Love in the Time of Tear Gas: THE NIX’s Wild Literary Style Crashes Epically Against Its Vision of Our Diminishing Culture

The Nix obsesses over viewership. In its most powerful sequence, a dramatization of the riots that consumed Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, every action is mediated somehow: by screens, windows, radio waves, and news helicopters; by bird’s-eye-views both literal and figurative, hallucinations, clouds of tear gas–even the world as imagined through a drop of water by the consciousness of none other than a fictionalized Walter Cronkite.

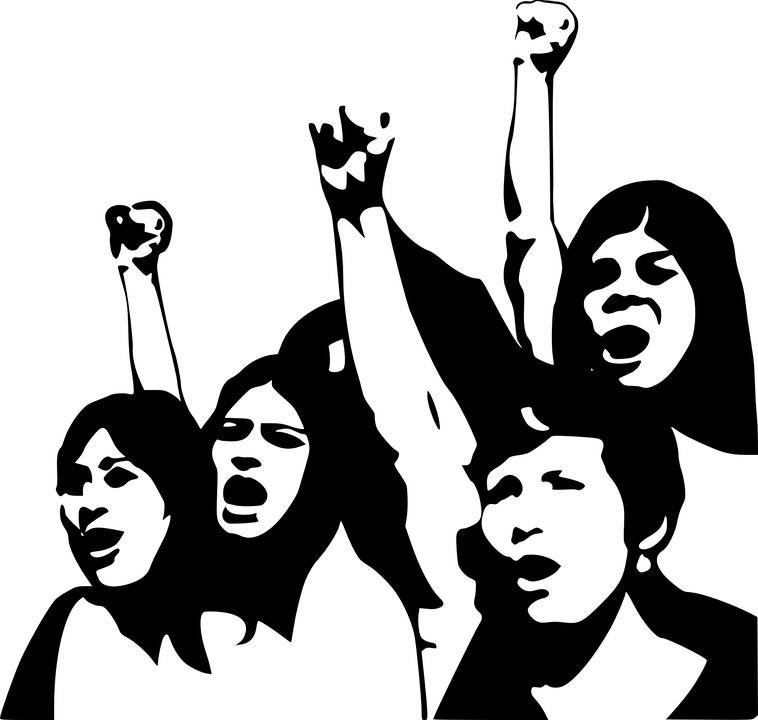

Author Nathan Hill is keenly aware of how these filters interfere with information, with their subjects, and their audience. The news transmits scenes of armed feminists to incredulous households in Iowa; shots from above reduce humans to flecks in a crowd; images selectively obscure events off camera or behind closed doors; the tear gas blinds and punishes, conceals exits, obscures its own suffering. In at least one instance, the screen itself is both confinement and weapon; the students are beaten against the leaded windows of a posh hotel, their suffering flattened to entertainment for the patrician delegates inside. But the window panes crack, then explode, and students and police spill bloodily together across the feet of their bemused audience. The significance of the breach comes to bear especially hard on one main character, who is critically wounded, his spine broken across the shattered boundary.

The dual responsibility and hazard of something as simple as showing people where to look weigh heavily, of course, on Walter Cronkite: “the danger of television is that people begin seeing the entire world through [a] single drop of water. How that one drop refracts the light becomes the whole picture.” Indeed, during the 1960s the media brought the world into people’s line of vision in an unprecedented way, galvanizing simultaneously demands for social progress and cries of reactionary resentment. It is clear that Hill is reflecting on his similar obligations as a novelist; but after finishing The Nix, I couldn’t shake the sense that this particular subgenre–the sprawling, polyphonic, time jumping, quasi-satire of American culture–has its own accreted conventions that have become obstacles to honest writing about political movements and social inequity.

But to cast The Nix as an intentionally “political novel” is a gross misrepresentation. At its heart, it’s about Samuel, a college professor, trying to understand his estranged mother, Faye, after she re-enters his life (and the public eye) when she’s arrested for assaulting a Republican presidential candidate. Samuel’s and Faye’s stories layer captivating vignettes from their lives, including tales of the lonely prodigy Bethany and her traumatized brother, Bishop, as well as a troubling video game addict known only by his screen name, Pwnage. Faye in particular is a wonderfully well-wrought character, whose life choices eventually settle into a cohesive pattern of painful, relatable contradiction. These are not stories that needed to be improved on or illuminated by their connections to the Iraq War and American culture writ large, but the siren songs of cultural relevance are hard to resist.

