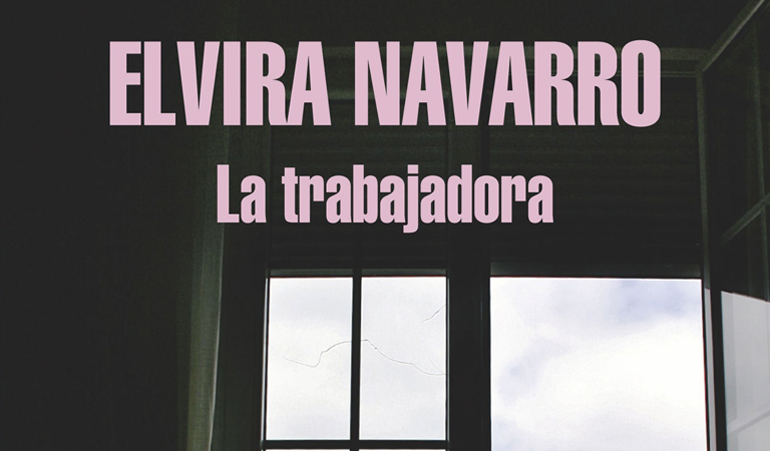

You Can’t Trust Anybody in Elvira Navarro’s A Working Woman (And What That Says About Us)

I’m increasingly fascinated with characters who buy out of the system, both in literature and life. I wrote my first book about this very thing as it relates to the Mexican drug war. Elvira Navarro’s A Working Woman (Two Lines Press) touches on this as it relates to the Spanish economic crisis. But I also talk about the very real characters, too, with my childhood best friend who isn’t a writer but a DC insider who seems just as confounded by the mechanizations of his city these days as everyone else.

We talk about our old things—the Spurs, personal/professional life, marriage, music, books—but lately we’ve been talking about the news a lot like (I imagine) everyone else. It used to be that you could forecast certain things: elections, poll numbers, pledged money, persuadable voters, approval ratings, etc. My best friend made his career on big data. But what should you do when people buy out of an old system en masse? When people cleave off and cleave out an alternative truth and reality for themselves?

In reaction to the current anti-realpolitik, I can’t help but wonder if I’ve done the same but to the other extreme. To root yourself in reality in 2017 is, to some extent, to rage against the post-truth era. The truth is now radical, which is weird! I like to think of myself as rational and self-admittedly not very edgy. Of course, I believe I’m in-the-right: I’m a staunch feminist. I believe in social justice. Being a professor, I believe in empirical and peer-reviewed research and the truth. In sum I believe in, you know, not being a bad person. And only recently, in the wake of certain conversations with my childhood best friend, I’ve come to wonder: is that because I can still afford to buy into that system? Because, in some sense (however small the gains might seem to me), to the people who bought out of the system, might I be a perceived winner of the old status quo? Is it that I can still afford to be not a bad person? Moreover, would I feel the same had the system failed me?

I’d like to think, yeah, I’d still be into not being a bad person. Though in heeding the realities of 2017 I can’t not look away from those characters who opted out of that seemingly rational decision—rooted in human decency—not to be bigoted, not to be racist, not to be misogynist. In a sense, those who opted out of being a decent human being. But then what is that anymore? And is that definition centered?

Elvira Navarro’s A Working Woman, translated by Christina MacSweeney, interrogates the psyche of characters mired by the Spanish economic crisis and the realities and lies they build around themselves in search of catharsis.

The novel is narrated by dual unreliable protagonists, Elisa and Susana, who become roommates at the urging of Elisa’s friend, German, who plays a key role in the disintegration of their relationship toward the end of the book.

The novel opens with Elisa’s disclaimer that “this story is based on what Susana told me about her madness. I’ve added some of my own reactions, but to be honest, they are very few . . . ,” which keys us into Elisa’s own penchant for reality distortion, for rewriting the events as they actually happened. Perhaps, as a form of escapism and/or longing for the literary novel Elisa wants to write or perhaps as a way to take Susana down a peg if only in her own mind.

