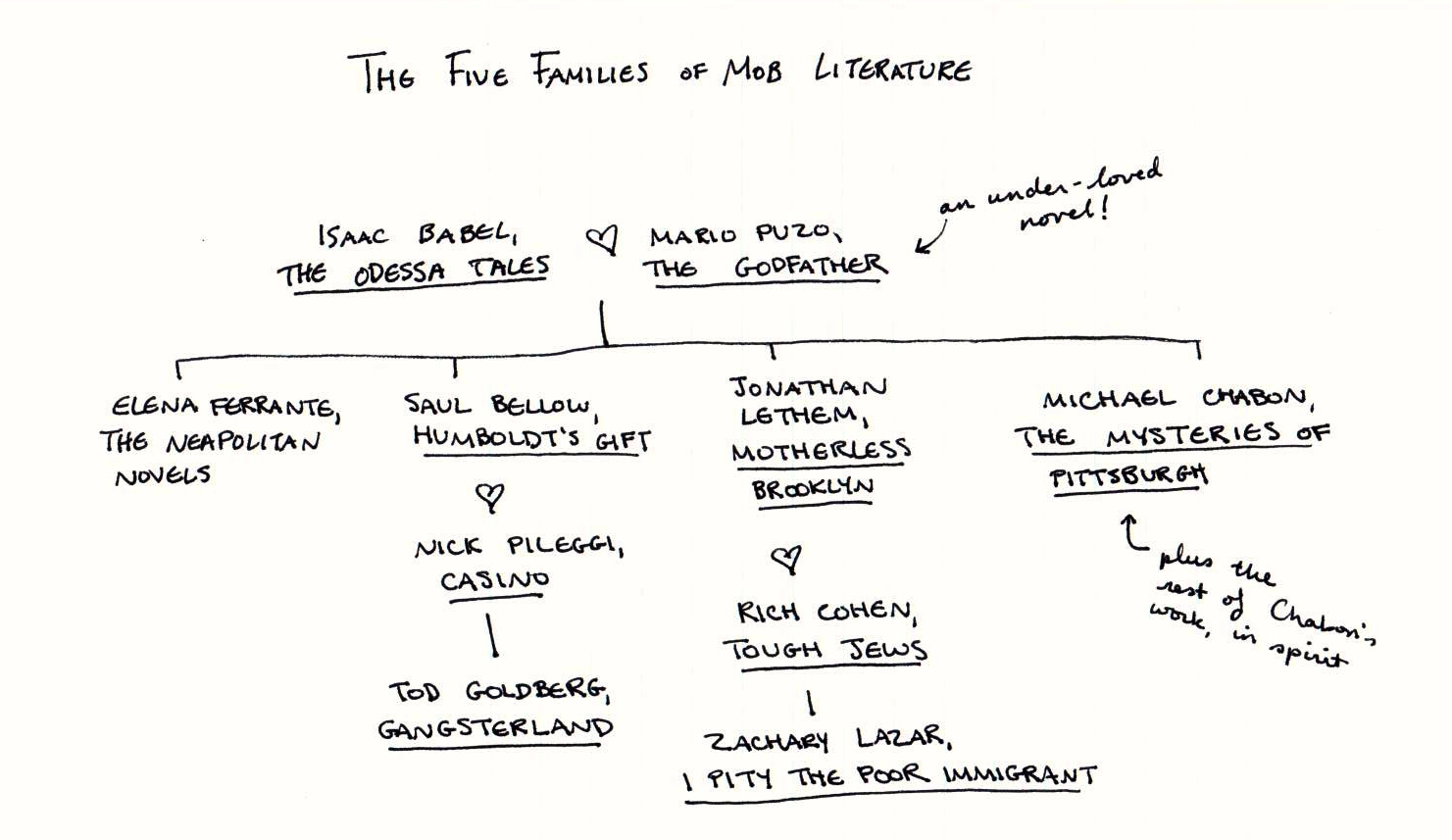

The Five Families of Mob Literature

There aren’t many books that are the best. I have favorites; we all do. Awards committees and English departments do. There are classics and The Best American Short Stories and all the rest, but how many books can you say, without second-guessing yourself, without blushing or adding, “I think,” are the best of their type? It takes a very specific type, as far as I can tell. The Western novel, for instance. Lonesome Dove, by Larry McMurtry, is the best Western out there, and I’m going to write about it soon enough. But this is my first Literary Family, and I want to start with books about families. Well, Mafia families. And no one has ever written a better Mafia novel than Mario Puzo’s The Godfather.

