Cartoons & Archetypes: How They Work and What to Know

I learned about character development not by studying it, but by understanding the nature of cartoons. I spent years sculpting superheroes and cartoon characters for DC Comics, Nickelodeon, Pixar, and others.

Although the perception is changing, the art world considers cartooning of all kinds to be a distant, lesser cousin to the fine arts, painting and sculpture. But consider what the cartoonist must do:

First, the artist must be able to recognize the essential features of their subject. Whether it be a facial expression, a scene between two characters, or a gesture, the artist has to clearly identify what makes those traits distinct and readable.

The artist then has to capture the nature of those traits by performing two seemingly opposing actions: amplifying them and simplifying them. And all of this must be done with as few lines as possible.

A cross-pollination of literature and visual art, cartooning has its origins in both. The earliest language was made up of hieroglyphics, stylized pictures of the objects they represent. The earliest narratives were conveyed through simplified drawings strung together in cave paintings.

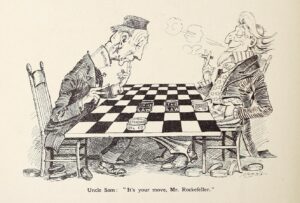

We perceive cartoons as both language and art. Consider the cartoon in this post. We experience the image as we would a painting, as a whole and all at once. But the details of it come together to tell a linear story—Uncle Sam has Mr. Rockefeller cornered. We know this unequivocally, because the body language and facial expressions of the characters tell us so. These depictions of smugness and bewilderment are universally recognizable because they are familiar to us; we have seen them many times before.

When characters and their traits are familiar, we need less information to understand them; we can fill in the details ourselves. The mind’s eye can more easily conjure up familiar images and subjects than unfamiliar ones. UC Berkeley created videos of brain images that demonstrate this process.

We are hardwired to understand the language of archetypes and cartoons because it taps into the collective unconscious, the inherited part of the human psyche not associated with the individual self, but an ancestral archive of symbols, images, expressions, and mythology that make up the fundamental road map inside all of us.

The art world too often dismisses cartoons as simplistic, but according to Carl Jung, “There is good reason for supposing that the archetypes [cartoons] are the unconscious images of the instincts themselves, in other words, that they are patterns of instinctual behavior.”

For this reason, cartoons are efficient, effective and powerful communicators. After all, a cartoon nearly sparked a holy war when Charlie Hebdo published a satirical depiction of the Prophet Muhammad.

As with the way a cartoon is constructed, a literary archetype is created by amplifying and simplifying certain universally familiar character traits. The literary world sometimes mistakes what is archetypal as cliché. It is easy to create a character who is a unique individual, but characters who are not also quintessential are difficult to empathize with. Characters who aren’t in some way archetypal are like discordant, atonal songs — there is nothing familiar for the audience to grasp.

Consider, on the other hand, these characters in literature: Ignatius Reilly, the slovenly fool in John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces; the shrewish grandmother in Flannery O’Connor’s A Good Man is Hard to Find; and the everyman hero Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird.

These characters endure not despite being archetypal, but precisely because they are.