“Women carry so much of this love and its afterlife”: An Interview with Megan Mayhew Bergman

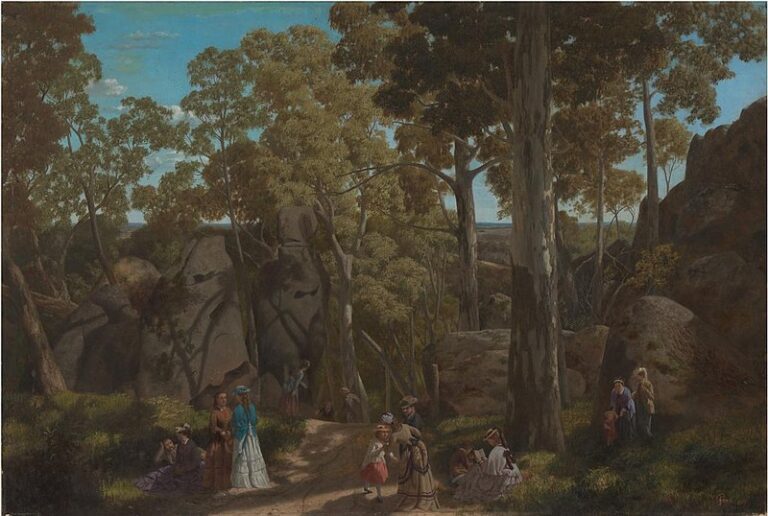

Megan Mayhew Bergman’s third book, How Strange a Season, a collection of stories and a short novel out this week, examines what women create for themselves when pushed past their breaking points. The earth, too, is pushed to its limit in this collection, forced to reckon in its own way with crises it didn’t create. But that’s nothing new for Mayhew Bergman. She’s been writing stories, essays, and articles about climate change and badass women taking care of shit for others with little personal gain for a decade.

In the first story of the collection, “Workhorse,” a woman’s life has revolved around her retired father and “gently estranged husband” for too long. Zach, the husband, is fresh from rehab, where he sought treatment for substance use disorder, and has emptied their bank accounts. She’s kind to him despite her revenge fantasies. She finds escape creating an art installation with exotic endangered flowers, the last she’ll make before giving up her florist shop because she can’t afford to keep it running. Zach—like an annoying gnat— drops by her shop to watch her work three days a week. At the end of the story, readers see what can happen to workhorses, and it isn’t pretty. In “Heirloom,” “Peaches, 1979,” and the collection’s short novel, “Indigo Run,” women must deal with the emotional weight and practical struggles of the problematic land and family history they inherit. More broadly, all the stories deal with the general idea of inheritance—what parts of themselves women bequeath to their children, to one another, to men, and what’s left once those parts are given away. As a woman and reader of these stories, I related to the responsibilities that these women are expected to carry. I recognized in them my own sorrow and rage, humor and heart. And as a writer, who’s learned much from Megan Mayhew Bergman—from reading her stories, from knowing her, and from being taught by her—I gained even more.

I first spoke to Megan six years ago when I’d been accepted to the Bennington Writing Seminars. She was the associate director, and I was weighing my choices of which program to attend. It sounds ridiculous, but Bennington scared me because I’d never been to Vermont. I also had a bad case of imposter syndrome—I was terrified of being alone for ten days surrounded by people way smarter and more talented than me—and the added pressure of new terrain made me want to give it all up. But then I spoke to Megan.

I asked her if it was truly possible for a writer in their late thirties to learn enough through an MFA to publish a book. She told me she hadn’t figured anything out until her thirties. In a touching moment of kismet, I learned that we both remembered where we were when we’d first read Lauren Groff’s “L. DeBard and Aliette” in a 2006 issue of The Atlantic. Megan was so wonderfully supportive in that phone call that I hung up and burst into tears at the thought of not going to Bennington. I was still terrified, but it seemed a necessary terror, like the kind a woman feels nine months pregnant: there was only one way out—I had to go to Bennington.