By the end of the book we’re not so sure if Elisa has crafted this narrative from her own reality as a struggling copyeditor at a large (but uninspiring) Spanish literary press, or if all of it (her entire subjectivity as presented to us) is just another alternative reality that’s actually part of her novel-in-progress, which we know she’s writing—a simulacrum of her true life, a coping mechanism alternative reality which she uses to deal with her personal traumas of finding herself further and further outside of the geographic valence of her old pricey apartment at the heart of Madrid, which is to say further and further outside of high-brow society and definitely further outside of economic security amidst a shrinking book market that rarely pays Elisa what she’s owed on time.

From Elisa’s opening lines, we jump into first person Susana who, presumably using Elisa as a therapist or sounding board, opens up (but not really because she’s unreliable) about her frustrated sexual desires and her relationship with Fabio, a man who has dwarfism, who fulfills them. It becomes apparent as the book progresses and Elisa’s voice begins to dominate the narrative that we realize Susana is a pathological liar unwilling or incapable of any true intimacy, which frustrates Elisa who wants to know the truth about this woman she’s living with.

We come to learn, via Elisa, that Susana lives in a curated present informed by an imagined past. It’s no surprise this tendency toward curation is what ultimately leads Susana to an almost accidental career in visual art toward the end of the book. Susana’s success in part widens the rift between the roommates, though the full realization of this decayed interpersonal fabric is foreshadowed in Elisa’s sense of dread that’s reflected throughout her sections of the book.

Elisa finds herself fascinated with the decay of the neighborhood around her which is located in the outskirts of Madrid, a place where historically and presently the undesirables of the city have been pushed out to live. Nearby are the ruins of a former prison Elisa keeps returning to. And the neighborhood itself becomes a kind of tether back to reality and a reminder to Elisa about the unsustainability and inescapability of her life that’s constantly under assault from the financial demands of life, which are actually very modest.

For both characters, to disengage from reality is to survive. To confront reality is to exacerbate their psychoses. I think deep down, as they’re living it in the moment, both Susana and Elisa know this disengagement from reality and each other is irrational but necessary. And the tragedy when they finally do bridge the gap between them—when they have to cooperate within the parameters of a mutual reality—is that their fears are not only confirmed but realized when everything comes unraveled. Reality undoes them. And nothing is ever the same again.

Bringing this full circle, I think what fascinates me about this book is that I’d never thought about post-truth as a coping mechanism before. It brings up the question: how much of our dignity is tied to the way we interface with reality? And what becomes of us when reality does not validate who we tell ourselves we really are? Or who we should be?

Navarro’s book was originally published in Spanish in 2014, long before the 2016 presidential election. So, it’s not as if the idea of post-truth and reality warping in A Working Woman are in conversation—they’re not. But I also think there are parallels that can be drawn between the populist moment we’re in today and, say, the things that have given rise to populism across Europe in the wake of the financial crises there, especially the Spanish economic crisis.

Reading through A Working Woman, Elisa and Susana are characters whose chaos definitely affects the way they operate in the world, but they have tendencies to implode into themselves rather than explode. I am haunted by these characters, especially when I think of the very legitimate leftist populist gripes concerning the capitalist exploitation of cheap labor (Elisa) or the isolation and desire for human connection experienced by workers heavily involved in the gig economy (Susana). But what is the left’s relationship to post-truth? I think we have one, though it looks something more like that implosion than explosion.

We now know that economic insecurity has played no small part in the shift into post-truth. And part of what I wonder now is how much of my own anxiety about the current era comes from the fact that so many people have bought out of the system in which I, like I suspect many readers here, were winners (if only perceived winners) of that system. Readers, literati, mostly college-educated, employed, probably middle-ish class. Does that make us losers in the post-truth era? The reality of that has yet to unravel.