People of the Book: Cherry Williams

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Cherry Williams, Manuscripts Curator at the Lilly Library at Indiana University.

1. How do you define a “book”?

I define a book as the vehicle or medium which transports ideas, thoughts, information and/or images across time and space. So, my definition of a “book” could include every kind of medium and format from clay tablets to scrolls and rolls, as well as the codex.

2. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading?

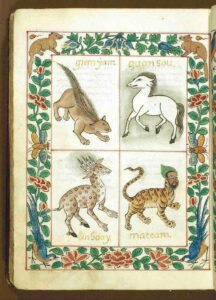

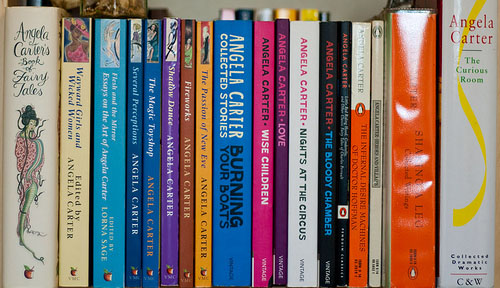

I engage with books all day, every day, in the course of my professional practice. As the Curator of Manuscripts, I deal with every kind of manifestation of a book in its becoming and being a finished artifact, from cuneiform tablets, to exquisite medieval codices, to handwritten and typescript drafts of contemporary poetry and literature, to artist’s books. I work with books in many different kinds and forms of physical aggregation and binding, as well as instances of materials which have become a “book” though they were never intended to be—such as elaborately bound collections of correspondence or ephemera. My work includes collection development, by buying new materials to add to the current collections, preparing materials for exhibition or exhibition loans, granting permissions for publications, and working with our conservators on questions of preservation and treatments, as well as teaching classes and providing visitors with hands-on experiences with our materials.

Probably like most of the people who will participate in this interview series, I have read voraciously throughout my life beginning at about age five, when I was told by my mother that I could get up early (around 5 a.m.!) if I sat and read quietly in the living room. My professional life in books, however, began in my first year of graduate school, when one of my instructors suggested that I visit the Special Collections Research Center on campus while seeking out a subject for a research paper proposal. As a result, I discovered medieval Books of Hours and the searching began in earnest. Since that time, in addition to self-directed study, internships, and independent studies, I have taken courses involving rare books, both in the U.S. and abroad, covering a diverse spectrum of topics from paleography to book construction and illustration to descriptive bibliography, as well as teaching graduate-level seminars on the history of the book.

3. What has been your most unusual interaction with books?

My more unusual or even remarkable interactions with books recently has involved dealings with donors, as well as when I hand-courier an object for exhibition loan. Sometimes we pick up donations on-site, doing the packing ourselves; not infrequently these interactions can have a degree of poignancy, particularly when a donor has spent a great deal of personal time and energy accumulating a collection. One donor kept his collection in his professional office and noted that the night before his collection was to be picked up he slept in his office to spend those last unrestricted hours with the materials. He would need to use the reading room to see them again.

When I hand-courier materials to an exhibition venue, there are often interactions with Customs officials, both U.S. and foreign, that can be both informative and sometimes time-consuming. For instance, one time an overseas customs officer was unable to clearly discern from my accompanying documents whether I was buying or selling this six-figure item rather than it being a statement of insurance value. These trips also offer the opportunity and pleasure to meet colleagues from other institutions and to learn first-hand about their collections and exhibition practices.

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

One of my favorite tidbits is the knowledge that underneath nearly every illumination is the breath of the illuminator or artist, who gently blows on the underlying gesso in order to warm and moisten it to accept and secure the gold leaf as it is placed on top. Medieval book production is such an organic process, whether roughhewn or refined, that the mark of the maker(s), so to speak, is always evident and endlessly engaging.

5. What material part of the book interests you most?

With manuscript books, the material part which interests me the most is really the physical construction of the book, the binding, etc.—i.e. all of the codicological information the object exemplifies. With print items, it is the construction of hand-casted type and the creation and development of font types, as well as the amazing proficiency of workers who hand-set the type. The ingenuity and craftsmanship is astounding.

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

I would grab one each of my grandmother’s and mother’s annotated cookbooks and my diaries, for all of the obvious personal reasons.

