When Women Writers Become Nightmares

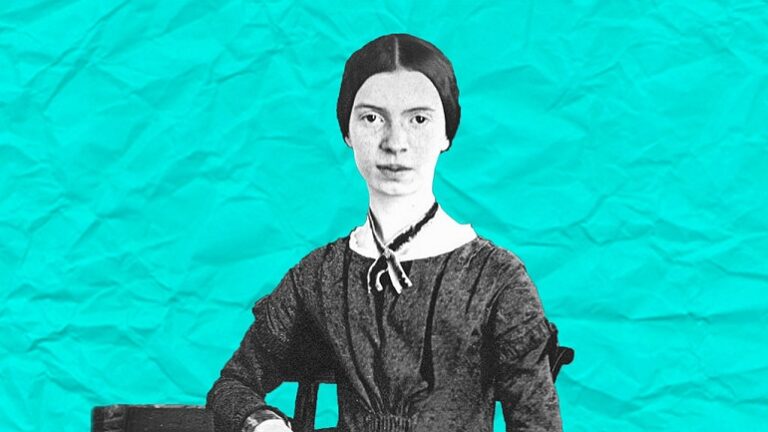

When we go to inspect female-presenting writers, the canon is too familiar: Emily Dickinson, Charlotte Bronte, Jane Austen. There’s no purpose in arguing this. What’s more interesting is uncovering forgotten women writers—women who wrote poetry with T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound in life, or produced movies with Alfred Hitchcock. It was Patricia Highsmith that Hitchcock, an expert on horror, found particularly interesting—knew that her writing would terrify, knew that like the important work of all female writers their writing isn’t forgotten for lack of merit, but tucked under the bed like a monster. A man’s nightmare.

Djuna Barnes

The definition of Barnes’ work as “lesbian” literature is a blunt description of a sharp object, or reductionist. Nightwood, specifically, explores gender fluidity and polyamory—in fact, Robin Vote is bisexual, not a lesbian. Like Barnes, it’s difficult to pin a certain sexual identity to many of the characters in Nightwood, since they’re never verbally declared; Barnes herself never identified her sexuality, simply writing that she “just loved Thelma.” The word “lesbian” is not inherently associated with polyamory (a practice) or trans identity (a gender identity), either, and so shouldn’t corner Barnes’ work only into the lesbian canon of literature. What’s more frustrating is the association of polyamory with non-hetero sexuality, as if alternatives to monogamy and heterosexuality are automatically deviant, other, or “lesbian.” As if “lesbian” is an umbrella term for these things, rain sliding down plastic panels never diluting the definition.

Jean Rhys

Reading Jean Rhys’ biography is like watching smoke curl and disappear into the air. A large portion of the end of her life was spent in recluse while writing Wide Sargasso Sea, her opus. When she finally rose to fame in her own life following the book’s publication, she commented: “It has come too late.” Her statement could describe any number of forgotten works by female-presenting writers. It’s as if, for women writers, forgetting their work is the same as obliterating their personhood.

As the child of a Dominican Creole mother and Welsh father on an English-occupied island, Rhys existed everywhere and nowhere. When she was sent to England at 16 to further her education, teachers begged her father to take her back. She was a hopeless student of the English language, they said, her English as unbodied as her identity.

H.D.

As scholar and writer Kathleen Spivack noted during Mass Poetry this weekend, Hilda Doolittle’s writing has fallen out of fashion. Although she belonged to the infamous avante-garde Imagist group with fellow poet Ezra Pound, her work has faced as much erasure as her sexuality. The same fate was destined for bisexual writer Patricia Highsmith, whose novel The Price of Salt was recently adapted for film as Carol, and whose exclusion from the canon of American writers The Guardian has called “criminal.”

Patricia Highsmith

In looks and opinion, the grit-skinned Patricia Highsmith could be Ayn Rand. Or a character in an Ayn Rand novel. For a woman whose novels were adapted to film and directed by Alfred Hitchcock, it seems unreal that the O’Henry Award winner only gained recognition when Carol premiered this year. She was an alcoholic, anorexic, anemic, suffered from lung cancer and had the persuasion of an oil rig. Absolutely unfeminine and sometimes misogynistic. Perhaps her own rejection of femininity is why the canon of female writers rejected her to begin with.