy of Composition”

“The Philosophy of Composition”

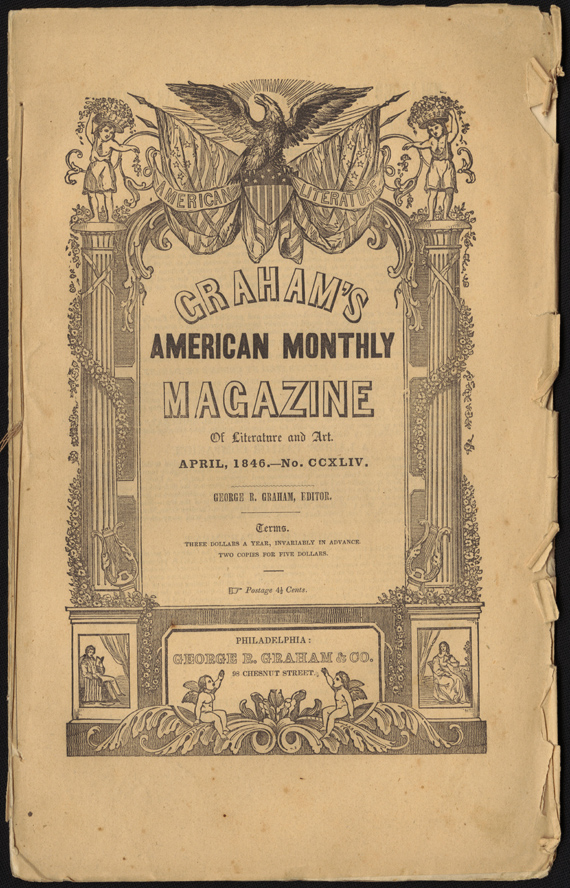

Edgar Allen Poe

Even people familiar with literature have a presupposition that Poe, a grandfather of the American short story, was as mad as his characters. His essay gives a peek into his writing process, showcasing how meticulous and purposeful he was with his work. By deconstructing “The Raven,” Poe illuminates the poetic mind in a masterclass of precision. Although lengthy and sometimes a bit heavy, it is an excellent source for poets, of course–but also writers in general. Poe looks at his poem from both sides–as writer and scholar. His objectivity regarding his own work is admirable. I often revisit this when I feel my process has lost its focus or my work suffering from lack of intention. Some question if the process was actually the one Poe used; even if it isn’t, his willingness to dissect his own work is inspiring.

Take Away Lesson: Writing is a laborious, technical process that should have intention and purpose.

Quote Worthy: “Now I designate Beauty as the province of the poem, merely because it is an obvious rule of Art that effects should be made to spring from direct causes–that objects should be attained through means best adapted for their attainment–no one as yet having been weak enough to deny that peculiar elevation alluded to is most readily attained in a poem. Now the object Truth, or the satisfaction of the intellect, and the object Passion, or the excitement of the heart, are, although attainable to a certain extent in poetry, far more readily attainable in prose.”

Pair With: “The Raven” is an obvious first choice, in part because readers will want to revisit the poem with the newly gained insight. Looking at one of Poe’s prose pieces, such as “The Mask of the Red Death,” with the same insight is even more enlightening.

“Place in Fiction”

“Place in Fiction”

Eudora Welty from The Eye of the Story: Selected Essays and Reviews

A Southern writer in the Faulkner sense, Welty’s lesson on the role of setting in fiction is smart; articulate; and for me reading it as a graduate student, transformative. While specifically geared toward novel writing, it is applicable to any length of fiction and even poetry. So often works I read lack a sense of place. Welty’s discussion is not focused on regional writing, but instead on the role of place in narrative. When utilized appropriately, it can add dimension to fiction that might not otherwise be present. Her examples and suggestions are thought provoking in addition to providing further reading suggestions.

Take Away Lesson: Place is an essential and vital part of fiction.

Quote Worthy: “Place, to the writer at work, is seen in a frame. Not an empty frame, a brimming one. Point of view is a sort of burning-glass, a product of personal experience and time; it is burnished with feelings and sensibilities, charged from moment to moment with the sun-points of imagination.”

Pair With: Any of Welty’s own works would be useful, particularly “A Worn Path.” Those who haven’t read William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” however, should pair the selection with this to see how the place drives the narrative through cunning use of detail.