The writing is beautiful, first of all. Every sentence is clear and elegant, not a word out of place. Second, the characters are wonderful, and very well drawn. I’m the only person in the modern world who read The Godfather before I saw it, and when I finally watched the movie my first thought on seeing Al Pacino in his army uniform was, I know you. But here’s why The Godfather is not just good, but the best: Mario Puzo takes all the big themes of American literature, all the contradictions of the American dream, and makes them an exciting read. The Godfather is about religion and immigration, family and money, tradition and change. It’s about service and loyalty, and it’s about getting what you want and fuck everyone else.

Isaac Babel’s Odessa Tales is smaller and looser, a freewheeling group of interlocking stories that center on Benya Krik, the King. Unlike the Corleones, Benya works on a regular-human scale, one we can understand. He doesn’t make great sacrifices. He’s not trying to rule New York. He’s a literary character, and The Odessa Tales is literary fiction, linked short stories before they were cool. In fact, as far as I can tell, The Odessa Tales is the beginning of literary crime.

I’ll admit that Humboldt’s Gift isn’t a crime novel. Saul Bellow writes about men coming to terms with their own minds, not with the need to whack rival mob bosses. But Charlie Citrine, the protagonist, spends much of the book evading a Chicago gangster named Rinaldo Cantabile, to whom he owes money, but who mainly wants to be his friend. Cantabile is inescapable, and that is one of the great themes of Mob literature. Once you’re in, you can’t get out. Your boss, your family, your crimes—there’s always a shadow in a Mafia novel, creeping behind the main character, waiting to pounce.

In Nick Pileggi’s Casino, that shadow is Tony Spilotro, Lefty Rosenthal’s unreliable, too-aggressive best friend. (That’s Nicky Santoro and Ace Rothstein, respectively, in the movie.) In Gangsterland, Tod Goldberg’s new novel, Las Vegas rabbi David Cohen can’t escape the fact that he was once Chicago hit man Sal Cupertine—or the FBI agent hunting Cupertine down. The Camorra is a constant presence in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, though the main characters, Elena and Lila, treat the camorristas in their neighborhood as an annoyance more than a threat. Art Bechstein, the protagonist of Michael Chabon’s debut The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, is annoyed as hell at the Mafia, too—or, to be specific, he’s annoyed at his father, the gangster.

And then there’s Motherless Brooklyn, by Jonathan Lethem. It’s not good to play favorites in families, but Motherless Brooklyn is my favorite. There’s more Mafia in Lethem’s novel than Chabon’s, more wordplay than in Humboldt’s Gift, more New York than in The Godfather. I can’t read Motherless Brooklyn in public because it makes me laugh too hard, and then it makes me cry. Not well up, either. I’m talking big, fat tears. It’s the story of a fourth-rate Tourettic mobster on a quest for his boss’ killer, his only clue a joke about the Dalai Lama’s Jewish mother, and it is as beautiful as it is innovative.

Pair Motherless Brooklyn with Rich Cohen’s first book, Tough Jews, a nonfiction account of the Jewish mob in America, and you get Zachary Lazar’s I Pity the Poor Immigrant, a three-pronged, highly empathetic dissection of the Mafia banker Meyer Lansky’s old age. (Remember Hyman Roth in The Godfather Part II? Okay, you know about Meyer Lansky.) I don’t know if Lazar read Cohen or Lethem. I don’t know if Tod Goldberg thought about Humboldt’s Gift when he was writing Gangsterland, though I don’t know how he could write a Mafia novel set in Las Vegas without reading or watching Casino. But I think these books go together. I think they’re in one big conversation about self-determination and toughness and who exactly is a good guy, and I think it’s a conversation worth having.