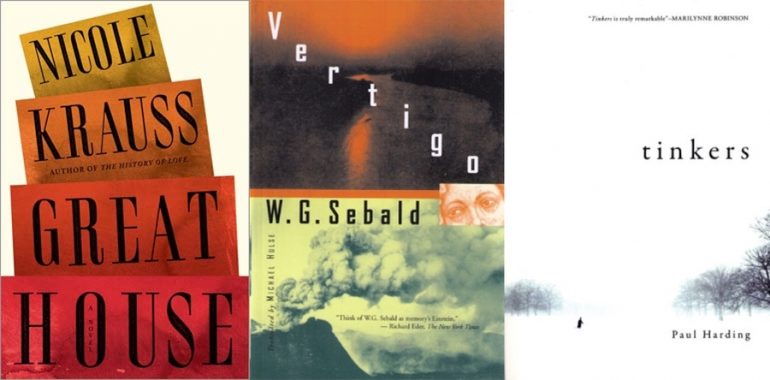

Writing the Mind: Nicole Krauss, W.G. Sebald, & Paul Harding

How does one apply the adage show don’t tell to the interior of the mind—a vast expanse one inhabits daily, but never sees? While Pixar’s Inside Out turns the subconscious into a playful and sometimes dark adventure, literature must rely on language—pacing, syntax, and form matching function.

In the early pages of Nicole Krauss’s novel Great House, Nadia mentions to an unnamed character that when her significant other moved out, she was left with little. A friend suggests she call a Chilean man who was searching for a place to store his furniture while he traveled back to Chile. Krauss writes:

“It took a minute for him to sort out who I was, a minute for the light to go on revealing me as a friend of a friend and not some loopy woman calling—about his furniture? she’d heard he wanted to get rid of it? or just give it out on loan?—a minute in which I considered apologizing, hanging up, and carrying on as I had been, with just a mattress, plastic utensils, and the one chair.”

Rather than being told that Nadia is nervous, or having Nadia state, I was nervous, Krauss utilizes pacing and language to convey anxiety. Similarly, the word “loopy” mirrors the looping, spiraling structure of the sentence, and heightens the repetition of words and phrases, such as “a minute,” and “a friend of a friend.” The three questions embedded in the sentence, one after another, rapid-fire, suggest the firing of synapses in an uncomfortable exchange—when one’s mind and mouth are trying to sync up, make sense, or be understood. Not only are there three questions, but three mentions of “a minute,” conveying how quickly this all happened, but how long and drawn out the exchange seemed to feel. Likewise, Krauss pairs three verbs—apologizing, hanging up, and carrying on—and three nouns—mattress, plastic utensils, chair—to create a winding, well-rounded sentence.

The form matches the function; the structure of the sentence conveys the rushed and uneasy nature of the phone call, without explicitly stating what was said between them, or the tone of voice, or the external details or gestures that were made in those quick moments. We are wholly embedded in this character’s mind. We are intimately woven into their internal landscape, at once cerebral and emotional.

Krauss’s fiction often deals with the subject of memory, as does the writings of W.G. Sebald, whose themes include memory and decay. The second part of Vertigo, “All’estro,” follows an unnamed narrator on a winding journey from England to Vienna, Venice, and onward. The account sways from the narrator’s internal thoughts to the external world around him, and his mental state deteriorates, until, in Venice, he laments:

“It seemed to me then that one could well end one’s life simply through thinking and retreating into one’s mind, for, although I had closed the windows and the room was warm, my limbs were growing progressively colder and stiffer with my lack of movement, so that when at length the waiter arrived with the red wine and sandwiches I had ordered, I felt as if I had already been interred or laid out for burial, silently grateful for the proffered libation, but no longer capable of consuming it.”