Have I mentioned that at this point, I had no idea she’d published two lauded story collections? After my crying fit, I googled her and immediately purchased the books, Birds of a Lesser Paradise (2012) and Almost Famous Women (2015). In less than three days, I’d devoured them. Because Megan had also gone to Bennington, they were the first stories I read with the awareness of how deep I’d have to dig, how much I’d have to learn, if I wanted to be a “real” writer.

Reading her new collection, out seven years after her second, I felt right back there—thrilled and floored by the heart and hilarity of it, the emotional depth, each story existing in that magical space that only our best writers inhabit: quietly devastating readers while also making them laugh. In a recent reading with Amy Hempel, who taught Megan at Bennington, they discussed each having taken awhile to write their third books. Booklist called How Strange a Season a “collection perfectly suited for our moment”—and though I’d argue any moment is a good one to read a story by this author, the book is certainly worth the wait.

Amber Wheeler Bacon: You’ve said the first story in How Strange a Season, “Workhorse,” is your favorite in the collection. It is truly the most fun-to-read story I’ve encountered in a long time. It’s hilarious and heartbreaking. It’s the kind of story that feels like it was a delight to write. What made it a favorite? And conversely, what was the story in this collection that gave you the most trouble and why?

Megan Mayhew Bergman: Thank you for noticing my intent—that hilarity and heartbreak are often yoked together for me. I began this story four years ago, and it was written in between the time I gave a talk in the middle of Yosemite and my book tour in Italy, where I spent time in Cagliari. I’m intrigued by dissonance—that churn we all feel between who we aspire to be and who we really are. In “Workhorse” we have people who want to be bold and free—but who also derive meaning from caring for others. I’m also intrigued by the emotional labor of women—so often the emotional glue of families—how we bend, what we carry, the way we try to make it okay for the people we love. In so many of my stories I’m probably asking the same question I ask of myself as a human: How much do we owe each other? Or what if you love a problematic person who isn’t good for you?

Part of “Workhorse” takes place in Italy, which was the place I really found myself in my early twenties in my first long stint away from home. I’ve spent about seven months of my life in Italy and I love what I sense as the Italian commitment to beauty. I found the Sardinian landscape truly seductive, and wanted to set a story there after a long evening at a family dinner where my host made ricotta and gnocchi from scratch, and we sat on the beach at sunset. I also loved being able to explore my favorite intellectual topics of human exceptionalism and atonement.

The story that gave me the most trouble was probably another of my favorites, “A Taste for Lionfish.” I’m always intrigued by the possibility—or impossibility—of redemption, and I wanted to explore that here. A few stories in this book lean into Southern heritage and its complexities, which is, for me, terrifying and necessary terrain. But good intentions can only take you so far, and exploring these topics is a risk—one I needed to take as a human and artist.

AWB: Speaking of workhorses, you once described yourself to me as similar to a Jack Russell Terrier, someone who needed to be busy with lots of work or you’d get yourself into trouble. My first thought of course was, Ooooh, what kind of trouble is Megan getting herself into? But I also wondered then, and still do, how this busyness of yours plays into your writing life. There are many writers who think, If only I could quit my job, then I could really write. But since I’ve known you, you’ve been Associate Director of the Bennington Writing Seminars, a professor at Bennington and Middlebury College, Director of the Robert Frost Stone House Museum, a climate journalist with The Guardian, and director of the Bread Loaf Environmental Conference. I’m pretty sure you also drive for Meals on Wheels. Can you explain how this Jack Russell Terrier soul of yours plays into your writing life?

MMB: Ha. Yes. I am somehow an earnest person who has a particular brand of personal mischief, and I’m beginning to accept this about myself. I’m a restless dreamer. I bore easily. I crave stimulation and connection. I’m sensitive as hell despite experimenting with all types of armor. I have a big appetite. Six years ago, I completed yoga teacher training thinking I could cut some hypothetical red wire inside of myself. I never found it, and I never teach yoga because I can’t tell my left from my right, but the mindfulness skills help. So does therapy.

