Writers: Go and Sin Some More.

By the time you read this, I’ll be in London, having just given a paper on my (very erotic) manipulations of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poetry. (More on that in a minute.)

By the time you read this, I’ll be in London, having just given a paper on my (very erotic) manipulations of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poetry. (More on that in a minute.)

Meanwhile, in my songwriter life, I’m preparing to record some songs that leap beyond the safe bounds of my previous work.

Both projects have me living in what I once considered Writing Sin: using found texts, telling family secrets, singing the blues. I’ve mined my own Aversions, which is threatening my sense of artistic identity. I’m waiting for some writing god to send a lightning bolt. It’s invigorating—and terrifying.

Which is why, as this London trip looms, I’ve been collecting photos of people giving the camera the finger. It’s also why I’ve found myself dwelling on the kick-in-the-ass wisdom of musician/artist Brian Eno.

As artists, the feeling of terror is a sign to keep going. But sometimes, at the edge of what we’ve called “Artistic Sin,” we need a good shove. So, in the name of burning down our precious Safe Zones, here’s a call to Go and sin some more.

1. Let There Be Sin.

What if you were to begin at the very place you’re afraid to end up? If you get it out of the way, what happens? Name your cardinal writing sins. Commit them. Give yourself the chance to see there’s no hell.

What do you think is too secret, too shameful, too boring to write?

What do you think is too secret, too shameful, too boring to write?

Or perhaps: what kind of writing earns your disapproval or disdain? What do you regularly censor, avoid, edit out?

If you can complete the sentence, “I would never write (about) ____,”

or even, “I would never want someone to say that my work was____,” start precisely with those blanks.

Of course there’s no inherent value in writing something that’s culturally taboo, personally revealing, or simply bad craftsmanship, and what you’ve personally labeled “Writing Sin” may be none of these.

But committing your “sins” will make you acknowledge the world you’ve kept at bay, getting you immediately past your own limits. “When people censor themselves,” Brian Eno has said, “they’re just as likely to get rid of the good bits as the bad bits.” When you protect your boundaries as a writer, you may be hoarding your best work.

So maybe you hate sentimental poetry. Or maybe you’ve told yourself you’ll never write a political poem. Okay. Go write one. The result may not actually be a sentimental or political poem at all. But it will certainly be different than the pious thing you’d have written in your safe zone.

(Note: telling yourself your political poem won’t actually end up as a political poem is cheating. Forget that part. The sin has to be real.)

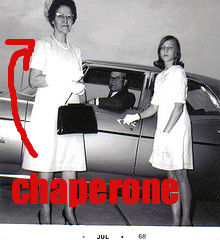

2. Get Rid of Your Chaperones.

Sometimes your literary prejudices prevent you from starting something. But sometimes the problem comes later: you’ve got habits, opinions, and ready judgments that act as Chaperones. They keep an eye on your every writing move, keeping you from anything shady (read: awesome).

Sometimes your literary prejudices prevent you from starting something. But sometimes the problem comes later: you’ve got habits, opinions, and ready judgments that act as Chaperones. They keep an eye on your every writing move, keeping you from anything shady (read: awesome).

But you won’t get anywhere until you set off on your own. Your guardians keep you “safe,” but they also keep you boring. You have to chase your creative interests, even when they cross your lines—or reek of your own disdain.

Think about your practice, your process, your habits. Are you generally reading the same things? Loving, hating, avoiding the same things? What have you dismissed out of hand? Forget them. You can do your gatekeeping after your work is written. Until then, surround yourself with temptation. Make a ruckus. Tear the place apart. (Need some inspiration? Check this out.)

3. Do It “Wrong.”

If you try writing the stuff you’ve been avoiding, you’ll probably feel like you’re “doing it wrong.” You’re new to the genre, phrasing, form, experience, so you lack the sense of judgment that usually has you slamming your gavel left and right.

If you try writing the stuff you’ve been avoiding, you’ll probably feel like you’re “doing it wrong.” You’re new to the genre, phrasing, form, experience, so you lack the sense of judgment that usually has you slamming your gavel left and right.

To that I say —GOOD! Live without the judge for once. If you think you’re doing it wrong, fabulous. Do it wrong. “[T]he mistakes always become interesting,” says Eno. Example?