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

There are many things, but perhaps the most global is what a book represents around the world in cultures that have a history with the book, manuscript or print. I am so enmeshed with both the digital and the physical book that I see them as completely intertwined now. However, I have yet to meet someone who wants to read even the latest fiction work on a screen enmeshed in their glasses. Whether via Kindle or hard copy, people still want a tangible object to hold in their hands. Because I work with rare or special collections materials, and with students from K-16 as well as graduate students, my colleagues and I find that most of our students are captivated by the physical object of rare or unique books, old or new, and want the physical experience of handling a book that has a history: how was it created, its provenance, annotations, etc.? What is the distinctive history of this object?

A colleague and I are engaged in working with classes of third-graders (over 200 to date) to introduce them to the construction of the medieval book, familiarizing them not only with the use of digital surrogates in their home classrooms, but also providing them with a hands-on experience with the physical object itself through visiting the Library. This opportunity to teach “artifactual literacy” to young students—to introduce them to primary sources, as well as to the critical thinking skills necessary to evaluate a digital object vs. the actual physical object—is crucial to the nurturing of communities that continue to value the book and understand the book as an object of cultural production.

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

Anywhere; I am omnivorous. One of my favorite giveaways used to be leaving books I had read on trains, etc., but that seems to be a diminishing practice.

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

Thoughtfully, inventively, and creatively, I hope, and in ways in which the greatest numbers of communities can be engaged. In addition to our work engaging local third-grade students with medieval manuscripts in the Lilly Library, I also teach a History of the Book to 1450 course for the library science program here at IU, as well as an Introduction to Manuscripts course. Additionally, I am actively involved in curating our artist’s book collection so have the pleasure of interacting with pretty much every conceivable kind of manifestation of “the book,” including electronic, audio and digital. Combined with other programs and outreach services which we routinely offer here at the Lilly, I am always struck by the engagement of our participants with the book as an object of pleasure and joy. While each of these communities may vary widely in what they need or expect a book to be or to deliver, the notion of the book as a container or carrier, the actual essence of a book, seems to me to have retained its permanence as well as its significance as is demonstrated by communities and societies continuing to return to the book across the millennium as a recognizable and trusted format whatever its actual physical form.

10. What question do you wish that I had asked related in some way to books? Ask, then answer it.

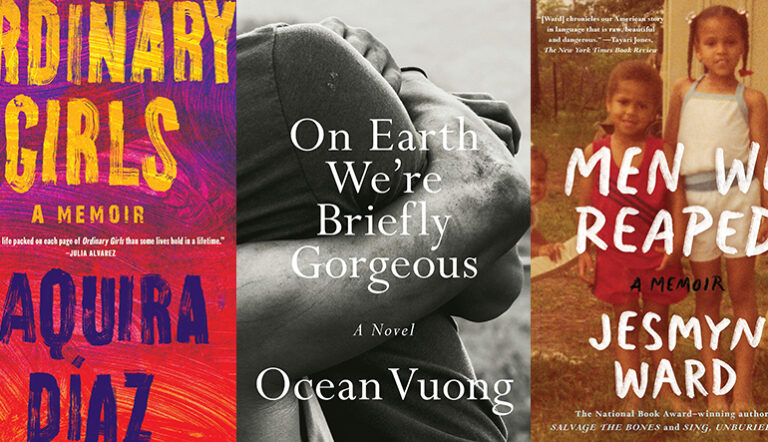

- Q: How is the authorial creation of the content of contemporary books changing? With the omnipresent use of computers in the writing of a book, how we will see and follow an author’s creative and possibly collaborative processes? How will this be documented and saved for future generations of researchers and scholars? Are we going to save every file, email and hard drive?

- A: I don’t have answers to these questions, but they are significant concerns for those of us who collect contemporary writers.

______

Cherry Dunham Williams, curator of manuscripts, has been with the Lilly Library at Indiana University, Bloomington since 2009. Before coming to the Lilly, she was Special Collections Librarian for the Sciences at the UCLA Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, History and Special Collections for the Sciences from 2007-2009. In addition, Ms. Williams is an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Information and Library Science, where she teaches classes in the History of the Book and manuscript studies as well as a member of the core faculty of MEST, the Medieval Studies Institute program at IU. She has completed rare book school course work at the London Rare Book School at the University of London, CALRBS at UCLA and the Rare Book School of Virginia, where she was recently awarded her Certificate of Proficiency in the Specialized Area History of Medieval & Early Modern Books & MSS. Currently, in collaboration with a Lilly colleague, she is engaged in developing outreach programs to introduce K-8 students to medieval book production and the use of primary sources as well as digital surrogates for the study of medieval manuscripts.