Why Bother with Craft?

“Craft” was a dirty word at art school, a subtle derogative. The college dropped “and Craft” from their name so recently that the signs on the highway still held those words. Once, in a class critique, a peer called a hand-painted map used to make a stop motion short “crafty,” and my face stung, as if slapped.

Now I deal with another kind of craft; not so much a dirty word but a kind of quiet discussion held among writers and readers. “Craft” is a fluid term; used in aeronautics and astronautics to speak of a single vessel, or the skill of deception, or a verb analogous to “make.” Craft in literature is comprised of narrative elements and literary devices: the nuts and bolts of what makes a story a story.

The first week in an MFA in creative writing, students were told they’d be studying craft and one student objected—said he couldn’t write a craft essay when the choices he made in a narrative were inherent.

They’re not, the professor argued; they’re studied and learned qualities, practiced until they become inherent, or second-nature. Craft in literature is the metaphorical and invisible toolbox you take with you. Like a filmmaker studies the nuances of cameras, microphones, and lighting to create a scene, a writer reads books for syntax, structure, theme, and studies the methods of employing devices like irony and metaphor as a way to point toward meaning, to elucidate a deeper truth. Jack Hart, author of Storycraft, said, “an awareness of all the different forms in which you can tell true stories using narrative techniques is important to succeeding with a broad variety of materials.” (Nieman Storyboard)

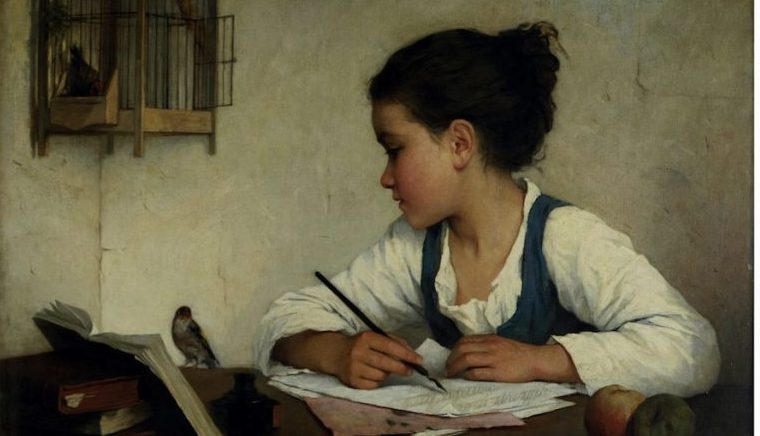

A high school English teacher assigned a semester’s worth of poetry and response papers that addressed the questions, what does it mean? And how does it mean? What is the poem saying, and what is the author using to say it? Alliteration? Allusion? Allegory? The entire class’s individual responses to William Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow” were deemed wrong; it’s not a poem about childhood, loss of innocence, or machines trumping nature, but a poem about a wheelbarrow. Years later, this lesson came back to me in a photography class, as students dissected William Eggleston’s image of a tricycle with similar theories of the loss of innocence. I wanted to scream, maybe it’s just a tricycle!

Effectively teaching and talking about craft is a balance between the mechanics of a piece and the feeling of it, something not so easily categorized. Andrew Simmons, a teacher, is “hesitant to use poems as a mere tool for teaching grammar conventions.” Noting that “the in-class disembowelment of a poem’s meaning can diminish the personal, even transcendent, experience of reading a poem.” Simmons adds, “The point of reading a poem is not to try to ‘solve’ it. Still, that quantifiable process of demystification is precisely what teachers are encouraged to teach students, often in lieu of curating a powerful experience through literature.”

What Simmons touches on sounds less like the shortcomings of poetry or the teachers who assign it, and more a failure of the education system, obsessed with the “quantifiable” and “demystification” of a subject. His reasons for teaching poetry are too numerous to note, but here’s a snippet:

Students can learn how to utilize grammar in their own writing by studying how poets do—and do not—abide by traditional writing rules in their work. Poetry can teach writing and grammar conventions by showing what happens when poets strip them away or pervert them for effect. […] The abuse of conventions helps make the point. In class, it can help a teacher explain the exhausting effect of run-on sentences—or illustrate how clichés weaken an argument. (The Atlantic)

Studying those who “do not abide” or “abuse […] conventions” is sometimes the most edifying. Especially as craft essays are sometimes misconstrued as resulting in formulaic, unimaginative prose. Quotes by the Dalai Lama and Pablo Picasso alike advise to learn the rules so you can break them—that the point of learning them at all is to fracture and transcend conventions. Lidia Yuknavitch, unable to find an adequate word for “experimental” or “innovative” writing:

whatever the word is for taking everything you ever learned about making characters, plots, and storylines and blowing them up […], well, that’s what we do. Whatever the word is for being more in love with words than with conventions and rules about words, that’s us. Lance Olsen and me, we are, and I say this with some authority, language bandits. (Chronology of Water)

Studying craft is not just a love of words but a method in discernment—asking which pieces beg to be deconstructed, which ones are so precious or sacred that they deserve to be left alone, and the acceptance that all interpretations are ultimately subjective.