The most distinctive trait of novels like The Nix is the ensemble, and the guiding principle is a recognizably American one: the bigger, the better. These stories are praised for distinctness and abundance, and Hill’s debut strides proudly from Iowa to Chicago to New York to Norway, from the dawn of World War II through the 1968 riots at the Democratic National Convention, the Iraq War protests, and the birth of the Occupy movement.

Several of the supporting characters may be flat, but the interplay between the voices of hippies, housewives, police officers, and capitalists contribute to a literary style of vivid “bigness”. It is their very difference from one another that creates a portrait of personalities in opposition that are nevertheless stubbornly interconnected; an unblinking, ostensibly dispassionate vision of a culture. This is the coveted representationalism that has come to be recognized as a type of open-hearted social wisdom unique to novels like The Nix.

But this literary style was not built for true pluralism. The characters are types, and each stands alone. To showcase likeness or collectivity in a positive light would require repetition and similarity, the likes of which are literary weaknesses ambitious novels abhor. Cacophony demands individuation, and it has become an unspoken rule of such portraits of America that it also calls for false equivalence. Systems are reduced to their representatives; they are given inner monologues and backstories. The sins of power, built carefully over decades, are translated to personal failings: in a pivotal scene, a cop named Officer Brown beats students with pathological ferociousness because he was humiliated by a sexually liberated lesbian. Likewise, Samuel’s agent Guy Periwinkle, who literally looks down on Zuccotti Park from an office adorned with framed advertisements, is snide and callow, but he is also the whole of America’s cynical self-absorption transubstantiated into flesh and blood. He’s villainous, but through him an entire industry is placed on equal footing with the masses. His interactions with Samuel become uneasy parables for structural corruption because they are not at all to scale. In our real lives we are rarely, if ever, permitted to look such perpetrators in the face, or influence power in any discrete way.

In one of their final dialogues, Guy waxes philosophically on the troubles of the world, boiling it down to a personal choice between cynicism or idealism: conscience merely a matter of self-esteem. Protest is a leisure activity, a mode of personal expression taken up by people—some misinformed but well-intentioned, others clear-eyed and hence self-interested—united above all else by their lack of skin in the game.

The logic of this hyper-individuated literary style can’t help but lead to a politics that places blame on the citizen. Ideas like capitalism and globalization aren’t explored seriously in The Nix, but, tellingly, the word “consumerism” appears multiple times. American tragedy is repeatedly typified by the likes of video games, frozen dinners, students who don’t like to read Hamlet, an app called “iFeel,” and a fictional pop song titled “You Have Got To Represent.” These all things we could choose to avoid, or areas where we could stand to improve, if only we had the self-discipline.

One of The Nix’s most original and compelling characters, the gamer Pwnage, is a wreckage of such consumption: in his filthy apartment, the paradoxical ambitions of the novel to be at once Great and American collide furiously. His problems are culturally representative in that they are of his own making; the stage set of his tragedy is his own apartment; the punishment is wreaked, monstrously, on his body. It is to Hill’s tremendous credit that Pwnage is complicated and humanized, and his chapters are some of the novel’s most fascinating.

Literary convention accumulates, and artists must learn what to mimic as well as what to abandon: which myth, which rule must be thrown out to grow something new from rocky places where no one has ever been. The dilemma of the polyphonic, culturally diagnostic novel originates not in the individual, but the landscape of false equivalence, the aim for disinterest, the smear of the singular into empty universality. There is an American smugness in not having an opinion, or a politics, whose intensity has become downright lustful. There is nothing wrong with the individual—that is all we’ve ever had–as long as it is brave enough to present itself fully and honestly, and accept accountability. As long as it doesn’t erase itself into dispassion and pretend to omniscience and infallibility.

It is when this perspective is deleted that you find yourself in the awkward, self-reflexive position of having nothing to interrogate but the window, the news helicopter, the bird’s eye, the drop of water.