I hate glorifying busyness; I don’t believe in it. And yet after living with myself for forty-two years, I know I work best if I’m regularly stimulated and able to take risks. I try to find adventures where I can, travel alone a lot, exercise to keep the edge off, and keep my mind busy and growing.

The challenge, and intention for me, is to have a high quality of presence and sincerity wherever I am. So if I’m in the field for a journalism piece, I try to be fully there. If I’m meeting with a student, I try to give them everything I have in that moment. I believe in generosity, and I’ve learned to withhold less, especially love. If I feel it, I often say it, because that’s the world I want to live in.

As for how this plays into my writing life—I think great writing comes from tension and specificity. Having a lot of experiences and getting my hands dirty in the mess of life helps me come to the page feeling like a warm-blooded human with my eyes wide open.

AWB: During one of our conversations, you mentioned that after you had kids, you rewrote all your mothers. I’m wondering if the women characters in How Strange a Season seem different to you from those in your previous collections. To me they seem—bolder? Unafraid of channeling their pain and turning it into rage? Or, at the very least, they’re considering it. After all, the book begins with an Emily Dickenson epigraph—“A wounded Deer—leaps highest”—and ends with the Night Hag who has embraced her rage in a very big way. How do these women characters seem different to you this time around?

MMB: My first collection, Birds of a Lesser Paradise, was largely written in my late twenties as my grad school thesis. I had never lived above the Mason Dixon Line. I was on the cusp of becoming a mother for the first time. My environmental awareness was fresh. I think you can feel that naiveté and unguardedness in the book, especially in terms of the women, and I try to love it for that component, as that’s a big part of who I am.

Almost Famous Women was written in my early thirties, in that moment where I became more aware of the costs of the martyrdom so many women fall into as wives and mothers. I was thinking more about the way women construct full and honest lives. I was angry, and I think I still had a bit of that early adulthood view of “these things happen to us.” Now I’m still angry, but I recognize, after a little more living and therapy, that sometimes the answer is “this is what we do to ourselves. This is the cost of what we allow.” Both are true, but I see the personal accountability angle in a way I didn’t when I was younger.

I’ve said this about every book I’ve ever written, but I believe in post-traumatic enlightenment. I believe in emotional courage and risk, and the expansiveness that comes after realizing you can survive pain.

AWB: You seem to fall in love with imperfect dogs, those with attitudes, “bad” behaviors, and irregular features. All of your dogs, if I’m not mistaken, are rescue dogs. I don’t mean to imply that your main characters, who are all women, need rescuing, but they are similarly quirky. Many of the women in these stories are stuck in lives they don’t want to be living, which causes them to behave badly. Can you talk more about your fascination with these characters (and dogs)?

MMB: I find perfection incredibly boring. I don’t like it in my friends, so I probably don’t like it in my characters either. The older I am, the more space I have in my life for people who have been to the Dark Place and come back from it. I know performance and strategy are both natural elements of being in relationship with one another, but the more I’ve been able to connect deeply with people willing to show me who they really are, the more I am drawn to only that. Sometimes I see people upholding a persona and I think: that’s exhausting. I used to be one, so I know. So I tend to like people and dogs who have been knocked around a bit, who know the value of good love, who are deeply original and learning to move through the world that way.

AWB: You have a climate change column with The Guardian. Much of your fiction and nonfiction grounds itself in the natural world and the damage that humans have done to it. But your writing is so filled with your delight in and love of the natural world, too—the specific joys you take in the feeling of sun on your skin or the way a particular shore bird skims water for its food. This makes your writing on the environment incredibly hopeful. Where is the line for you between hope and dread when it comes to writing about the earth?

