When We Were Little Women

Like all the books I loved as a kid, Little Women took over my imagination and play and conversation—but in this case, more than any other, the takeover was communal. With my friends, I play-acted scenes from the book. Meg’s stay with the fashionable Moffats. The onset of Beth’s illness. Amy’s humiliation at school over those limes. The dance where Jo meets Laurie. My ratty-haired Barbies often became Jos who dramatically sacrificed their tresses to pay for their mothers’ tickets. When I asked my mom what a poplin was, or a bower, she not only had the answers but remembered the exact episodes of the book the words came from. Nancy McCabe’s recent post on children’s book festivals shows the power these works can hold over their readers, and that was how this book was for us. Bookish friends loved Little Women, non-bookish friends loved Little Women, my older and younger cousins loved Little Women. It was a shared world we could all step into at the same time

I find this widespread appeal a little surprising now. We were all reading Little Women more than a century after it was written, and it isn’t necessarily a book you’d expect to age well. The dialogue can feel mannered:

“Oh, tell me about it! I love dearly to hear people describe their travels.”

“There is a lovely old-fashioned pearl set in the treasure chest, but Mother said real flowers were the prettiest ornament for a young girl…”

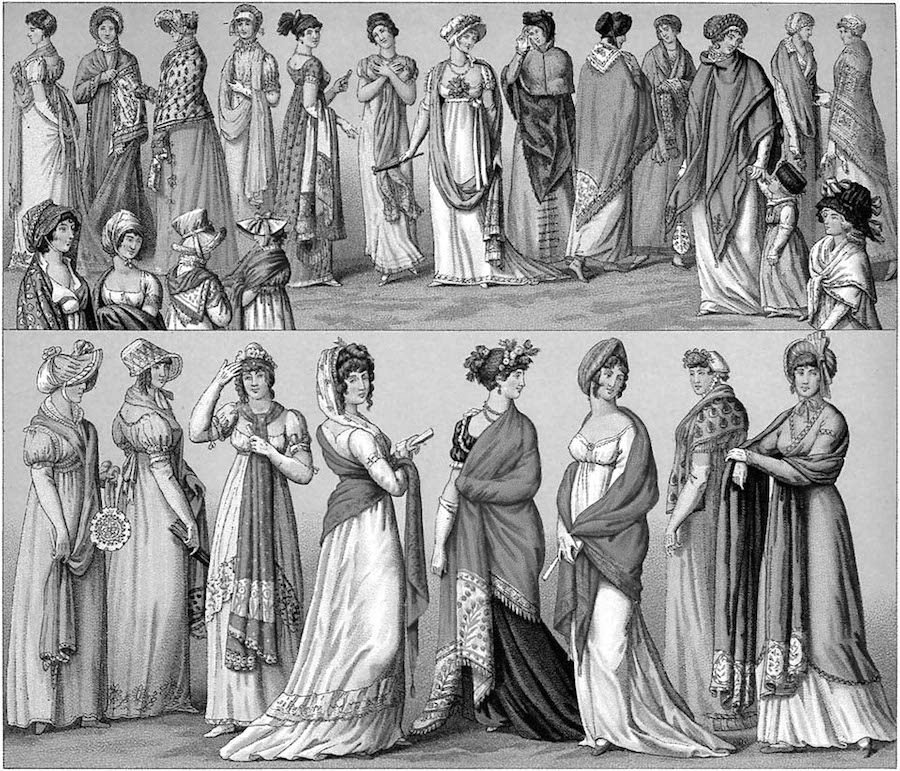

Much of the plot turns on arranging marriages of a very 19th-century kind (husbands who will wisely guide their wives, etc.). And the father figure at the novel’s moral center had a problematic real-life counterpart. Bronson Alcott was a far-sighted Transcendentalist thinker and teacher, as the book suggests, but he also nearly killed his family by making them all subsist on a restricted diet as part of a mismanaged commune (Louisa May Alcott herself mocked the enterprise in a different story, “Transcendental Wild Oats”). The shakiness of Bronson Alcott’s modern reputation might have unsettled the novel’s popularity—and the dated landscape of possibilities available to its female characters might have looked small, still, to readers from a very different time.

The secret to the novel’s endurance in spite of all this, I think, lies in its characters. In the very first scene, we meet the four sisters with whom we’ll spend the whole book, as they sit before the fire. We’re told exactly what each of them is like:

“Margaret, the eldest of the four, was sixteen, and very pretty, being plump and fair, with large eyes, plenty of soft brown hair, a sweet mouth, and white hands, of which she was rather vain.”

“[Jo] had a decided mouth, a comical nose, and sharp, gray eyes, which appeared to see

everything, and were by turns fierce, funny, or thoughtful.”“[Beth’s] father called her ‘Little Miss Tranquility,’ and the name suited her excellently

[…]”“Amy, though the youngest, was a most important person, in her own opinion at least.”

Four sisters, each vivid, but composed, really, of just a few brushstrokes. Here, neatly categorized for us before we’ve made it out of the first chapter, are four different ways of being a girl. There’s something tempting about this drawing of lines. The conversations I had about the book in childhood returned to it again and again: Which one do you think I’m like? You’re like? She’s like?

There was no need to puzzle over the characters themselves. Each of them was known. In every situation, Amy would be graceful but overly concerned with appearances; Jo would be headstrong and brave; Meg would be homey and pretty and sensible; Beth would be gentle and good. We might watch them learn and grow over the course of the book, but still, they held no real mystery. We talked about them because they were useful yardsticks for measuring and trying to understand the much more mysterious girls we all knew in real life—our own selves the most mysterious of all.

The house on which Alcott based the house in Little Women is now a museum in Concord, Massachusetts, called Orchard House. I visited a few years ago. The guided tour slowed down upstairs so we all could linger in the bedrooms that belonged to Louisa (Jo, in the book) and May (Amy). (These are the only two that have been preserved, I forget why.) May’s own pencil drawings sweep across her walls. Louisa’s desk juts from the space between two windows.

Different rooms for different girls.

Of course, none of the real Alcott sisters could have fit into the spaces Little Women carved out for them. No real person could. That’s why those conversations I had in childhood lasted as long as they did: we could reach many conclusions depending on which evidence we chose to inspect. All of us were vain, insecure, brave, shy, kind, cruel, traditional, unorthodox, depending on situation and mood. Real-life girls are messes of contradiction. The characters in a book like Little Women, who can mostly be summed up in phrases, are too simple to be actual models for the young readers who still flock to meet them. But Jo and Meg and Beth and Amy can make those readers ask the kinds of questions about themselves and the people around them that they’ll spend the rest of their lives trying to answer. Because in Little Women those questions are resolvable, its world seems smaller than the real one. Still, it can make a reader look at the real, big world, and widen her eyes.