Zadie Smith’s Exploration of Experience as Authority

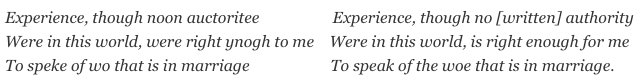

In the introduction to her acclaimed 2021 play, The Wife of Willesden, Zadie Smith explains what drew her to transform a medieval text, Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th-century The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale, into a contemporary play: “from the moment Alyson opens her mouth—Experience, though noon auctoritee / Were in this world, were right ynogh to me / To speke of wo that is in marriage—I knew that she was speaking to me, and that she was a Kilburn girl at heart. For Alyson’s voice—brash, honest, cheeky, salacious, outrageous, unapologetic—is one I’ve heard and loved all my life: in the flats, at school, in the playgrounds of my childhood and then the pubs of my maturity, at bus stops, in shops, and of course up and down the Kilburn High Road, any day of the week. The words may be different but the spirit is the same.”

As Smith herself points out, this feels a shocking thing to claim. Chaucer wrote The Wife of Bath more than six hundred years ago as part of The Canterbury Tales, a complex, unfinished text composed of different stories told by a group of people from all walks of medieval life, amusing themselves while on a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket. And while The Wife of Bath is perhaps the most famous of all The Canterbury Tales—in no small part because the teller of the tale, Alyson, the Wife of Bath, is quite the character—it’s a poem that is grounded in a very particular context: late medieval debates over sex and authority (the navigation of which is so complex that historians of sexuality constructed a flowchart). This is, as Smith puts it, a sexual politics “that would seem as distant as the moon.”

And yet, Smith knows that Alyson was speaking to her, a fact Smith finds grounded in these opening lines of The Wife of Bath:

In her medieval context, the Wife of Bath’s lines are boldly contentious: they insist on the authority of her own experience as a woman, as a wife, over and against that of written authorities, synonymous here with clerical authority. What follows in the rest of what is commonly called The Wife of Bath’s Prologue is a detailed, often comedic, almost always scandalous, account of exactly what her experience is, and the particular and important knowledge and authority it has given her to speak on not only marriage, but also the role of women in society (she delivers a powerful critique of anti-feminist literature) and what women want the most (to have the sovereignty over their husbands).

It is this centering of experience as an authority that makes the Wife of Bath able to speak so easily in the voice of a “Kilburn girl.” In Smith’s retelling, this voice is Alvita, a Jamaican-born British woman who stands up at a pub night to tell the story of her five marriages and offer her philosophy on life, love, and the social status of women. By centering experience as a site of authority, Chaucer’s six-hundred-year-old character invites unique and particular experiences, ones distinct from the particularities of Alyson’s time, to be read into and through the Wife of Bath. She invites other experiences, other ways of knowing and understanding the world, to speak over and against known and established authorities.

What Smith does in showing the Kilburn girl located within the Wife of Bath’s voice of experience is to open up space for thinking through the particular authority—the particular value and, especially in the play’s conclusion, the particular forms of sexual justice—such experience offers. “Let me tell you something,” states Alvita in her opening lines, “I do not need / Any permission or college degrees / To speak on how marriage is stress. I been / Married five damn times since I was nineteen! / From mi eye deh a mi knee.” Smith transfigures medieval clerical authority here into college degrees, and she summons the specter of an unnamed but powerful ideological body that might weigh in—might offer permission—for Alvita to speak. Into and against this authoritative space, Alvita moves with direct forcefulness—“I do not need”—to insist on the particular authority of her own experience. Alvita shares with Alyson a source of authority (surely five marriages is sufficient here), but she frames that history in her own particular experience. This framing begins with the patois idiom “From mi eye deh a mi knee”—From back when my eyes were at my knees—that signals a knowledge she’s been acquiring since she was a small child, and it moves forward into one of Smith’s great innovations of the play: a series of various authoritative voices from Alvita’s own life, with whom she argues directly and powerfully. She dismisses with zeal her pious aunt, Auntie P; the megachurch preacher, Pastor Jegede, with whom she gets into searing theological debates about the value of virginity and sexual purity (Alvita is not about that life); and all five of her ex-husbands, whose jealousies and misogyny she gleefully squelches through remembered comebacks.