“The distorted guitar sound is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.”

Such “mistakes” can only happen in a new place. And they just might make great art.

4. Steal Sin. And Words.

Austin Kleon became a bestselling author by urging us to “steal like artists.” But he failed to mention that “stealing” can help us access not only the kind of work we admire, but the kind we’ve kept off-limits.

If you can’t get yourself to move into the topics, forms, styles, or secrets you find fearsome or unworthy, well—stop being a wuss. But also, who—or what—is already there? And how might you “collaborate” with this author or work?

For instance, manipulating Hopkins’ texts provided language, syntax, rhythm, tone—points of departure for a genre I hadn’t tried. I’d never considered writing erotica, but I began this project to give voice both to Hopkins’ repressed desires, and to his conflation of sexuality and religious devotion. Trusting his words got me past my prudish editor:

For instance, manipulating Hopkins’ texts provided language, syntax, rhythm, tone—points of departure for a genre I hadn’t tried. I’d never considered writing erotica, but I began this project to give voice both to Hopkins’ repressed desires, and to his conflation of sexuality and religious devotion. Trusting his words got me past my prudish editor:

I am soft

mined with a motion, a drift

And it crowds

O Christ, Christ, come quickly

My job was to redact, recontextualize, read into. It’s a lot of work, but it’s a different kind of work—another kind of writing. It gave me a beginning.

So: find writers who already do what you’ve kept off-limits. Who’s living in the “sin” you can’t get yourself to commit? Mine her words, tone, rhythms, forms, and topics for your own purposes.

In other words, get other words.

(But um, don’t plagiarize.)

5. Play to Your Own Interest

(aka Give Yourself a Reaction)

To have any sense of play, you have to lower the stakes. If we don’t make a practice of writing “for fun,” we’re cheating ourselves and our crafts.

To have any sense of play, you have to lower the stakes. If we don’t make a practice of writing “for fun,” we’re cheating ourselves and our crafts.

My music has generally lived in a folkish singer/songwriter world. And in that world, I can’t write a song about “douchebags.” No one would appreciate it, even as social commentary. It’d be radio unfriendly, and my fans would be distracted by the use of an “inappropriate” word over and over again. I’d probably get nasty letters. (These are things I tell myself when falling asleep at night.)

But what if I wrote the song anyway? Just to get the idea out, for fun?

One day a friend told me about some particularly horrifying douchebaggery. I was incensed, and when I got home, I sat down with a piano hook that’d been taunting me for weeks. What I ended up singing was,

Oh boy, can you be bad?

Can you be “buy a few drinks for me, hope I don’t think for me” bad?

Oh boy, can you be bad?

Can you be “hover above me and tell me you love me” bad?Cause I’ve got it bad for the douchebags…

It developed a saucy hook for its tongue-in-cheek punch in a dbag’s face, and it’s great fun to perform. It ridiculous. It’s not my genre (whatever that is). And/but it turned out to be a crowd favorite. People got it.

Lesson learned. Because while working on that song, everything I wrote made me recoil. But for some reason, that day I just went with it: I tried to recreate that feeling of recoil again and again. I was laughing out loud. Since I could win a lot of Taking-Myself-Too-Seriously contests, this kind of play was new to me – and it became a profound lesson. If I’d decided never to perform the song for anyone, I had at least interested myself. And I gave the finger to my own NO—a feat for any of us.

So let yourself play. Find out what that means for you. See where your low stakes can take you. One more from Mr. Eno:

“You work on a piece of music, you put in certain ingredients, and suddenly they react in a way you hadn’t predicted. If you’re alert to that reaction, that’s what you work from. If you’re stupid, you try to cancel that reaction out.

“A lot of people have such a fixed image of what the product should be that they refuse to allow any deviation. Again and again, they’ll force the music into a mold until it goes where they want it to go. This generally leads to quite uninteresting music – or uninteresting anything.”

So here’s to deviation, to sin, and to letting the creeps in. Go terrify yourself.

- How are you pushing past your edges?

- How do you approach new or “dangerous” territory as a writer?

- How do you develop courage to write it, and to share it?