MMB: My rational self is pretty cynical and disturbed at this point. I generally don’t believe humans will take responsibility for the pain and suffering they’ve caused the natural world and each other. But—I can’t live that way. I don’t think anyone can. And the natural world is so full of wonder and beauty. There’s plenty to protect and save, and we can slow the suffering and decline, so that’s what we’ve got to lean into at this point. It’s interconnected, and I guess in some earnest way when I’m writing about nature I’m writing in an evangelical capacity. I want to convert you. I want you to see what I see and love what I love.

AWB: Living in the South and loving the South is complicated. I think we’ve talked before about how growing up in Atlanta, which was burned by Sherman’s army during the Civil War, I didn’t realize until high school that Sherman was one of the good guys, and that we were the bad guys. I thought of this reading the short novel, “Indigo Run,” being both drawn to the beauty of coastal South Carolina—where I now live—and, of course, repelled by it too. Here, the Civil War doesn’t feel that far away. One of your main characters, Win, thinks, “The past felt uncomfortably close here, as if it were being kept at bay but ready to rush in at any moment and take root again.” And you’ve got that gorgeous passage when Helena, another main character, lists what no longer exists on the Stillwood estate, the sights and sounds that made it alive, all of which were from the work of slaves. Win, especially, seems to think a lot about the guilt he feels as the descendant of someone who owned a sugar plantation, but he’s not giving up the money that’s come with it. On a craft level, how did you manage this complexity, and was it a conscious choice to not allow these characters the redemption they were hoping for?

MMB: I think you nailed it. I was definitely circling redemption here, and I did not want to grant it. God, we want what is easy. We want to think we deserve better. But if we—and I include myself as someone who has benefited from old systemic issues—aren’t willing to give up our advantages and benefits—do we deserve redemption? Is it even possible, for all the harm we’ve caused collectively?

I was terrified by this book and topic, at a craft level. It’s part of what took so long. There are so many ways to make a misstep when peering into the constructs of whiteness, and there are no guarantees that you achieve what you hope to achieve artistically. And that’s the risk any writer, writing now and beyond, faces, and for good and fair reasons.

AWB: I want to ask you about titles. I’ve always thought you were so good at them. (One of my favorites, “The Two-Thousand Dollar Sock,” appeared in Ploughshares in 2010; Megan also contributed a Ploughshares Solo, “Phoenix,” in 2012.) How Strange a Season is a perfect title for this book, but I can’t find a reference to it in the book. Can you tell us where it came from?

MMB: Thank you. A dear friend had just recommended a book of poems by the Italian poet Patrizia Cavalli:

Onto your sea my ship set sail,

(dentro il tuo mare viaggiava la mia nave)

Into that sea I sank and was born.

(Dentro quell mare mi sono immersa e nacqui)

I am struck by how strange a season it is

And by how my body felt the cold.

How Strange a Season is a perfect title for me, privately, because it speaks to the weirdness at the end of the world—that it can somehow be both profound and banal, unprecedented, unfolding, remarkable.

AWB: Also, I’m curious about your choice in titling the novel “Indigo Run.” You could have called it “Stillwood,” the name of the crumbling manor which used to be a thriving plantation before the Civil War, but instead you named it after the place on the property where the servants and farmhands live. There’s both “suffering and joy” here, whereas there seems to be only suffering at Stillwood. Skip and Win are drawn to Indigo Run because of Marie and Ase. I’m sure they’d much rather be there with them than sweating underneath Marlon Glass’s portrait hanging in the Stillwood house. And I keep going back to this line that the servant Jane tells Skip when Skip asks for a story about the Indigo Runners—Jane replies, “People like your family start taking too much, and the Indigo Runners take it back.” But of course, Skip’s family has been taking too much since purchasing the plantation in 1754. All of this is to say that I can feel in my bones why “Indigo Run” is the title, but I can’t put it into coherent words. Do you have the words, or did you just know it was the title?