As satisfying as it is to watch Alvita wield her experience as a weapon, combatting sexual double-standards and insisting on the pursuit of her own sexual pleasure—and it is enormously satisfying—Smith’s most powerful work around experience and authority comes in the final section of the play, in which she moves from the Wife of Bath’s Prologue to the Tale. In its medieval form, the Tale describes how a knight rapes a young peasant and, as a punishment, is charged with discovering “what women most desire.” The end of the story and the Wife of Bath’s speech resolves in a fraught and complex mix that seems by turns both proto-feminist and anti-feminist. They conclude with a celebration of women achieving what they most desire (to have “sovereigntee”), even as that sovereignty also—conveniently for the tale’s rapist, a man—ends in a fantasy that would find itself comfortable in red pill forums (the protagonist, once he “learns his lesson,” ends up with a beautiful, youthful, eternally faithful wife).

Smith’s ending, however, offers something different, largely due to Smith’s re-centering of experience as an authority with a particular force when considering women’s lives and sexual justice. We can see this first in the way that Smith reframes the rape and the justice enacted after the fact. Smith transfers the setting of Chaucer’s tale from Arthurian Camelot to 18th-century Maroon Town, Jamaica, led by the powerful Queen Nanny, a “Famed rebel slave and leader of peoples!” Alvita narrates the events of the rape simply, with a series of telling pauses during which two characters re-enact the moment of violence:

![ALVITA: Anyway: our Queen Nanny Had a young buck Maroon in her army Who one day rode to Cudjoe’s Leeward Land, Where he saw a beautiful, young Akan Girl, early one morning, just walking by, We see this re-enacted by DARREN [Alvita’s second husband] and KELLY [Alvita’s niece]. A virgin, with no interest in this guy, But he wouldn’t stop. Pause. He thought his strength gave Him the right. Longer pause. Well, Cudjoe Town was outraged By this criminal oppression…](https://pshares.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Screen-Shot-2022-04-15-at-3.41.43-PM.png)

What in Chaucer is an important but brief reference to an act of rape is, in Smith, given space. She doesn’t add to the lines, but the pauses she inserts, the spaces between the lines of narration, carry a heavy weight, especially as the two characters mime sexual violence on the stage.

And it is with that weight that we then learn what sort of justice will be offered. The outraged people of Cudjoe Town demand death, but Queen Nanny intervenes and suggests justice of a different form:

Yuh nuh outta trouble yet! Mi might still

Kill you. But capital punishment will

Only go so far. I’m interested in

Restorative justice. Understanding

Who you hurt and why. So here is my deal:

You’ll live—if you can tell me what we feel—

I mean we women. What we most desire.

You tell me that? I won’t set you on fire.

The language and framing of restorative justice is telling: the task of discovering what women most desire—a riddle in Chaucer—becomes here a task of compassion, of seeking to know something of another’s experience. Capital punishment can only be evaded when the young Maroon is able to show that he has understood something about “what we feel.”

This understanding of experience holds true for the tale’s conclusion. In Chaucer, one of the reasons that the tale’s conclusion is so fraught is that, although the young knight learns the answer to the riddle, his answer is untethered from experience. Not only does Guinevere (the original Queen Nanny) not frame his task in terms of restorative justice, but in the conclusion, he doesn’t so much understand the answer as he wearily gives into it. The young knight is given the answer by an old hag who demands marriage as payment. When the two marry—with great reluctance on the knight’s part—the old woman offers the knight a choice: she can stay old and faithful or become young and disloyal. After listening to her lay out a complex and lengthy series of arguments, the knight eventually gives in and tells the woman that it is up to her to choose—a choice that, ironically, results in him receiving what he most desires: a young, faithful wife. The knight gets his happy ending, but he never has to understand the experience of the woman he raped, of his wife, or of any other woman.

Smith offers a different vision. Making critical use of the medium of drama, in her tale’s conclusion, the figure of the old hag, played by Auntie P, transforms not into an always faithful young wife but into Alvita. The young maroon becomes one of her husbands, Darren, and the scene ends with Alvita dancing to Chaka Kahn’s “I’m Every Woman” with all of her husbands. The transposition of Alvita in place of the old hag is a critical choice. It interrupts the masculine fantasy (Alvita is a fantastic character, but, she is not young, and she has never been exactly faithful), but, more than that, it recenters Alvita and her experience and vision of sexual politics and pleasure. We end with her celebrating her own vision of sexual pleasure: “Oh, Lawd Jesus Christ, forever / Send us meek, young husbands who are good in bed / And let us long outlive the men we wed!” It’s an irreverent and comedic end, as over the top as Alvita has been. But it’s also one that doesn’t undercut Alvita. It makes space for celebrating what is powerful, brash, irreverent, and scandalous about Alvita, the Wife of Willesden’s, experience.