The narrator sets forth a kind of thesis in the first line: one could end their life through thought and retreat into the mind. Rather than explaining this, Sebald turns to the exterior, to the windows and the temperature of the room, the body, and the waiter. Through observation of the external world, we understand the cerebral landscape Sebald is attempting to convey. The character is unable to move for days, and the sentences that describe those days are equally still: “The crimson dusk gathered above the lagoon, and when I awoke I lay in deep darkness.” Finally able to get up, pack, and leave, the new feeling of movement catalyses the narrator’s thoughts, so that readers are given a series of lengthy sentences describing the buffet, of all things:

“The buffet at Santa Lucia station was surrounded by an infernal upheaval. A steadfast island, it held out against a crowd of people swaying like a field of corn in the wind, passing in and out of the doors, pushing against the food counter, and surging on to the cashiers who sat some way off at their elevated posts. If one did not have a ticket, one had to shout up to these enthroned women, who, clad only in the thinnest of overalls, with curled-up hair and half-lowered gaze, appeared to float, quite unaffected by the general commotion, above the heads of the supplicants and would pick out at random one of the pleas emerging from this crossfire of voices, repeated it over the uproar with a loud assurance that denied all possibility of doubt, and then, bending down a little, indulgent and at the same time disdainful, hand over the ticket together with the change.”

As the narrator surveys the crowd he sees them as a “circle of severed heads.” Not only that, but “the eyes of two young men were” fixed on the narrator, men he recognizes from another bar in another city, and he responds with a flash of fear, quickly finishes his cappuccino, walks to the train platform, and glances over his shoulder a few times before boarding the train.

Sebald does not need to explicitly state that the character is experiencing mental distress, as reading the above passage gives this reader the same feeling. As with the excerpt regarding ending one’s life through thought, the topic of death arises, this time over something as seemingly trivial as possessing a scrap of paper one needs to order food. Before mentioning death, Sebald’s description of the cashiers, “at their elevated posts,” “these enthroned women,” “appeared to float,” “above the heads of the supplicants,” “indulgent and at the same time disdainful,” is then juxtaposed with the male employees who “faced the jostling masses with withering contempt.” Yet both the men and women “resembled some strange company of higher beings sitting in judgement.” It’s as if the narrator had died in that hotel room, and now faced the gates of heaven or hell in the train station’s cafe.

“Surrounded,” “circular,” and “circle;” the words embedded in these long and winding sentences mirror the pacing and structure, while indicating the internal landscape of the narrator. If one did not understand what was meant by the previous statement of ending one’s life through thought, one sees the unraveling, the possibility of coming completely undone.

We witness another kind of undoing in Paul Harding’s Tinkers, as Howard suffers severe seizures. Prior to, sentences are elongated, as the character loses track of time. A mental shift occurs, not plainly stated, but shown through the observance of the outside world and the sentence structure:

“The field was an abandoned lot. The remnants of an old house, long since fallen into ruin, stood at the back of the field. The flowers must have been the latest generation of perennials, whose ancestors were first planted by a woman who lived in the ruins when the ruins were a raw, unpainted house inhabited by herself and a smoky, serious husband and perhaps a pair of silent, serious daughters, and the flowers were an act of resistance against the raw, bare lot with its raw house sticking up from the raw earth like an act of sheer, inevitable, necessary madness because human beings have to live somewhere and in something and here is just as outrageous as there because in either place (in any place) it seems like an interruption, an intrusion on something that, no matter how many times she read her Bible, Let them have dominion, seemed marred, dispelled, vanquished once people arrived with their catastrophic voices and saws and plows and began to sing and hammer and carve and erect. So the flowers were maybe a balm or, if not a balm, some sort of gesture signifying the balm she would apply were it in her power to offer redress.”

Wading through beautiful language as Howard wades through the lagoon of his own mind, the reader comes to realize as the character does that his seizures are triggered by a revelation, a consciousness, or insight which he can not grasp because he is immediately swept away. Harding, through Howard, is attempting to explain the unexplainable, the way the mind works before it teeters too far to an extreme. Though Howard’s wife and son see his seizures as a shameful illness, only witnessing the external effects, Howard himself expresses the phenomenon as a transcendent experience—mirroring historical splits between viewing seizures as an incredible gift or a damning curse. He can’t, or doesn’t, access this transcendence through manmade objects, like the ruins of the old house, or the words in the Bible, but through the flowers, “maybe a balm.”

Writing the mind in an implicit way, utilizing language to show but not tell, often gives way to the fortunate byproduct of beauty. Not embellished to the point of being ostentatious, but similar enough to the way the mind works to be plausible. Like fingerprints, the way we think and learn are unique; stepping into the pages of another’s consciousness, embedding oneself in their intellectual and emotional processes, we may learn how others think or feel, a first step toward empathy. Occasionally, there is the uncanny resemblances to our own minds, where we are left with both the sense that we are and are not alone with our thoughts—at once refreshing and strange.