MMB: I like the concept of stealing—who is actually stealing from whom? A piece of this novel is about labor and profit. Another piece is about what we still celebrate in the south. People still get married at plantations, and there is a multi-million dollar tourism industry built around them. Why do we still find these places beautiful? Why do we glorify them? I like that Indigo Run—the terrain of the servants—has this deep flash of bluish-purple, something beautiful and haunted, something on the move, some countercurrent and vivacity.

AWB: Continuing with the novel—and redemption—two women in the beginning pretend to see visions of the Virgin Mary, and at the end, you’ve got a revival where your main character, Skip, is unable to retrieve a Jesus statue from the sandy bottom of a river. She’s only a child—and she’s tried so hard!—but can’t redeem her family or their home. Was writing about religion unavoidable because you were writing about South Carolina during the 1920s and ’30s? I’d love to know how and when the religious imagery started showing up in the writing process.

MMB: I tried so hard—so hard—to be a spiritual person in my youth. I’m wired for it. I love mysticism and morality. I love trying to do the right thing. I love singing with a room full of people. But when I was in sixth grade, I knew I wasn’t capable of being a Believer, and when I expressed that to friends and family as a young person in South Carolina, I was met with a lot of judgement, which converted itself into shame for a while. As I got older, I realized that being “religious” cannot be equated with being moral, and that all endeavors in those directions are slippery and subjective. As a person raised in the church, I was indoctrinated. It’s probably why I’m a short story writer; sermons have that perfect arc and attention to sound. But what I brought into this novel, as much as I could, is that one, there is often a desperate personal pursuit to feel worthy and good; two, we’re all susceptible to magical thinking; and three, professing oneself as belonging to a particular brand of religion does not actually lay down a path of redemption. I’ll never believe that as long as I live. There’s no easy absolution, no insurance policy. It’s the human work, and even then I don’t think there’s a finish line.

AWB: I saw you read from an early version of “The Night Hag” in June of 2017 in Vermont. I’m not sure you remember, but during that reading, your voice broke while reading a particular section. I remember walking out of Deane Carriage Barn and hoping that I’d someday come to feel for my characters so much that they made me cry. And though it can be sad, there are hilarious moments in this story too. I laughed audibly when the Night Hag gives a “pageant-worthy smile” after filing her teeth into points. What is it about the Night Hag that so moves you? What about her fascinates you?

MMB: I remember that moment too. And I think crying at your own story is worse than laughing at your own joke, but in that moment, behind the podium, I knew the connective tissue between my own personal experience and what I’d written. Love makes us royally stupid and sacrificial. I guess I was ultimately thinking a lot about the transmutation of pain—what it becomes over time. Sometimes righteous anger. Sometimes passion. Sometimes madness. I was thinking about what it feels like to lose your idealism about romantic love. What comes after conventional beauty or the loosening of the domestic unit. And the electricity and spare energy of it all. I am one of those people who loves love and feels it ferociously despite knowing all about biochemistry and attachment theory, a cynical dreamer—but damn it, doesn’t love send us in the strangest, most ill-advised directions, fueling our decision-making and fantasy lives for years? And in my observations, women carry so much of this love and its afterlife. There’s a lot to be angry about. There always has been. And yet I think women do such beautiful things with their pain.

AWB: Who have you been reading lately? And of course I can’t let you go without annoying you about when your next book, a nonfiction project on the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, is due out.

MMB: I’m reading for teaching—I’m focused on women and conservation right now (Rachel Carson, Camille Dungy), and a class on word and image, which is a personal favorite ([Susan] Sontag, Leanne Shapton, Sally Mann, Gordon Parks, Teju Cole).

My draft of the Sweethearts book is due this summer. I’m deep in archival research, which I actually love. If you have old boxes of memorabilia, I want to look through them. I love other people’s boxes of memorabilia. I think of myself as being of service to the story. I hope I can largely disappear and let the band come forward. I can’t wait to share the new research with readers.