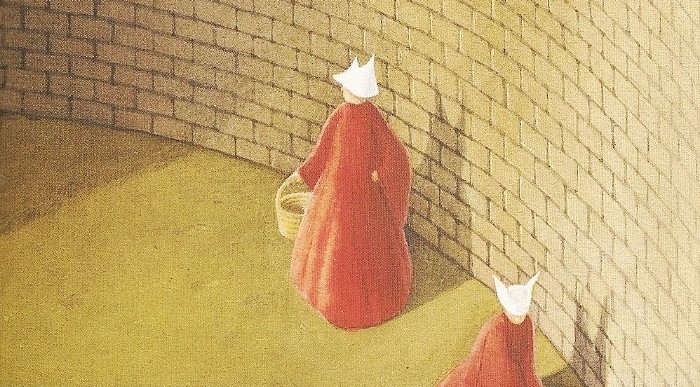

Throwback Thursday: The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Throwback Thursday is a series that highlights classic texts commonly assigned to students that deserve to be revisited and reconsidered in adulthood. This month’s selection is The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood.

Margaret Atwood has always asserted that her work isn’t science fiction: instead, she has always insisted that it be classified as speculative fiction. Defined by the author as the “things that really could happen but just hadn’t completely happened when the authors wrote the books,” in 2017, it truly does feel that this is the correct way to group her novels and stories, as they move further from fiction and closer to the reality that we know now.

Case in point: The Handmaid’s Tale. In an op-ed on March 10th, Atwood wrote, “Back in 1984, the main premise seemed—even to me—fairly outrageous. Would I be able to persuade readers that the United States had suffered a coup that had transformed an erstwhile liberal democracy into a literal-minded theocratic dictatorship?” The answer, both at the time of publication and in today’s Trumpian reality, is yes. And the novel, which spent the better part of the last four decades being assigned to high school students across the country as summer reading, is more important than ever.

The Handmaid’s Tale takes place in the Republic of Gilead, the totalitarian state that has come to replace the United States we know today. The group that has overthrown the government, the Sons of Jacob, consists of Christian fundamentalists who quickly dismantle all of the rights and freedoms we hold most dear and segregate out all members of society into functional castes based on gender and abilities. Our narrator is never named officially, but we come to know her as Offred—and it’s through her eyes that we see both the rise of Gilead, developed through flashbacks, and the tortured life that emerges once the new regime has been installed.

Offred was raised by a single mother, a well-known feminist activist who instilled deep principles in her daughter. We learn that our narrator had an affair with a married man, and bore a child—and despite the fact that the man would later leave his wife and marry Offred, their marriage becomes invalid in the new set of rules employed in their society. She is separated from them, from the world she knows, and forced into sexual slavery in the first generation of women to serve in the role of Handmaid.

There are several different classes of women that emerge in the new caste system, namely “legitimate women” and “illegitimate women.” “Handmaid” is the term that’s used for women who are able to reproduce in a society of dangerously low fertility rates, caused in part by the destructive actions of capitalist greed and consumption. While Handmaids are still considered legitimate and therefore not put in the lowest class of society, if you fail to reproduce after three two-year assignments, you risk being demoted to being part of the “unwomen.”

Life as a Handmaid is brutal; you are limited in your rights and actions, you are forced to engage in sexual relationships, you lose all sense of self and identity and merely serve as a means to an end. And Offred, particularly, finds herself compromised: she’s assigned to a high-ranking member of the government who begins to treat her in ways outside of those that are customary of the Handmaid class. She’s allowed to read, given information about her daughter, and when she fails to get pregnant by the commander himself, his wife sets her up with the family driver, with whom Offred begins a more civilized relationship.

But as with most of the novel, nothing is as it seems and everything is dangerous. Offred is brought into the fold of the resistance—Mayday—by another handmaid, and while her lover seems to be part of that group as well, Offred’s last appearance comes as she’s being ushered into a van by a group that claims to be the resistance, and we are never privy to the final twist of her fate.

There is far more to the story than can be told in a couple paragraphs, but ultimately The Handmaid’s Tale is a timeless look at the importance of the rules which we live by, at the frightening possibilities of a world in which fanatics decide our fate. And that warning remains timeless: as we begin to question what we consider to be the underpinnings of society at large, it becomes even more crucial that we remember how hard-won the freedoms we have truly are. The second that we forget how important these lessons are, the second we open the door to speculative fiction becoming our new reality: and if nothing else, we should try our hardest to keep that door closed.