The Follow Up: Jennine Capó Crucet

I’m going to be talking to a few authors whose first books I admired and see what they’re working on in terms of a second book. One of the things that interests me here is how writers move from a shorter form to a longer one. Talking about the process while in the process is something I don’t see a lot, and I’m sure some writers would hesitate to do it. I have, however, found some brave souls willing to discuss their work, past and present.

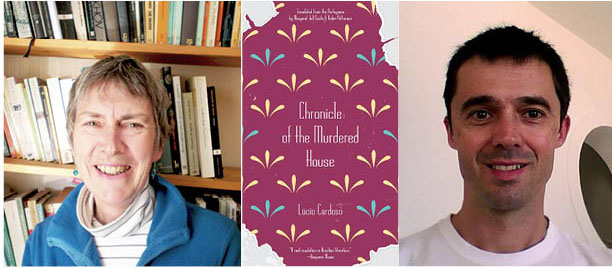

I met Jennine Capó Crucet at the Chicago AWP conference in 2009. I am not a good flyer, and so I was pretty groggy and out of it as we shared a cab from the airport to the hotel. I remember thinking, “What the hell is this woman talking about?” It all came very fast, especially to someone on Dramamine. I knew two things about her: she had won the Iowa Short Fiction Prize, and I had read something of hers somewhere. Later, when my head had cleared, I remembered she’d published a story in Ploughshares that I had loved, a lightning bolt of a piece entitled “Resurrection,” in the Ron Carlson-edited 100th issue.

When How to Leave Hialeah, her debut collection, came out shortly thereafter, the reviews were glowing. It won the John Gardner Book Award, the Devil’s Kitchen Award, and was honored as a best book of the year by a variety of publications. Like a lot of my favorite books, How to Leave Hialeah walks the line between humor and heartbreak, giving you enough of one to then pull the rug out from under you with the other. Jennine’s sense of voice is so clear and committed that the stories beg to be read aloud, something she does as well as anyone. At a reading she gave at MIT, people would be moved from laughter to stone silence in a moment, as Jennine led them through the hairpin turns of the experience of a Miami teen’s first days of college.

As the conference went on, and now the years have passed by, I’m still not entirely sure what she’s talking about, but I definitely listen. And I stay away from the Dramamine.

Jennine was kind enough to sit down and answer some of my questions about following up her collection with a novel, as well as the short story form, reading aloud, and boxing up failure.

James Scott: How much did you try to do with your collection before winning the Iowa Short Fiction Prize? Had you sent it to agents and editors?

Jennine Capó Crucet: I hadn’t tried to do much with it, honestly. I knew it was a book, but I didn’t have an agent, and the ones I’d heard from (those that contacted me after reading a story of mine in Ploughshares, actually) kept asking if I had a novel – they said that they loved collections, but there was no market for them – same old story. I kept hearing, “I LOVE collections, but they don’t sell.” So my plan was to wait until I had a novel finished, then sign on with someone and hope for that magical two-book deal. But it was sad for me to think of my collection that way – as some bonus or mutant appendage to a novel rather than something worth publishing on its own – so I started looking into long-standing contests that really honor story collections as a form. I wanted my book to be part of some big tradition, to be part of some family of collections that had all been handled with respect and care. The book ended up winning the Iowa Short Fiction Award, and since their press gets behind two collections a year, they have a lot of love for the book. And since they read blindly, I knew it was the book winning the prize. I’ve really enjoyed being part of the Iowa family – they really show story collections some love.

JS: I have finally found a title for my future undergrad class: Short Story as Mutant Appendage. As Don Waters can also attest, Iowa does some amazing work. You’re in phenomenal company.

You’re working on a novel as a follow-up. What can you tell us about it?

JCC: Not a whole lot because I worry a little about jinxing things when they’re going well, but it’s largely based off some of the themes raised in my book’s title story, “How to Leave Hialeah.” It’s set in both Miami and New York in 1999-2000, around the time the Elian Gonzalez ordeal was unfolding. The protagonist, Lizet, is the first in her family to go to college – she’s the first in her family to graduate from high school, too – and she’s struggling enough as it is when her whole first year gets abruptly politicized both at school and at home. Despite the political drama she’s struggling to avoid, I imagine the book to be this fictional road map of the first-generation college student’s experience, one that shows some of the ugly things class differences force on us, but that also shows how we can push through them somehow. About four months into the writing, I found out that the story had won an O. Henry Prize, which I took as a sign that my gut was right in thinking there was more to that story than the story.

JS: Do you have attempted novels in a drawer or is this your first try?

