Do-Overs: Summer Odyssey

Each June, my thoughts turn toward home. Toward my kids, bare feet, homemade dinners, and naps. Toward real life. I’ve taught high school for 13 years, I’ve learned to ride the waves of feeling that come during each season of the school year. June means home, and as my attention changes, I tend to search out comfort in familiar stories—stories of homecoming.

Each June, my thoughts turn toward home. Toward my kids, bare feet, homemade dinners, and naps. Toward real life. I’ve taught high school for 13 years, I’ve learned to ride the waves of feeling that come during each season of the school year. June means home, and as my attention changes, I tend to search out comfort in familiar stories—stories of homecoming.

Why is the homeward journey archetype so easy to love? Think of Forrest Gump or the Wizard of Oz, or even Toy Story—a character’s return to home is a return to safety and comfort. Familiarity. The known world. This return isn’t without complication—generally, the hero returns changed. (Paging Carl Jung!) But he returns. When it’s the end of a term and my world is about to shrink to only my nuclear family, I long to steep in these homecoming narratives. Ideals of hearth and acceptance, calling to the embattled hero. These stories where characters fight to return home are endearing because they call upon such familiar feelings. They align with our sense of stability—or our desire to get to a peaceful place, to do what it takes to return.

Stories of Prodigal sons and daughters offer rich possibilities for writers—not from the perspective of characters who return home, but those who never left. As Greg Jackson, author of a forthcoming collection, Prodigals, said in a 2014 interview with The New Yorker,

In the Bible, we aren’t given an account of the son’s motives or of the decadent years in which he exhausts his inheritance. I suppose I like to think that he couldn’t bear the plodding labor of working on his father’s estate, with only the staid and predictable continuation of the family line and business to look forward to. He wanted something more. […] My interpretation of the prodigal spirit is a broad one—yes, at times it’s wasteful and disloyal and insensitive to others, but it’s also driven by unanswerable longing and by an inability to fit neatly into the life that was limned for you at birth.

What if home isn’t everything we remember it to be? Such is the case in Barbara Kingsolver’s novel, Animal Dreams. What does it say about us if we don’t trust our recollection of what we think we know for certain? “Memory is a complicated thing,” Kingsolver famously wrote, “a relative to truth, but not its twin.” Kingsolver’s work twists ideas of perspective and mental stability—when Cosima returns to care for her ailing father Homero, she has to let go of her definitions of home, family, and herself. Even stories of difficult homecomings are good ones. They evoke same yearning.

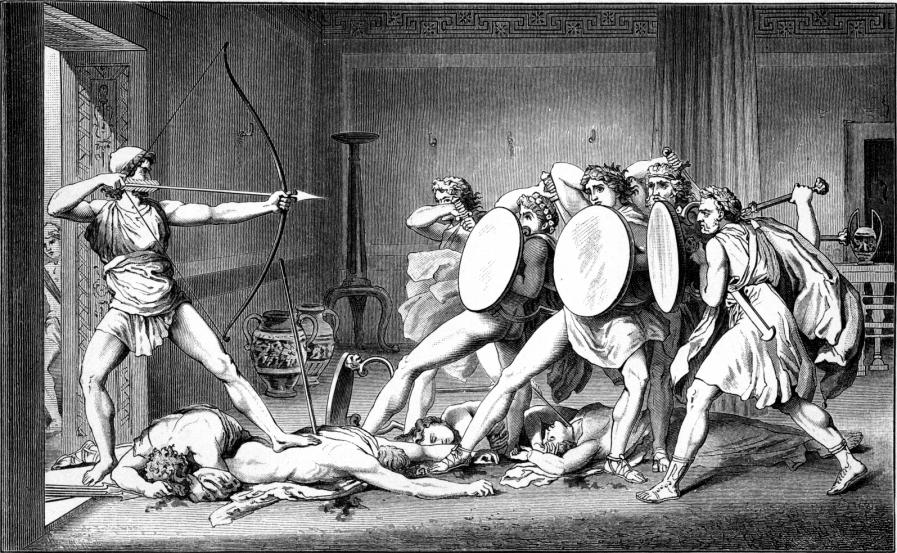

It would be impossible to discuss the archetype of the journey home without mentioning our pal Odysseus. (Lionsgate is apparently at work on a new film adaptation of the classic.) The hero fights his way past various baddies to return home to his family and dog. (It’s fitting that Homer’s hero’s arrival includes a touching moment with the dog, too—who better to greet you at the door after a long journey?) The Odyssey has been redone countless times. Tennyson’s “Ulysses,” Joyce’s Ulysses, the Cohen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Image Comics’ “ODY-C,” a “gender-bent, eye popping, psychedelic science fiction Odyssey” featuring “Odyssia, the clever champion.” Odysseus still works, especially if he’s a she, in space.

But my favorite homecoming story, the guiltiest of pleasures, is also one I return to with predictable regularity. I started watching Star Trek: Voyager in the 90’s. Is it campy? Yep. And delightful. As a homebody, I prefer stories where the hero returns more than the ones where the hero sets off an adventure. I go back to Voyager, and books like Kingsolver’s Animal Dreams when—as now, at the end of the school year—I need comfort from my entertainment. Sometimes we need to look ahead. To set a course for home.

image: 1888 engraving featuring Odysseus as he slays Penelope’s suitors. He can’t even catch a break at his own door.