JCC: There are two novels in a drawer (or, actually, a box) – one finished and one abandoned. One – the one I’m calling “finished” – I began in the last year of my MFA program and was overly ambitious. It has the structure of a train wreck and has four different narrators and spans seventy something years and parts of it are entirely in Spanish because I had some weird ideas about “excluding the reader in order to evoke empathy” or some crap like that. It was crazy. I was thinking too much about ideas and not enough about character. The central story is, I think, actually really compelling and there are about a hundred pages there that I hope to return to one day when the current book (and the one after that, which is already brewing in my head and heart) is finished. The other attempt is a novel that I began for the worst reason – one my then-agent thought they could sell, based on a “This Recognizable Character” meets “That Best-Selling Plot” kind of thing. I never finished it, and we amicably parted ways soon after that. But I learned a lot from both projects, and the fact that this novel has felt so different from the beginning is a great, great thing.

JS: I think most of us have those boxed novels. It’s strange to keep them around, I guess, but you don’t want to just chuck this weighty evidence of your own work. Or maybe it’s the weighty evidence of how things can go wrong? I guess it depends on what drives you.

The collection features such strong voices, and such a huge range of emotion – did you find the voice for the novel quickly, or did you circle it for a while?

JCC: It’s hard for me to explain this, but the new book kind of came to me almost fully formed one afternoon in March of 2010. I was sitting in a meeting as part of my then-job at a non-profit as a full-time college counselor to a group of first-generation college kids. Every single one of them was from a low-income family, was about to be the first in their family to go to college, and was also bright as hell. And then one girl – one very dear to my heart – started crying and saying she wasn’t really smart enough to go to the ridiculously exclusive and awesome college that had accepted her. And then, as she went on about her fears and her sense that she was only admitted because they needed brown people, all the other kids in the circle started nodding their heads and saying they felt the exact same way, and I was immediately thrown back ten years to myself at 18, having the exact same fear, and I lost my shit. All that dark horribleness rose up out of me – I barely made it through that meeting – and I started writing that night. The narrator’s voice came to me immediately (and this only really happened to me one other time, with my story “Men Who Punched Me in the Face,” which I wrote when I had a fever of 102 and was pretty much delirious), and it was urgent – and it finds me every day, yells at me when I’m not working hard enough. It’s a blessing and a curse.

JS: That’s incredible. I think anyone, after hearing that story, would also yell at you to get this thing finished.

I wonder because of your background in comedy and your wonderful reading presence how reading aloud plays into your writing and editing process. Again, your voice is so strong, and for it to appear so natural must take a lot of work and revision. I think people see and hear that voice, and they don’t see the bolts and screws and seams that have been smoothed over and covered up with revision.

JCC: Thank you! And yes, I totally read aloud as I revise. There’s so much clunkiness and phrasing that sounds good as it leaves my hands, but then doesn’t really represent my characters accurately, even if it’s how they might really talk. Working as a sketch comedian taught me a sense of timing, and I’ve learned that that timing has just as much a place in something serious as it does something funny. And my work is really attempting to capture a particular sound and flavor of speech – Miami, young, somewhat aggressive, somewhat unrefined – and that takes a lot of work to get right. It would be easy to throw a lot of profanity in there and say, Close enough. It would be easy to just write simple, declarative sentences. But that wouldn’t be right. When it gets down to revision, down to making the voice as precise as possible, I try to be like the poets: I’m working on words. I’m asking commas if they need to be commas, or should they be dashes? I’m reading sentences out loud over and over again. To stand outside my office door when I’m writing is to think you’re listening to a crazy person.

JS: I’ve asked people a lot about their connection to place. In fact, your stories seem to blossom out of place – the connection and disconnection one can feel with home. What role does setting play in the novel?

JCC: It plays a huge role – and I think Miami as a setting always will, since that city made me. The main character in the novel is constantly yearning to be somewhere else, to find where she can be who she’s meant to be. When she’s in New York, Miami seems like paradise, and when she’s in Miami, she can’t find a moment quiet enough to think in. When she’s on campus, she feels more Cuban than ever, but when she’s back home, she feels like the most American thing for miles. And for first generation college kids, this is bigger than homesickness – home can feel like a place where the new person they’re becoming just isn’t welcome. And they don’t always feel welcome on their campuses, in their classrooms. So the setting in the book is vital in the sense that the character is actively creating and reinterpreting it for herself at every turn. In some ways, the setting is the story.

JS: Do you think working on stories was necessary training for you?

JCC: Yes and no. I think stories spoiled me a little in that they could be a complete thing much faster. It was sort of like not eating all of your dinner but still getting to eat dessert. But writing stories taught me how to cook that dinner in the first place, right? This metaphor is falling apart. What I mean to say is, writing stories helped teach me all the things I’d need to do to tackle something larger, but they didn’t prepare me for the long haul that is writing a novel. I think the biggest gift writing stories has given me, though, is that when a novel has hit me, I was able to see – to tell almost right away – that it wasn’t a story. I know what a story looks like, and when those bigger things drift over me, I can recognize them as something huge, as something ready to demand much more of me – as something else entirely.